Borio, deflation and bank intermediation

Some time ago, I wrote that the BIS seemed to be on the dark side of macroeconomics. Earlier this month, Borio et al seemed to confirm this by publishing a quite fascinating paper titled The costs of deflations: a historical perspective. A number of economists, such as George Selgin or a number of market monetarists, had already pointed out the difference between good and bad deflation, which went against the mainstream view that deflation is always a bad thing. Borio and his team went even further.

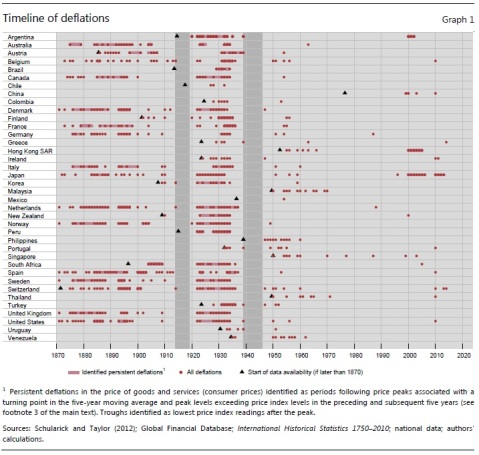

Analysing inflation data in a sample of 38 countries since 1870, they come to the remarkable conclusion that the link between deflation and low growth/recession is almost non-existent:

On balance, the relationship between changes in the consumer price index and output growth is episodic and weak. Higher inflation is consistently associated with higher growth only in the second half of the interwar period, which is dominated by the Great Depression – the coefficients are positive and statistically significant. At other times, no statistically significant link is apparent except in the postwar era, in which higher inflation actually coincides with lower output growth, with no significant change in the correlation during deflations. In other words, the only sign that price deflation coincides with lower output growth comes from the Great Depression and its immediate aftermath.

Their paper is a great data gathering exercise:

As we can see, many countries were used to experiencing long deflationary periods before the Great Depression. Surprisingly (for some), all deflationary periods actually coincided with rapid productivity growth and real income improvements. Long deflationary periods virtually disappeared after WW2 as the mainstream economic view started to associate deflation and depressions following the experience of the 1930s. While the authors do not find any correlation between deflation and slow economic growth, rerunning their regression only taking into account ‘persistent’ deflations (at least 5 years long) gave the same results: none, as long as the Great Depression is excluded (and very low if included).

However, Borio finds a strong relationship between asset price falls (house prices in particular) and decline in economic performance, both on annual and persistent bases, which seems to explain most decline in output throughout his sample period:

The results are rather striking. Once we control for persistent asset price deflations and country-specific average changes in growth rates over the sample periods, persistent goods and services (CPI) deflations do not appear to be linked in a statistically significant way with slower growth even in the interwar period. They are uniformly statistically insignificant except for the first post-peak year during the postwar era – where, however, deflation appears to usher in stronger output growth. By contrast, the link of both property and equity price deflations with output growth is always the expected one, and is consistently statistically significant.

To a bank analyst like me, this is expected. A general decline in prices of some asset classes affects banks in very specific ways. On-balance sheet, banks classify assets either as ‘held to maturity’ (HTM), ‘available for sales’ (AFS), or ‘fair valued/held for trading’ (FV). While asset price variations do not affect HTM assets, FV ones directly impact banks’ net income, and hence banks’ equity capital. AFS asset price fluctuations, on the other hand, do not affect bank’s profitability but indirectly impact banks’ capitalisation through ‘comprehensive’ income. As a result, a decline a in a number of asset prices can severely reduce banks’ capitalisation. For instance, Barclays said that

if the yields on 10-year Treasury bonds reverted back to their historical average it would wipe nearly a fifth off the tangible book value of European banks.

But falls in asset prices also affect banks through the collateral and off-balance sheet channels: they have to pledge more collateral to secure funding, limiting growth. As mortgages now represent most of banks’ assets, a general fall in property prices is the most problematic. Banks calculate the amount of provisions they need to put aside against their mortgage portfolio. In order to do this, they calculate borrowers’ probability of default (PD), their own exposure at the time of default (EAD), and the loss they would experience given an actual default (LGD). Mortgages are loans collateralised by property. The LGD component of the equation increases a lot when property prices collapse, even if the other variables remain stable.

For example, when a bank originates a 90% loan-to-value mortgage, the value of the loan remains below the value of the property (= collateral) as long as property prices don’t decline by more than 10%. (To which needs to be added legal/foreclosure/reselling costs) When property prices decline strongly enough, even if other economic factors are unaffected, banks have to increase their provisioning, which directly impacts their net income and, indeed, the strength of their capitalisation. The ability of banks to intermediate between depositors and borrowers becomes temporarily impaired, and other potential real economy borrowers suffer. As such, Borio’s results are unsurprising.

Moreover, the Basel regulatory framework seems to have amplified this phenomenon. As Borio says

And notably, the slowdown following property price peaks appears to be somewhat stronger in the postwar era.

Let’s recall this recent research, which highlighted that, due to government interference and regulation, real estate lending had become the main driver of bank’s lending growth in the post-WW2 era, to which I pointed out that most of this growth was due to changes introduced by Basel.

Those results strongly question the current central bank focus on inflation, and inflation targeting in general. While it sounds unreasonable to ask central banks to identify bubbles (they can’t), wide asset price fluctuations could be indicators that monetary policy is too ‘loose’. Remember that Wicksell defined the natural rate of interest as the rate that is neutral in respect to commodity prices. In the financial community, a growing number of investors and bankers are now warning of the potential consequences of what they view as overvalued prices (see here, here, here…).

However, the effect of monetary policy on asset prices has become harder to disentangle from Basel-only effects. How is monetary policy supposed to respond to regulatory-induced distortions? Even by trying to maintain a stable NGDP growth, another property bubble pop could severely affect the banking channel of the transmission mechanism and banks’ ability to finance the real economy.

Update: a 90% LTV loan means that the value of the loan is BELOW the property value, which is what I originally meant but wrote ‘above’ for some reason. This has been corrected. I thank Justin Merril for pointing that out.

PS: Borio’s paper also published the 2 following charts, which I reproduced below and added the introduction of Basel:

Trackbacks / Pingbacks