The Economist gets it wrong, again

About 10 days ago, The Economist published three articles on General Electric and mixing industrials with banking. Those articles follow GE’s decision to divest its banking business, GE Capital.

In its editorial (the follow-up article is available here), The Economist declares that:

GE shows why industrial firms should avoid owning big finance operations. Occasional successes such as Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway can combine insurance with hot dogs. But most manufacturers are even worse at managing financial risk than banks are—and they are harder to supervise. A blow-up at the finance arm can sink the entire company.

In another short article, the newspapers attempts to warn industrial CEOs not “to turn your firm into Goldman Sachs”:

The case for a split is clear. Managers are even worse at dealing with financial risk than bankers are. A blow-up in a firm’s financial arm can hurt its main business. And giving tycoons access to savers’ cash can lead them into all sorts of temptation.

Well, that’s not really true. What The Economist is describing is the situation in which a few large companies have been allowed to set up banking arms. This is indeed a situation to avoid as it limits entrants in the market and as a result gives an artificially high market share to those who could set up banking activities, which often transform into TBTF entities and put their parent company at risk if ever they fail. In the end, you end up with a few huge banks and a few very large banking arms owned by non-financial corporations. But this is not a free market outcome. The Economist is suggesting that we restrict banking to banks. It will not make the TBTF problem disappear but reinforce it.

We want the exact opposite of what The Economist is describing. We want every single company, every Google, Amazon, Apple or Walmart, to be able to set up a banking or finance arm if it wishes to, as long as it believes it can convince customers that it is able to provide a cheaper and more efficient alternative/product*. The more banks on the market the more likely market shares are going to be granular and the balance sheet of each entity limited in size. In turn, this competitive landscape would make the TBTF issue disappear and customers benefit. Finally, as each banking entity remains relatively small under competitive pressure, it is also less likely to endanger the financial health of its parent company (or of the whole banking system) if ever it collapses.

*And many of those companies are already entering the financial systems, in particular in the payment space, with some success.

ETFs and market efficiency – some evidence

A few weeks ago, I speculated that the rise of ETFs negatively impacted market efficiency. At that time I had not heard of any research that provided evidences to confirm or dismiss my fears. Not anymore.

A few articles (see here, here, here and here) have reported that a recent Goldman Sachs equity research piece (titled ETFs: The Rise of the Machines) found that ETFs had more influence than previously believed on share prices. I haven’t had access to this GS report, but here’s an extract from one of the articles:

Are exchange-traded funds an unseen force, like gravity, that help determine stock-price moves? New research suggests that the rise of ETFs may be complicating stock pickers’ chances of selecting winners or losers. That could make it even harder for stock-fund managers to outperform their benchmarks as assets in ETFs grow.

The $1.2 trillion in U.S. stock ETFs is having a much larger impact on the market than the fund industry claims, according to a recent report from Goldman Sachs. At issue: Heavy trading of index-tracking ETFs appears to be herding individual stocks up or down together, particularly in niche industries such as real estate and mining.

Goldman’s equity research team contends that increases in ETF trading appear to be tightening correlations, or the tendency for individual stocks and sectors to move up or down in lock step, regardless of a company’s fundamentals.

This was precisely my point in my previous post. But the extent of this ‘ETF distortion’ is hard to measure:

Comprehensive data aren’t available, but a study last year by the Investment Company Institute estimated that only 9% of ETF trades trigger buying or selling in individual stocks. Goldman, however, assumes the number is much higher, closer to 50% in some sectors.

As ETFs keep growing as an asset class, it is likely that those effects are going to be exacerbated. Perhaps we need even more activist investors to bring some balance back to the Force.

Research review (2/2): effectiveness of macro-prudential policies

A couple of days ago I said I had a second paper to review (yes I originally said ‘tomorrow’, but circumstances changed, sorry about that). This paper by McDonald was published last month by the BIS under the title When is macroprudential policy effective? (also available on SSRN here.) I didn’t find it very convincing.

The author runs correlations between the implementation of macro-prudential policy measures and when in the housing cycle those measures occur:

One of the aims of this paper is to determine if loosening measures are ineffective because they are often implemented during downturns. In particular, I examine whether tightening and loosening measures have the same effect once you control for where in the cycle changes are made.

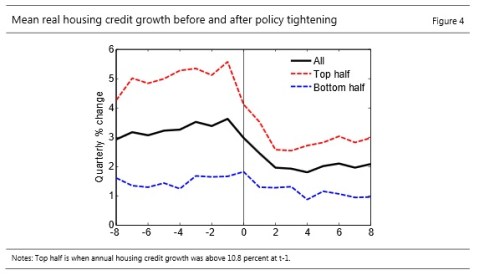

This is a laudable goal but the study doesn’t seem to actually do this. Indeed, the author concludes that (my emphasis):

The results suggest that tightening LTV and DTI limits tend to have bigger effects during booms. Several measures of the housing cycle correlate with the effects of changing LTV and DTI limits; annual housing credit growth and house-price-to-income ratios are some examples. Loosening LTV and DTI limits seems to stimulate lending by less than tightening constrains it. The difference between the effects of tightening and loosening is small in downturns though. This is consistent with loosening being found to have small effects because of where it occurs in the cycle.

This is not what I see from his dataset. It seems to me that, if house price to income ratios start falling after a macro-prudential tool is put in place, it is simply because the housing market is reaching its peak. Moreover, this effect only occurs from time to time. See the charts below. Red dots represent tightening macro-prudential measures. In the four housing markets considered, only a few red dots were followed by declining house price to income ratios. Many others were actually followed by…a house market boom. And the cyclical nature of the housing market does not seem to rely on an external regulator fixing macro-prudential thresholds. Prices fall by themselves…when they start getting too expensive.

Same thing for other markets (fewer data points though):

From those datasets it is clear that the correlation between tightened macropru ratios and constraining effects on housing markets is weak.

Even on aggregate, the author’s own chart doesn’t seem to match his claims:

A second study (The Use and Effectiveness of Macroprudential Policies: New Evidence) by Cerutti, Claessens and Laeven, published by the IMF last month as well, partly reflects what Aiyar, Calomiris and Wieladek had said in a past paper: macro-prudential policies leak. While both papers found some reduction in credit growth following the introduction of a macropru tool, they also noticed a tendency of market actors to take avoidance measures: the previous paper noticed a parallel growth in shadow banking, and the new IMF paper noticed increased cross-border lending growth.

Their conclusion clearly does not support regulators’ and central bankers’ hopes that macro-prudential policies could help offset the negative effects of low interest rates on some asset markets*:

We find that policies are generally associated with reductions in the growth rate in credit, with a weaker association in more developed and more financially open economies, and can have some impact on growth in house prices. We also show that using policies can be associated with relatively greater cross-border borrowing, suggesting countries face issues of avoidance. We do find evidence of some asymmetric impacts in that policies work better in the boom than in the bust phase of a financial cycle.

It seems to me that many researchers and regulators are currently trying to convince themselves that macro-prudential measures work. If only their own datasets could back up their (albeit moderate) conclusions.

* However, just following this quote, they do add that “taken together, the results suggest that macroprudential policies can have a significant effect on credit developments.” Which is pretty much the opposite of what they conclude from the data they process…

Research review (1/2): lending rates and monetary policy

I’ve been busy and away recently so not many updates. But I’ve also read quite a few recently published research papers on banking and thought I should mention two in particular, both by BIS researchers.

The first, by Illes, Lombardi and Mizen, titled Why did bank lending rates diverge from policy rates after the financial crisis, is directly reminiscent of my posts on banks’ margin compression due to the low interest rate environment. This paper is quite interesting, in particular for the data it gathered. But, it misses the main point.

Here are some of the charts they provide, which are very similar to my own, and clearly highlights how rates did not (actually could not) follow central banks’ base rates:

According to them:

There are three reasons why bank lending rates do not reflect the behaviour of policy rates in the post crisis period. First, the policy rate is a very short-term rate, while the lending rates to business and households normally reflect longer-term loans. The spread between the lending and policy rates therefore reflects the maturity risk premium alongside other factors that determine the transmission of policy to lending rates. Second, even if we correct for the maturity risk premium using an appropriately adjusted swap rate, the adjusted policy rate is not the marginal cost of funds for banks. Third, banks obtain funds from a variety of sources including retail deposits, senior unsecured or covered bond markets and the interbank market, and these differ in nature from policy rates since they comprise a range of liabilities of differing maturities and risk characteristics

This is very true but misses the fact that margin compression remains the main factor in the breakdown of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. However, they did come close to acknowledging this fact. They built a weighted average cost of liabilities (WACL), representing the funding cost of the banking system across all funding sources (deposits, secured/unsecured wholesale funding, central bank funding). Which provides some interesting breakdowns of European banks’ funding structure as you see below (and notice how central bank funding only represents a small share of liabilities):

They conclude that:

there is stronger evidence for a stable relationship between lending rate and the WACL measures we use to reflect funding costs of banks. We conclude that banks do not appear to have fundamentally changed their pricing behaviour in the post-crisis period even though bank lending surveys indicate that their credit standards have tightened since the financial crisis.

Banks’ demand deposits indeed reach the zero lower bound first, strongly reducing banks’ ability to further reduce their average costs of funds*. If lending rates had a strict relationship with funding costs, they would then stop falling at this point. Problem: a number of legacy variable rate loans (originated before rates started to fall) are calculated as central bank base rate + spread or LIBOR + spread, which continue to fall. This compresses banks’ margins, in turn endangering their profitability (you need to make revenues to pay for your non-interest operating costs…). Banks have no choice but to progressively increase the spread in variable rate loans (on new lending, and, if possible, on legacy lending). Risk premia (to cover for the cost of risk) and other factors as described by this paper are to be added on top of this compression phenomenon**.

They end their paper on a very appropriate question:

Further issues for research remain, including the question whether the effectiveness of the monetary policy transmission mechanism has been compromised by the breakdown in the relationship between policy rates and lending rates. Changes to policy rates may fulfil the Taylor principle, but retail rates may not adjust by a corresponding degree (see Kwapil and Sharler, 2010). This issue involves analysis of the relationships between policy rates, weighted average cost of liabilities and lending rates, as well as lending volumes, which we leave for further analysis

I’d add that actually, lowering the rates below a certain threshold harms banks and lending rather than helps…

Tomorrow I’ll review the second piece of research, on macro-prudential policy effectiveness.

*A fact acknowledged by this piece of research, even though they did not dig a little deeper into the accounting ramifications:

“In addition, deposit rates, which would normally be marked down along with the policy rates, have been constrained by the zero lower bound, which forced banks to reduce the mark-downs”

**To be clear, when funding cost does not fall as much as central bank’s base rates, it’s often the case that compression has been achieved (i.e. liabilities have reached the zero-lower bound, or close). When funding costs do fall (almost) as much as base rates, but the spread between lending rates and funding costs is widening, it often means that the risk premium is increasing (such as in Spain, Ireland or Italy).

Dimon on the next crisis (and fintech)

In a letter to shareholders last week, Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan’s CEO, makes a few interesting points and shows that he is aware of at least some of the tensions arising due from regulatory and fintech challenges.

He goes through a thought exercise to imagine what the next crisis might look like.

In my opinion, banks and their board of directors will be very reluctant to allow a liquidity coverage ratio below 100% – even if the regulators say it is okay. And, in particular, no bank will want to be the first institution to report a liquidity coverage ratio below 100% for fear of looking weak.

This is an excellent point, reminiscent of Bagehot’s teaching that artificial ratios and thresholds are set to trigger crises once they are violated.

In a crisis, weak banks lose deposits, while strong banks usually gain them. In 2008, JPMorgan Chase’s deposits went up more than $100 billion. It is unlikely that we would want to accept new deposits the next time around because they would be considered non-operating deposits (short term in nature) and would require valuable capital under both the supplementary leverage ratio and G-SIB.

In 19th century free banking systems in Scotland and Canada, healthy banks actively stepped in to protect the integrity of the whole banking system (which could at time be threatened when a single bank was going under). Regulation is now making this much more difficult.

In a crisis, everyone rushes into Treasuries to protect themselves. In the last crisis, many investors sold risky assets and added more than $2 trillion to their ownership of Treasuries (by buying Treasuries or government money market funds) […] But it seems to us that there is a greatly reduced supply of Treasuries to go around – in effect, there may be a shortage of all forms of good collateral […] banks hold $0.5 trillion, which, for the most part, they are required to hold due to liquidity requirements. Many people point out that the banks now hold $2.7 trillion in “excess” reserves at the Federal Reserve (JPMorgan Chase alone has more than $450 billion at the Fed). But in the new world, these reserves are not “excess” sources of liquidity at all, as they are required to maintain a bank’s liquidity coverage ratio.

This points reflects my arguments that the only effect of regulation has not been to make institutions more liquid but to silo what effectively becomes unusable liquidity. His point that excess reserves are required for the LCR is debatable though, as they could be replaced with other high-quality liquid assets (although bankers have reduced incentives to do so in an IOR and zero/negative interest rate world).

Changes in RWA and liquidity rules also particularly affect the ability of banks to extend credit and hence could increase pro-cyclicality according to Dimon:

In a crisis, clients also draw down revolvers […] – sometimes because they want to be conservative and have cash on hand and sometimes because they need the money. As clients draw down revolvers, risk-weighted assets go up, as will the capital needed to support the revolver. In addition, under the advanced Basel rules, we calculate that capital requirements can go up more than 15% because, in a crisis, assets are calculated to be even riskier. This certainly is very procyclical and would force banks to hoard capital. […]

In the last crisis, banks underwrote (for other banks) $110 billion of stock issuance through rights offerings. Banks might be reluctant to do this again because it utilizes precious capital and requires more liquidity.

Of course banks don’t literally ‘hoard’ capital (I can already hear Anat Admati from here). But what Dimon is saying is that banks would save up on scarce capital by preventing that sort of facilities from being used in the first place.

However, given what he described above, his claim that the banking system is “stronger than ever” feels quite odd.

Dimon also warns shareholders that further disruption is expected: Silicon Valley/fintech. While he says that “some payments systems, particularly the ACH system controlled by NACHA, cannot function in real time”, he points out that competitors such as Bitcoin and Paypal are coming in the payments area and that banks have to adapt to the real-time challenge. On top of that, quicker, more effective alternative lenders (read P2P and similar) are entering the market.

PS: I will however have to strongly disagree with Dimon’s claim that “America’s financial system still is the best the world has ever seen”…

Photo: Reuters/Keith Bedford

We now need PhDs in Bank Capitalisation

Banks’ capital structure is becoming ever messier and micromanaged by the day. Previous Basel iterations had already introduced Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 capital, leading to various types of regulatory capital ratios. The crisis demonstrated that only Tier 1 capital, as the most junior liability in a bank’s capital structure, was effective in absorbing losses. Basel’s capital requirements had effectively deceived investors, bankers, and financial markets in general.

Basel 3 decided to get rid of Tier 3 capital and changed the definitions of Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital, and introduced CET1 (core equity) becoming the most basic regulatory ratio available. CET1 was complemented by ‘Additional Tier 1’ (usually a form of perpetual deeply subordinated debt with discretionary coupon payments and equity-conversion features) and Tier 2 capital (often long-dated subordinated debt with no step-up or incentive to redeem) (see all details here).

Minimum capital ratios for all those capital ‘categories’ have also been defined or increased, and Basel had the idea of adding two extra capital buffers on top of that. The capital conversation buffer is a capital buffer made of…capital to protect the rest of the bank’s…capital. The concept sounds a little strange to say the least and its goal is to force banks to build up their capitalisation in good times so that they don’t breach regulatory minima in bad times. The idea is that banks should never ever breach those minima. Which made me question those statutory minimum requirements some time ago. What’s the point of having what is essentially ‘dead’ capital if one cannot use it to absorb losses without triggering a bankruptcy procedure? As a result it becomes necessary to add another buffer of capital to protect this ‘dead’ capital. You really couldn’t make that up.

On top of that, Basel also introduced a countercyclical capital buffer. This is a discretionary buffer of capital that banks need to raise or build up when regulators believe that the economy is overheating. How regulators will figure out that the economy is indeed overheating is anyone’s guess. But I believe that this ‘countercyclical’ buffer would actually be pro-cyclical in the presence of risk-weighted assets (and without applying certain macro-prudential tools): RWAs already incentivise banks to channel loanable funds to real estate borrowers. By raising capital requirements, real estate lending is likely to be the only remaining capital-efficient lending type. Which indeed would not slow down the growth of a housing bubble…

So that’s already quite a lot of rather opaque capital measures and instruments that regulators had devised, with unclear economic effects.

But that’s not it. Over the past few months regulators have been pushing for what is called TLAC (Total Loss Absorbing Capacity). TLAC requirements set that banks’ capital structure must comprise a minimum of ‘bail-inable’ debt equivalent to between 16 and 20% of RWAs. Europe is trying to implement those measures under the name MREL (Minimum Required Eligible Liabilities). This makes banks’ capital structure and balance sheet even less flexible. Despite boasting a very high CET1 ratio, the purest definition of regulatory capital, and a funding structure almost exclusively composed of deposits, a bank would still have to raise that sort of expensive hybrid capital (apparently bail-in-eligible unsecured long-term debt that would be junior to other senior creditors).

Evidently, those extra costs are going to be reflected in lending rates, which seems contradictory to the current monetary policy goal of reducing those same rates. Moreover, they are likely to exacerbate economic distortions as banks will intensify capital optimisation by picking the most capital-efficient sector to lend to (…real estate of course).

This is KPMG’s summary:

And that’s not it (you thought you were done, didn’t you?). As I described a few weeks ago (and here, as described by KPMG), regulators are now thinking of also adapting the RWA framework. While the newly-proposed risk-weights seem to be even more distortionary than the previous regime, Fitch, the rating agency, has come up with a rather embarrassing study. Basel wanted to replace RWAs’ reliance on credit ratings with ‘hard’ measures such as leverage. Fitch compared the proposed changes with the current approach and declared that:

The proposed use of balance sheet leverage is surprising given the more common use of cash-flow leverage metrics (e.g. debt/EBITDA) in corporate credit assessments, and leads to some surprising results. The new proposals would assign a number of highly-rated issuers to the highest risk buckets, and conversely, would have treated the majority (60%) of defaulted issuers in the Fitch portfolio as low risk (risk weighted below 100%). This indicates that the proposed metrics would fail to discriminate adequately between different credits.

Decrease in Rated Corporate Risk-Weights: Analysis of the Fitch-rated portfolio of global corporates indicates the proposals lead to a decline in average risk weights to 84% from 102% as compared to ratings based risk weights, with lower-rated corporates and cyclical sectors such as property and real-estate benefitting most. Risk weights for higher-rated corporates increased. However, the overall decrease would likely be offset by the proposed increased requirements for off balance sheet exposures. The overall impact will depend on the size and make-up of a bank’s portfolio, and the portion of corporate lending to rated entities.

Exposures to Banks

Missing Important Factors, Lack of Comparability: The BCBS proposes to determine risk weights for banks’ exposures to other banks based on the common equity Tier 1 (CET1) risk- based ratio and non-provisioned impaired exposures. In contrast, the current Basel framework provides two options, both ratings-based; the first based on the sovereign rating, and the other (more risk sensitive) based on banks’ issuer ratings. Fitch agrees that asset quality and capital ratios are important considerations in bank credit assessment. But these metrics on their own provide an incomplete basis for credit differentiation, as they omit important factors such as the bank’s operating environment (especially important for emerging-market banks), company profile, governance, liquidity and profitability. The proposed metrics also suffer from lack of comparability and consistency across jurisdictions (as reflected e.g. in the BCBS’s efforts to address consistency of risk-weighted assets, which underpin the CET1 ratio).

Ouch. While relying on credit ratings certainly isn’t perfect, it remains relatively close to a free market outcome in which specialised agencies would provide their assessment of borrowers’ creditworthiness to other market actors. But the proposed system makes it so much worse. As RWAs are the denominator of all regulatory capital ratios, this implies that those ratios essentially become meaningless (despite already being pretty flawed, we could nevertheless extract some information from them).

Banks’ capital structures are becoming opaque nightmares that introduce numerous distortions that have not been studied beforehand, despite the critical role of banking in our economy. A number of regulatory agencies are essentially playing Lego with various forms of capital layers. The complexity of capital regimes is such that it is time for universities to create PhD programmes in Bank Capitalisation*.

*This is a joke of course, although…

Absurd you said?

A bunch of new announcements over the past couple of weeks have made me wonder how far into absurdity our society is willing to go.

In Australia, the government announced a plan to tax all deposits up to A$250k in order to fund a deposit insurance scheme. While the 0.05% rate isn’t high, it remains a tax on savers, especially as interest rates are low. It’s going to make banks’ funding structure even more unstable, but nevermind. The implicit goal of the government is to convince depositors that there really is ex-ante funds to back their deposits (rather than an ex-post funding system, i.e. which finds the funds after a banking collapse), in order to avert any potential run. Reinforced moral hazard? Never heard of that.

Iceland came up with a proposal to end commercial banks’ ability to create money. I haven’t had a look into great details yet, but it looks like some sort of 100%-reserve banking system in which the money supply is controlled by the central bank while the government decides the allocation of the newly-created money. As Tim Worstall points out on the ASI blog, this proposal looks like a copy of Positive Money’s. Unfortunately, I had reviewed Positive Money’s book a few years ago after one of their members asked me to, and found both their proposal, and their economics, quite flawed. Anyway, as Tim says:

However, we’re absolutely delighted that someone undertakes the experiment. Actually, we’re delighted that someone else undertakes this experiment. Good luck to them say we. And we’ll come back in 20 years, see whether there’s been that abolition of boom and bust, been that persistent inflation or not, and then we can make a decision about whether to follow or not.

In the US, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has announced that it is proposing rules to force payday lenders to “make sure that….consumers can repay their loans.” So, despite nothing ever being risk-free in finance, payday lenders would only lend to risk-free customers, who possibly would have no issue getting a loan at normal bank….as they are ‘risk-free’. Mesmerising.

Finally, KPMG has published a new interesting report titled Evolving Banking Regulation (Part One). And what did KPMG find? Further changes in capital requirements are making banks’ balance sheet even more inflexible, and pushes banks away from deposits, despite regulators originally requiring banks to move away from non-deposit funding…:

Requiring systemically important banks to hold a minimum amount of ‘junior’ long-term liabilities that could be bailed-in ahead of ordinary senior creditors will leave many of these banks needing to raise additional debt that qualifies for inclusion, or at least to convert some existing long term debt into eligible debt instruments. This will add to the increasing cost and inflexibility imposed by regulation on banks’ balance sheets. Banks funded primarily by customer deposits (from individuals and corporates) may have to replace some of these deposits with long-term debt.

Moreover, they repeat what I had reported a few weeks ago: new RWAs plans are likely to accentuate credit market distortions:

These proposed new risk weights are generally higher on average than under the current standardised approach – in particular the proposed range of risk weights for corporates of 60–300 percent is considerably higher than the current range of 20–150 percent; while for exposures to other banks the range begins at 30 percent rather than the current 20 percent.

And they indeed agree with my assessment (my emphasis):

Wider economy implications as banks re-price and pull back from some activities. The move to risk drivers and more risk-sensitive risk weightings will accentuate the capital requirement cost to banks of exposures judged under the proposals to be at the riskier end of the spectrum. This could increase the cost – and reduce the availability – of bank finance and other services for these borrowers and other customers. The use of the proposed credit risk drivers will increase the capital cost of lending more than €1 million to small and medium enterprises (SMEs), lending against high LT V residential and commercial real estate, and lending to other banks with low capital ratios and poor asset quality.

PS: Some very good news nevertheless. George Selgin has a new blog called Alt-M, focused on alternative monetary systems. It replaces one of my favourite blogs, freebanking.org (which will apparently make a comeback under another form).

The real reason the Federal Reserve started paying interest on reserves (guest post by Justin Merrill)

I am fascinated by recent policies of interest on reserves, both positive and negative. I understand the argument for the People’s Bank of China paying interest on its deposits since they have a combination of a large balance sheet and high reserve ratios in order to control their exchange rate; their banks would go broke if 20% of their assets earned no income and their domestic inflation would run rampant if they didn’t curb lending. I also understand the logic for negative interest rates to stimulate the economies in Europe. I disagree with these policies, but there’s an internally coherent argument there. What hasn’t made sense to me is the Federal Reserve’s policy of paying interest on both required and excess reserves.

Why would the Fed simultaneously start the counterproductive policies of quantitative easing (QE) and interest on reserves (IOR)? Why would the Fed pursue the deflationary policy of IOR throughout the crisis when labor markets were weak and inflation was usually below their target? What if they could have achieved their policy goals as well or better by sticking to more traditional policies and not been stuck with such a large balance sheet and potential exit problem? My cynical intuition was that it was just a backdoor bailout to banks.

Determined to find the answer, I looked for statements and other sources from the Fed to find out the history of and justifications for IOR. What I finally found confirmed my suspicions and I think shows a big flaw in the Fed’s transparency and policy. What recently renewed my interest was Chair Janet Yellen’s Congressional testimony before the Senate in February, 2015. Senator Pat Toomey asked her about interest on reserves policy. Toomey used to be a bond trader, so he’s more financially savvy than most of his peers. I will summarize their dialogue about IOR but the video is available here and starts a little before one hour-seventeen minutes in: http://www.c-span.org/video/?324477-1/federal-reserve-chair-janet-yellen-testimony-monetary-policy

PT: In the past the Fed conducted monetary policy via Open Market Operations. You have said that you intend to raise the Fed Funds rate by increasing the interest paid on reserves. Since this will transfer money to big money center banks that would have gone to tax payers, why are you doing that instead of simply selling bonds? (emphasis added)

JY: We are paying banks a rate comparable with the market, so there is not a subsidy to banks. Our future contributions may decline when interest rates rise, but our contributions to the Treasury have been enormous in recent times.

Notice what she didn’t answer? The part of his question about why they are even using IOR at all!

According to the Fed’s Oct 6, 2008, press release:

The Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006 originally authorized the Federal Reserve to begin paying interest on balances held by or on behalf of depository institutions beginning October 1, 2011. The recently enacted Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 accelerated the effective date to October 1, 2008.

So we know the Fed was interested in using IOR as a tool prior to the crisis but weren’t in a hurry to do so until after the Lehman shock. The expedited authorization came from the TARP bill. So why were they interested in using it at all, and why did it become urgent and necessary in late September, 2008? The press release mentions “Paying interest on required reserve balances should essentially eliminate the opportunity cost of holding required reserves, promoting efficiency in the banking sector” and “Paying interest on excess balances should help to establish a lower bound on the federal funds rate. […] The payment of interest on excess reserves will permit the Federal Reserve to expand its balance sheet as necessary to provide the liquidity necessary to support financial stability while implementing the monetary policy that is appropriate in light of the System’s macroeconomic objectives of maximum employment and price stability.”

So paying interest on required reserves “promotes efficiency?” I think they are channeling Milton Friedman’s observation that reserve requirements are a tax on banks by forcing them to hold non-income earning assets. I’m not a fan of reserve requirements, and maybe it could be argued that they encourage disintermediation or alternative financing schemes that aren’t subject to the regulation, such as shadow banking, and that by paying IORR it offsets that. Fine, what I think is more interesting is the justification for interest on excess reserves. Why were they trying to provide liquidity without creating price inflation or overheating the labor market? Core CPI was below 2% at the time, PCE (an indicator the Fed looks at) was sharply negative, GDP numbers for the first two quarters were really weak and unemployment was trending up and was above 6% since August. There’s a lag to data, but in the October-early December timeframe we are focusing on here, they would have at least had August’s numbers.

Still not satisfied, I looked around at almost a dozen other Fed sources that tried to justify IOR. All of the sources said two or three things in particular: “Milton Friedman told us to pay interest on required reserves in 1959*, Marvin Goodfriend told us IOR could be used as a policy tool in 2002 and in 2008 we were having a hard time hitting our Fed Funds target.” I know hindsight is 20/20, but given the economic environment explained above, if you are providing liquidity and the economy is still stalling and you are missing your Fed Funds target on the low side, the problem is your target! You must REALLY trust your models to be so confident that a Fed Funds rate of two percent is worth defending in a liquidity crisis. I was about to chalk up the policy to mere incompetence and panicking in the fog of war when I came across this wonderful essay published by the Richmond Fed. It actually gives a fully honest account of what happened and why it was deemed urgent to start IOR:

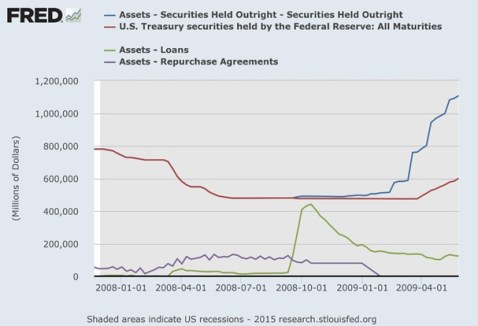

This feature became important once the Fed began injecting liquidity into financial markets starting in December 2007 to ease credit conditions. In making these injections, the Fed created money to extend loans to financial institutions. Those institutions provided as collateral securities from their portfolio that had, as a result of the financial market turmoil, become difficult to trade and value. This action essentially replaced illiquid assets in their portfolio with a credit to their account at the Fed, which would add reserves to the banking system. Adding reserves to the system will, under usual circumstances, exert downward pressure on the fed funds rate. At the time the Fed was not yet facing the zero-lower-bound on interest rates that it faces today. Thus, the injections had the potential to push the fed funds rate below its target, increasing the overall supply of credit to the economy beyond a level consistent with the Fed’s macroeconomic policy goals, particularly concerning price stability. To avoid this outcome, the Fed “sterilized” the effect of liquidity injections on the overall economy: It sold an equal amount in Treasury securities from its own account to banks. Sterilization offset the injections’ effect on the monetary base and therefore the overall supply of credit, keeping the total supply of reserves largely unchanged and the fed funds rate at its target. Sterilization reduced the amount in Treasury securities that the Fed held on its balance sheet by roughly 40 percent in a year’s time, from over $790 billion in July 2007 to just under $480 billion by June 2008. However, following the failure of Lehman Brothers and the rescue of American International Group in September 2008, credit market dislocations intensified and lending through the Fed’s new lending facilities ballooned. The Fed no longer held enough Treasury securities to sterilize the lending.

This led the Fed to request authority to accelerate implementation of the IOR policy that had been approved in 2006. Once banks began earning interest on the excess reserves they held, they would be more willing to hold on to excess reserves instead of attempting to purge them from their balance sheets via loans made in the fed funds market, which would drive the fed funds rate below the Fed’s target for that rate. When the Fed stopped sterilizing its liquidity injections, the monetary base (which is comprised of total reserves in the banking system plus currency in circulation) ballooned in line with Fed lending, from about $847 billion in August 2008 to almost $2 trillion by October 2009. However, this did not result in a proportional increase in the overall money supply. This result is likely due largely to an undesirable lending environment: Banks likely found it more desirable to hold excess reserves in their accounts at the Fed, earning the IOR rate with zero risk, given that there were few attractive lending opportunities. That the liquidity injections did not result in a proportional increase in the money supply may also be due to banks’ increased demand to hold liquid reserves (as opposed to individually lending those excess reserves out) in the wake of the financial crisis.

So the truth is that when the subprime mortgage crisis blew-up in December, 2007 the Fed started SELLING hundreds of billions in treasuries to sterilize their credit facility that engaged in repo of MBS. Since this did not provide aggregate liquidity, this was not a lender of last resort function, this was a credit policy to support MBS. Then after Bear Stearns failed in March, 2008 the Fed sold more treasuries to make billions in direct loans to firms such as Bear (to aid in their purchase by JP Morgan) and AIG. At their peak, during the Lehman shock, their direct lending totaled well over $400 billion, or about half their balance sheet.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=16fS

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=16fS

The damning truth is the Fed felt the urgent need to institute IOR because they were running low on treasuries but wanted to provide more liquidity. They were afraid to initially expand their balance sheet because in October, 2008 they were still concerned about inflation! Talk about missing the mark. They were concerned because the Fed Funds rate was below their target and they couldn’t control it. What they don’t seem to realize is that the Fed Funds is a barometer of liquidity. You don’t make the weather warmer by tricking your thermometer into not going below 70 degrees. I suspect it is the “Neo-Wicksellians” like Michael Woodford who took the money out of Wicksell who are to blame for this. This is a perfect example of Goodhart’s Law: “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” You can see in the chart below they tried, and failed, to create an interest rate channel by initially pegging the interest on excess reserves lower than the target rate. Eventually they gave up and harmonized all the rates at 25 bps. The effective Fed Funds remained below that because some institutions, such as the GSEs, have access to the Fed Funds market but not deposits at the Fed. This means there’s an arbitrage opportunity for banks to borrow on the Fed Funds market and deposit at the Fed. Since GSEs were nationalized, this might be considered another public subsidy. Either way, the primary dealer model and other differential treatment of institutions is broken.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=16fY

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=16fY

We no longer have the initial conditions that justified interest on reserves. We are not above the ZLB and fearing inflation while wanting to increase the balance sheet. We are in the exact opposite. The Fed should normalize, including abandoning IOR. This is Bernanke’s legacy. The same man who promised, “We won’t do it again” got so caught up in the act of directing credit, experimenting with new tools and obeying his models that he forgot to listen to Bagehot’s advice or even professor Bernanke’s.

*Friedman, Milton. 1959. A Program for Monetary Stability.

On the maximisation of shareholder value

This isn’t a post specifically about banking and finance, for once. A few days ago, this Economist’s Schumpeter column reminded me how misunderstood the ‘maximisation of shareholder value’ concept was. Milton Friedman’s famous principle that corporations’ only social responsibility was to maximise shareholder value (see his original article here) has been taken out of context and crucified as an inhuman example of corporate raider short-termism. I still remember my university corporate governance classes, showing us a chart depicting a corporate governance spectrum with ‘financial markets’ (aka Friedman) on one side and CSR on the other.

In a world of rule of law and property rights, there is no question that Friedman was right. Shareholders own the firm and put managers in charge of a strict and defined mission. This is a contractual agreement. When managers decide to deviate from their mission for broader ‘social’ purposes, they violate property rights and the terms of their contract.

But this is not where the misunderstanding lies. The misunderstanding is about short-termism. Maximising shareholder value does not imply maximising profits in the short-term. In reality, it is pretty much the opposite. People who believe that it is sufficient to target short-term results in order to boost the value of a firm are making a grave economic and financial error.

What maximises current shareholder value is the expectation that the firm is going to perform (increasingly) well in the future. Here, ‘future’ is not defined as the next quarterly, or even yearly, results. ‘Future’, here, in the absence of market-wide distortions, is long-term.

Let me explain. Investors, like everyone, are subject to time preference. As the future is uncertain, they value more highly present goods over future goods. As such, they discount future purchasing power according to their own time preference. This implies that the present value of a company’s share price is determined by the discounted expected future free cash flows generated by this company. And most of those cash flows (like 70 or 80%) reside in what we call the ‘terminal value’. This value is the aggregate of ‘all’ cash flows expected beyond a 5 or 10-year horizon.

Now let’s imagine that management has the opportunity to report great quarterly results at the expense of longer-term performance. Does beating market expectations necessarily mean that the share price will jump? No. If investors believe that management‘s actions have jeopardised longer-term performance, the share price will eventually decline*. Think about it: the coming period cash flow will be maximised, but the cash flows of the following periods, including those of the terminal value, will suffer. This evidently cannot qualify as ‘maximising shareholder value’.

Therefore, accusing the ‘maximisation of shareholder value’ concept of short-termism negates both finance theory and the power of expectations. When investors are confident in a company’s ability to generate long-term growth, they have no issue whatsoever in accepting lower short-term cash returns (i.e. dividend/share buybacks…), which usually translates into higher short-term (unrealised) capital gains. As The Economist points out:

far from being slaves to the share price, as progressives imagine, most companies are engaged in a constant process of negotiation between managers and investors over their strategy and time horizons. Mature companies such as Shell, Intel and Nestlé often invest for the long term without a squeak from fund managers. New-economy companies such as Google, Facebook and, particularly, Amazon have had no difficulty in persuading investors to sacrifice short-term returns (and indeed any control whatsoever) in return for long-term rewards.

Indeed, I have already pointed out that fears that activist hedge funds could dismantle healthy companies, or make ‘a quick buck at the expense of long-term performance’ was largely unfounded, and unlikely to happen in the vast majority of cases: “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time”.

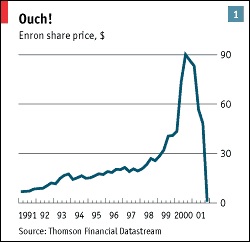

Now, some would argue that management could maximise shareholder value by engaging in ‘anti-social’ behaviour (from fraud to pollution…), which could positively affect performance/free cash flows in the long-term. In a market free of political or regulatory interference, this line of reasoning can only be valid in the short-term, as long as managers succeed in hiding their activities. However, when the news come out, investors are extremely likely to downgrade their expectations of future cash flows as they factor in reputational damage (i.e. loss of customers and/or suppliers) as well as litigation risks. By engaging in anti-stakeholders, fraudulent or ‘anti-social’ activities, managers have not been maximising shareholder value.

Unlike what The Economist says (“several companies that proudly practised shareholder-value maximisation went up in flames: Enron, Arthur Andersen and WorldCom, among others”), Enron did obviously not maximise shareholder value as it fell to… zero. It managed to get away with the illusion of performance as long as its fraud remained hidden. Once again, this is not what maximising shareholder value means.

*Perhaps not on announcement day, but as soon as a deeper analysis of the managers’ decision has been made.

Recent Comments