Some news + MMT and endogenous money

I know I haven’t posted in a long while, but I thought I’d give some news. And no it’s not an April fools’!

Work and personal matters have taken much of my time and left me unable to allocate time to blogging so my only ‘efforts’ have been on Twitter.

MMT revived the econ scene recently, which has led to my old endogenous money posts resurfacing. The Cato Institute finance and monetary blog Alt-M recently republished one and linked to others.

I also thought this post was the right time to show some practical evidence that banks do require funding to lend. As a comment on my old post on Alt-M says, a bank branch employee does not have to deal with funding requirements before lending. This would be a practical nightmare given the number of clients that deposit, withdraw and borrow small amounts. And indeed, retail banks’ funding is managed on a macro/aggregate level from the head office.

Things are however quite different in the case of corporate banks, as much larger amounts are involved. A typical example would be an RCF (i.e. revolving credit facility), which allows a large corporation to withdraw ‘on demand’ any amount it requires within the limits set by its loan agreement.

Most, if not all, revolvers comprise a timetable in their appendix that specifies how long before drawing on the facility the borrower needs to warn the treasury and operations department of the bank (or the agent in the case of a syndicate of banks) through a ‘utilisation request’. This is needed to allow the treasury to make sure they can fund the drawdown and prevent the bank running out of liquidity. And this is a direct real life counter-example to endogenous money theory.

See a publicly available example here. The utilisation request form is on page 154 and the timetable (reproduced below) is on page 172. Note how any drawdown requires the borrower to send an utilisation request one to three days before the effective drawdown. Any drawdown request occurring later than this deadline can be legally refused by the bank’s operation and treasury teams as they might not be able to secure, and then deliver, the funds.

Again, this is something that corporate bankers know, and that a number of academics seem to ignore.

____

In other news, Reuters report that the EU “approved new rules to lower capital requirements for insurers’ investments in corporate equity and debt” in order to “facilitate investment in small and medium-sized companies and provide long-term funding to the EU economy”.

This is again another example of policymakers demonstrating their clear understanding that banks (and insurers) capital requirements significantly affect the investment choice that they make. They definitely cannot pretend any longer that Basel rules had no effect on the mortgage boom of the past three decades…

____

That’s it for today. I’m not sure when I’ll be able to blog again. Could be next week, could be in six month time. I’d really like to blog more however, believe me.

The era of ‘soft’ central planning

More than a decade ago, The Economist (at the time still a classical liberal publication – how times change…) published an excellent article on ‘soft paternalism’:

But a new breed of policy wonk is having second thoughts. On some of the biggest decisions in their lives, people succumb to inertia, ignorance or irresolution. Their private failings – obesity, smoking, boozing, profligacy – are now big political questions. And the wonks think they have an ingenious answer – a guiding but not illiberal state.

What they propose is “soft paternalism”. Thanks to years of patient observation of people’s behaviour, they have come to understand your weaknesses and blindspots better than you might know them yourself. Now they hope to turn them to your advantage. They are paternalists, because they want to help you make the choices you would make for yourself – if only you had the strength of will and the sharpness of mind. But unlike “hard” paternalists, who ban some things and mandate others, the softer kind aim only to skew your decisions, without infringing greatly on your freedom of choice. Technocrats, itching to perfect society, find it irresistible.

A decade later, recent announcements and publications have made it increasingly clear that we are headed for ‘soft’ economic planning. The extract from The Economist above almost perfectly suits policymakers’ current view of the financial system. They now intend to use the existing banking regulatory framework to influence banks’ behaviour (or help them make the ‘right’ decision as The Economist of yesteryear would put it) and micromanage various economic parameters, in order to finally achieve the ‘stable’ and ‘sustainable’ society their mathematical models (or political visions) describe.

It should not come as a surprise: since the financial crisis, regulators have been speaking of using their discretionary powers to tweak rules and regulations to provide (dis)incentives and achieve specific targets. As I reported in a previous post, the European Commission declared last December that it “could lower capital requirements for environmentally-friendly investments by banks in a bid to boost the green economy and counter climate change.” The reception of this idea by regulatory bodies has been rather cold, let’s be honest. But now it looks like they are warming up to the idea and preparing the ground for similar regulatory announcements.

Indeed, a couple of weeks ago, the BIS published a new research paper adequately titled Towards a sectoral application of the countercyclical buffer: a literature review.

The main message of this paper is that, despite their largely untested nature and ‘scarce’ or ‘mixed’ empirical evidence, the literature ‘shows’ that there is a ‘justified need’ for the application of sectoral macroprudential tools. One can wonder how the authors of this paper managed to link the terms ‘scarce/mixed empirical evidence’ and ‘shows’.

I haven’t had the occasion to review all the paper referred to in this document but, as it is the case with most papers covering macroprudential regulation, those are likely to downplay the negative effects of such policies and overstate their benefits.

And indeed, a quick look at a couple of references shows that even most of the limited empirical evidence listed as ‘succesful’ by the BIS do not actually qualify as solid research or contain serious caveats:

- A Bank of England publication referring to the ‘effective’ implementation of sectoral macropru in Australia despite not providing any evidence of this claim and only referencing an Australian regulatory paper published…before the implementation of that very measure.

- Another BIS research piece reporting the positive effects of sectoral macropru on consumer and credit card loans in Turkey despite offering absolutely no robust statistical analysis, based on a sample of n = 2, and whose effects were most probably confounded by the sharp increase in reserve requirements that occurred at the same time.

- A paper that shows some pricing and volume effects of an increase of risk-weighted assets on certain auto loan LTV and maturities in Brazil but also shows a rebalancing, or ‘leak’, towards other maturities (and coincidentally providing some empirical evidence to my theory of credit misallocation through RWA differential).

But providing solid empirical and theoretical foundations was not the purpose of this paper; providing central bankers and policymakers with some sort of ‘research’ justifying the use of economic management tools was. (on a side note, in my experience most economic commenters seem to focus on abstracts and are unwilling to dig into the research papers they refer to, often reporting widely exaggerated results – a recent meta-analysis confirmed this impression, finding that “nearly 80% of the reported effects in these empirical economics literatures are exaggerated”, also see this presentation)

In reality, sectoral macroprudential policies suffer from the same flaws as general macroprudential policies, that is: there is little to no solid evidence of effectiveness, it cannot counteract monetary policy, it assumes away Public Choice and Hayekian knowledge dispersion issues (see here for a full critique of macroprudential policies). Sectoral macropru merely pushes this reasoning further: not only is it assumed that policymakers have the ability to spot and correct macroeconomic variables and imbalances in real time, but also that their macroeconomic omniscience allows them to do so on a sector per sector basis.

Worse, sectoral macropru also opens the door to interest groups and lobbying, which could result in politicians tweaking bank capital requirements to benefit (or penalise) specific industrial sectors. The European Commission proposal outlined above is a typical example of this (benefiting ‘environmentally-friendly’ industries – who gets to decide what firm is ‘environmentally-friendly’?). Or recently, Banque of France governor Francois de Villeroy de Galhau suggested instead (gated link) to “make it harder for banks to maintain exposure to industries perceived as contributing to climate change.” This is another example of sectoral macropru application, negative this time.

Just a few days ago, French president Macron rightly declared that “we have very strict bank rules with the result that banks lend less and less to small and medium sized companies.” This is a welcome admission by a top policymaker that Basel rules have distorted the allocation of credit and penalised smaller firms for no valid reason. Yet Macron falls into the same discretionary micromanagement trap: he then adds that governments could “modulate these rules for banks and insurance companies depending on the reality of the country and the economic cycle and that, when an economy recovers, we could guide banks’ targets – and that could be done by finance ministers and not only accounting and technical rules” (my emphasis).

This fits The Economist’s decade old description of soft paternalism marvellously. The state and its bureaucrats will subtly ‘guide’ banks’ targets, enlightening society. Unless their goal is the following election – though am I too cynical? In any case those bureaucrats will sooner or later find out that, for an economy to flourish, rules beat discretion hands down.

Another way central bankers can influence the allocation of capital in the economy is through stress-testing. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, recently suggested the introduction of ‘carbon stress tests’. Those stress tests would obviously be designed to force the financial industry away from carbon-heavy industrial sectors. Is it a matter of time before ‘sugar stress tests’ or ‘alcohol stress tests’ are also unveiled?

Despite its numerous theoretical and empirical defeats, central planning keeps coming back under a form or another, armed with new (flawed) tools, often to satisfy the naïve targets of idealists, sometimes to satisfy the thirst for power of autocrats. Such a commitment to a misconceived idea is admirable. And dangerous. When will it finally die?

PS: Leland Yeager, one of my favourite economists (see this old post of mine in which I discussed some of his ideas), passed away a few days ago. He will be missed.

PPS: George Selgin and Bob Murphy debated fractional reserve banking here.

Picture credit: The Economist

‘Sovereign money’: a bad idea, part deux

Last week, right after I wrote my previous post on ‘sovereign money’, the BIS published a whole report on this very concept (and more precisely, on the idea of using cryptocurrencies or blockchain-based systems to give anyone the ability to deposit cash/hold assets at the central bank). It is a very good report. Do read the whole thing.

The BIS differentiates between wholesale digital currencies, primarily used for clearing and settlement and available to financial market participants, and ‘general purpose’ ones, which allow the general public to effectively ‘acquire’ digital cash at the central bank rather than hold deposits at a commercial bank or hold central bank physical cash. The BIS acknowledges that this could have some repercussions on the conduct of monetary policy and of its transmission mechanism (as such digital currency would become a potentially widely-held asset and a liability on the central bank’s balance sheet).

The report is pretty detailed about the potential benefits and issues of such digital sovereign money (from minor Know-Your-Customer issues to more critical cross-border deposit flows and siloed high-quality collateral), and essentially agrees with and elaborates on many of Jordan’s – and my – arguments. But crucially (and this is the main focus of this post), it also looks at what could happened should a full-on financial crisis strike. In my previous post, one of my main concerns was commercial banks’ funding depletion due to deposits ‘leaking’ towards that new low risk, very liquid and convenient, central bank legal tender (Tolle, in a BoE blog post, went as far as saying that this could end fractional reserve banking). The BIS takes this reasonning further, pointing at the worsening impacts of such instruments on financial instability risk:

A general purpose CBDC could give rise to higher instability of commercial bank deposit funding. Even if designed primarily with payment purposes in mind, in periods of stress a flight towards the central bank may occur on a fast and large scale, challenging commercial banks and the central bank to manage such situations.

Digital sovereign money would therefore facilitate bank runs, which could occur with “unprecedented speed and scale”, and increase the probability and severity of a crisis. Of course, as history teaches us, in such situation regulators would probably blame ‘inherently unstable’ banks – or capitalism – for not holding enough liquidity and not having a stable-enough deposit base in the first place. Which would be another opportunity to further regulate banks and grant regulators more power. But that’s another story.

Another very interesting point raised by the BIS, and which was also present among my top concerns, is political interference and less effective capital allocation. While the BIS doesn’t elaborate much on political interference in its piece, it does acknoledge the limitations of central planning (and even refers to Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society!):

Introducing a CBDC could result in a wider presence of central banks in financial systems. This, in turn, could mean a greater role for central banks in allocating economic resources, which could entail overall economic losses should such entities be less efficient than the private sector in allocating resources. It could move central banks into uncharted territory and could also lead to greater political interference.

It looks like, for once, many leading central bankers, the central banks’ central bank (i.e. the BIS) and I are on the same line. Champagne?

‘Sovereign money’: a bad idea

Commenter Intajake recently asked what I thought of some BoE research aiming at allowing the general public to hold accounts directly at the central bank. While in this particular case the BoE is considering the use of a crypto-currency/blockchain-type structure to facilitate the implementation of such a system, it’s definitely not a new idea. A number of activists have been advocating a nationalised system of current accounts for decades; more recently, Positive Money has been very vocal in defending ‘transaction accounts’ of ‘risk-free sovereign money’ held by the central bank (see their paper here; which, while not mentioning blockchain, sounds remarkably similar to the BoE “central bank digital currency” initiative).

Coincidentally, Thomas Jordan, Chairman of the Swiss National Bank, also commented on the matter in a speech in January. This follows a campaign for the introduction of sovereign money which led to the organisation of a referendum in the country (next June). Despite this campaign calling for more power to be granted to the SNB, it is interesting to see that Jordan, and the SNB in general, rejects the idea and mostly sees drawbacks to it.

Essentially, Thomas’ rejection of the initiative revolved around six main points:

- Political interference would have negative effects on the lending function of the SNB, which would now be centralised:

With the introduction of sovereign money, the SNB would be landed with a difficult role in lending. The initiative calls for the SNB to guarantee the supply of credit to the economy by financial services providers. In order to carry out this additional mandate, the SNB could provide banks with credit, probably against securitised loans. Depending on the circumstances, the SNB would have to accept credit risks onto its balance sheet and, in return, would have a more direct influence on lending. Such centralisation is not desirable. The smooth functioning of the economy would be hampered by political interference, false incentives and a lack of competition in banking.

- Sovereign money would restrict the supply of credit as the deposit creation function of banks disappears:

Second, sovereign money limits liquidity and maturity transformation as banks would no longer be able to create deposits through lending. Sovereign money thus restricts the supply of liquidity and credit to households and companies. The financing of investment in equipment and housing would likely become more expensive.

- Financial stability would not improve as investors and borrowers will keep making mistakes:

Investors and borrowers will always make misjudgements. A switch to sovereign money would thus not prevent harmful excesses in lending or in the valuation of stocks, bonds or real estate. Also, while the sovereign money initiative targets traditional commercial banks, let us not forget the role played by ‘shadow banks’ in the global financial crisis of 2008/2009.

- Sovereign money requires money supply management, which is in contradiction with SNB’s current inflation targeting mandate.

- Money supply management and inflation targeting both involve ability to reduce the money supply when necessary, usually through open-market operations. However, it is unclear how this process would work in a ‘debt-free’ sovereign money framework.

- The acceptance of the initiative would plunge the Swiss economy into extreme uncertainty.

I believe Jordan makes some very good points, and I’m particularly sympathetic to numbers 1, 2 and 5. The centralisation of the lending function in an institution subject to political power is what worries me most.

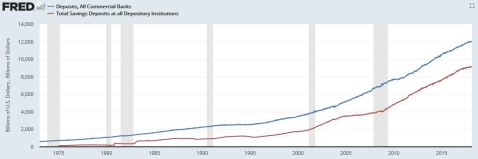

As saving deposits represent the largest type of deposits in the US (76%, if my reading of FRED is correct, see below) and possibly in Europe (I can’t find similar data), one could argue that sovereign money current accounts would only impact banks modestly. I believe there is more than meet the eye here.

First, savings have considerably grown as share of total deposits over the past two decades, possibly as a result of QE; in the couple of decades before the crisis they represented a more modest 40 to 60% of total deposits. Second, in the era of near-zero interest rates, a number of savers would probably think that the rewards of keeping their savings at ‘risky’ commercial banks is not worth the risk and instead transfer their savings to the central bank. After all, a large share of saving deposits is actually available on demand and the difference between a 0 and 0.25% remuneration rate is rather minimal. Moreover, saving deposits represent the largest share of non-wholesale funding for the banking system mostly due to the large number of small saving banks in the economy, many of which are specialised in non-productive mortgage lending, and which provide a number of more remunerative long-term time deposit products.

The larger banks, which have larger corporate lending books, rely more on demand deposits/current accounts for funding. Those banks are often the only institutions able to provide financing on a bilateral or syndicated basis to the largest of businesses, which are also the most politicised of companies. A very quick look at the latest financial statements of some of the world largest banks shows: HSBC Bank reported 86% of deposits available on demand, Deutsche Bank 61%, BNP Paribas 78%; JPMorgan reported 39% of total ‘transaction’ accounts and only 4% of time deposits and Wells Fargo 32% and 7% respectively; Mizuho reported 58% of demand deposits.

As those banks’ funding sources start dwindling, banks will have no choice but to turn towards their central bank for funding. As the central bank becomes the main funding provider of the banking system, it also starts having a say in regards to the allocation of credit in the economy, in particular when it involves politicised multinational corporations; lending competition becomes suppressed.

It is quite worrying that sovereign money activists have still not incorporated any element of Public Choice theory – or merely economic history – into their framework and don’t realise the dangers of having the state almost fully in control of the allocation of the money supply.

What the world needs is more competition in banking, not less. Instead of supporting the centralisation of deposit-taking and lending, those activists should instead support the new challenger banks and other fintech startups that are currently emerging. Many of those recently started taking deposits through new current account offerings and such ‘sovereign money’ initiatives would simply kill them off. Be careful what you wish for.

The money multiplier is alive

Remember, just a few years ago when a number of economic bloggers tried to assure us, based on some misunderstandings, that banks didn’t lend out reserves and that the ‘money multiplier was dead’?

I wrote several posts explaining why those views were wrong, from debunking endogenous money theory, to highlighting that a low multiplier did not imply that it, and the basis of fractional reserve theory, was ‘dead’.

Even within the economic community that still believed in the money multiplier, there were highly unrealistic (and pessimistic) expectations: high (if not hyper) inflation would strike within a few years we were being told, as the first round of quantitative easing was announced. Of course those views were also wrong: the banking system cannot immediately adjust to a large injection of reserves; even absent interest on excess reserves, it takes decades for new reserves to expand the money supply as lending opportunities are limited at a given point in time.

A few years later, it is time for those claims to face scrutiny. So let’s take a look at what really happened to the US banking system.

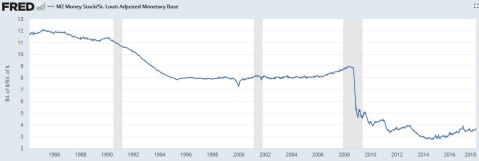

This is the M2 multiplier:

As already pointed out several years ago, the multiplier is low; much lower than it used to be between 1980 and 2009. But it is not unusual and this pattern already happened during the Great Depression. See below:

Similarly to the post-Depression years, the multiplier is now increasing again.

Let’s zoom in:

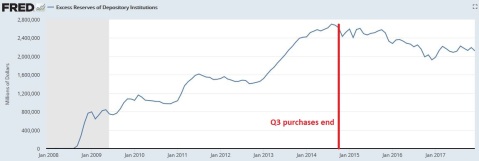

Since the end of QE3, the M2 multiplier in the US has increased from 2.9 to 3.7 in barely more than three years. This actually represents a much faster expansion than that followed the Great Depression: between 1940 and 1950, it increased from 2.5 to 3.5, and from 1950 to 1960, it increased from 3.5 to 4.2.

Unsurprisingly, this increase occurred as excess reserves finally started to decline sustainably:

As we all know, following the 1950s, the multiplier eventually went on increasing for a couple more decades, reaching highs during the stagflation of the 1970s and early 1980s. Unless a new major crisis strikes, it is likely that our multiplier will follow the same trajectory, although I am a little worried about the rapid pace at which it is currently increasing. One thing is certain: the money multiplier is alive and well.

A boring story of critical Basel risk-weight differentials

After years of negotiations, international banking regulators have finally come up with an apparent finalisation of Basel 3 standards. Warning: this post is going to be quite technical, and clearly not as exciting as topics such as monetary policy. But in order to understand the fundamental weaknesses of the banking system, it is critical to understand the details of its inner mechanical structure. This is where the Devil is, as they say.

The main, and potentially worrying, evolution of the standards is the

aggregate output floor, which will ensure that banks’ risk-weighted assets (RWAs) generated by internal models are no lower than 72.5% of RWAs as calculated by the Basel III framework’s standardised approaches. Banks will also be required to disclose their RWAs based on these standardised approaches.

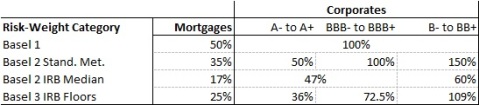

What does this imply in practice? A while ago, I described the various methods under which banks were allowed to calculate their ‘risk-weighted assets’, which represent the denominator in their regulatory capitalisation formula:

Banks can calculate the risk-weighs they apply to their assets based on a few different methodologies since the introduction of Basel 2 in the years prior to the crisis. Under the ‘Standardised Method’ (which is similar to Basel 1), risk-weights are defined by regulation. Under the ‘Internal Rating Based’ method, banks can calculate their risk-weights based on internal model calculations. Under IRB, models estimate probability of default (PD), loss given default (LGD), and exposure at default (EAD). IRB is subdivided between Foundation IRB (banks only estimate PD while the two other parameters are provided by regulators) and Advanced IRB (banks use their own estimate of those three parameters). Typically, small banks use the Standardised Method, medium-sized banks F-IRB and large banks A-IRB. Basel 2 wasn’t implemented in the US before the crisis and was only progressively implemented in Europe in the few years preceding the crisis.

While Basel 3 did not make any significant change to those methods, at least in the case of credit risk, regulators have argued for years about the possibility of tightening the flexibility given to banks under IRB.

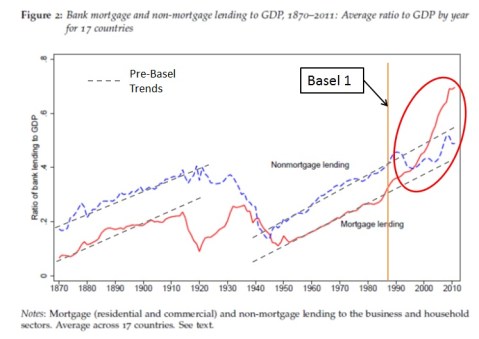

As followers of this blog already know, I view Basel’s RWA concept as one of the most critical factors which triggered the build-up of financial imbalances that led to the financial crisis. In particular Basel 1 – in place until the mid-2000s in the US – only provided fixed risk-weights – and therefore incentives for bankers to optimise their return per unit of equity by investing in asset classes benefiting from low risk-weights (i.e. real estate, securitised products, OECD sovereign exposures…). This in turn distorted the allocation of capital in the economy out of line with the long-term plan of economic actors.

Since the introduction of IRB and internal models by Basel 2, it has been uncertain whether banks using their own models to calculate risk-weights made it more or less likely for misallocations to develop in a systemic manner. There are two opposing views.

On the one hand, more calculations flexibility can give banks the opportunity to reduce the previously artificially-large risk-weight differential between mortgage and business lending for example, thereby reducing the potential for regulatory-induced misallocation and representing a state of affairs closer to what a free market would look like.

On the other hand, there are also instances of banks mostly ‘gaming’ the system with regulators’ support. Those banks usually understand that regulators see real estate/mortgage lending as safer than other types of activities and consequently attempt to push risk-weights on such lending as low as possible. This often succeeds and gains regulatory approval, and it is not a rare sight to see mortgages being risk-weighted around 10% of their balance sheet value (vs. 50% in Basel 1 and 35% in Basel 2’s standardised method). If they do not succeed in lowering risk-weights on business lending by the same margin, this exacerbates the differential between the two types of activities and adds further incentives for banks to grow their real estate lending business at the expense of more productive lending to private corporations.

Now Basel 3 is finally introducing floor to banks’ internal models. The era of the 10% risk-weighted mortgage has come to an end. Once fully applied, asset classes’ risk weights will not be allowed to be lower than 72.5% of the standardised approach value. Unless I am mistaken, this seems to imply a minimum of about 25% for residential mortgages.

Now whether this is good or bad depends on our starting point. If banks, on aggregate, tended to game the system, amplifying the differential vs. the free market, then this floor is likely to reduce the difference between low and high risk-weight asset classes. However, if on aggregate internal models’ flexibility represented an improvement vs. Basel’s rigid calculation methods, then this new approach will tend to deteriorate the capital allocation capabilities of the banking system.

Indeed, the critical concept here is the differential between Basel and the free market. A free market would also take a view as to how much capital a free banking system should maintain against certain types of exposures. While there would be no risk-weight, market actors would have an average view as to the safe level of leverage that free banks should have according to the structure of their balance sheet. In order to simplify this concept of capital requirements in a free market for this post, we can translate this view into a ‘free market risk-weight-equivalent’. Perhaps I’ll write a more elaborate demonstration another time.

So let’s assume a free market in which, on average, mortgages are risk-weighted at 40%, lending to large international firms at 50% and to SMEs at 70%. As this represents a free market ‘equilibrium’, there is no distortion in the allocation of loanable funds. Both corporate and mortgage banks are able to cover their cost of capital at the margin.

Now some newly-designed regulatory framework called, well… Bern (let’s stick to Swiss cities), comes to the conclusion that mortgages should be risk-weighted 50%, and lending to any corporation 100%. While this represents an increase in the case of all types of exposure, the differential between mortgages and corporations is now 50%, whereas it used to be just 10% and 30% under the free market. As a result, bankers whose specialty was corporate lending will have to adjust the structure of their balance sheet if they wish to maintain the same level of profitability. Corporate lending volume is likely to decline as the least profitable lending opportunities at the margin are not renewed as they now do not cover their cost of capital anymore. The outcome of this alteration in risk-weight hierarchy is a reduction in the supply of loanable funds towards the most capital-intensive asset classes. This reduction potentially leads to unused (or ‘excess’) bank reserves released on the interbank market, lowering funding costs and making it possible to profitably extend credit to marginal borrowers within the ‘cheapest’ (from a capital perspective) asset classes.

So this latest Basel reform, good or bad? Existing research is unclear. As I reported in a previous post, researchers found a set of results that seemed to confirm that German banks on aggregate tended to ‘game’ the system using regulatory-validated internal models. However, Germany is a very peculiar and unique banking market and this result may not apply everywhere, and this research doesn’t tell much about the differential described above.

Another research piece published by the BIS showed some confusing results. Among a portfolio of large banks surveyed by the BIS, median risk-weights on mortgages were down to a mere 17%, whereas median SME corporate lending stood at 60% and large corporate lending 47%. Clearly mortgage lending represented the easiest way for banks on aggregate to optimise their RoE, and it does look like the banks surveyed tried to push risk-weights as low as possible in a number of cases.

We could argue that those risk-weights are too low for all those lending categories and therefore endanger the resilience of the banking system. This is indeed possible, but not my point today.

Today, I am not interested in looking at the absolute required amounts of capital that should be held against exposures, but at the relative amounts of capital across types of exposures. I am exclusively focusing on loanable fund allocation within the economic system as a whole. From a systemic point of view, risk-weight differentials matter considerably as explained above.

Basel 1’s risk weight for all corporate exposures stood at 100%, while Basel 2’s were more granular, with 50% for corporations rated between A- and A+, 100% between BBB- and BBB+ and 150% between B- and BB+. This rating spectrum covers the vast majority of small to large companies.

Now look at the differentials. The differentials in risk-weight between the Standardised Method and IRB for an average large industrial company rated in the BBB-range and an average SME rated in the BB-range are respectively 53% and 90%. Between mortgages and the same average corporates under IRB? 30% and 43%, whereas it used to be 65% and 115% under the rigid Basel framework. No wonder business lending growth started slowing down to the benefit of real estate lending since the introduction of Basel.

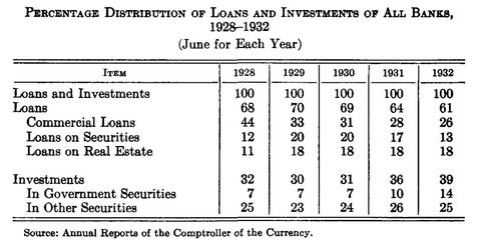

How will Basel’s ‘output floors’ affect those differentials? Here again it is hard to say. If the asset class differentials seen under IRB represented those that would be prevalent in a free market, then Basel’s new output floor is a big step backwards. My intuition indeed tells me that IRB was an improvement: banks’ balance sheet mostly comprised commercial loans in the past (see chart above and the table below on US banks from C.A. Phillips ‘Banking and the Business Cycle), and it looks highly unlikely that bankers would held two, three or four times more capital against those loans as against mortgages or sovereign exposures. Seen this way, this latest Basel twist is bad news.

PS: while most economists and virtually all politicians are unaware of the potentially devastating effects of their bank capital requirements alchemy, they do understand that lowering risk-weights/capital requirements on some types of exposures has the effect of boosting them.

Politicians’ latest brilliant idea? Lower requirements for ‘climate financing’ “in a bid to boost the green economy and counter climate change.” Perhaps time they looked at the overall picture and start wondering how on Earth real estate markets, securitised products and sovereign debt are so attractive to the financial sector?

Back to blogging, and to Basel’s latest twists

After a very long break, I finally decided to start blogging again. This break was due to a very busy lifestyle since last summer: getting back home at 11pm on most week days is not necessarily conducive to quality blogging. As a result of the combination of high workloads and plenty of other activities, and with high level of exhaustion as a result, I realised that blogging was at the bottom end of my list of priorities. On my few free weekends, the few hours of relaxation I could get became a much more appealing option.

Moreover, the post-crisis debate around banking theory and regulation had almost vanished from social and mainstream media amid the benign economic environment. The publication frequency of interesting economic research pieces and other thought-provoking economic commentaries had also declined sharply. There wasn’t much to fight for as there was no one to debate. Not even an endogenous money theorist in sight. Motivation was low.

This state of affairs couldn’t last of course. The accumulation of regulatory news and some (admittedly limited) renewed attacks against free markets and banking on social media were enough to reignite my motivation and finally force me to find enough time to put together a few posts. \My non-blogging activities remain pretty time-consuming; therefore posts are likely to be few and far between.

So where to start? The (apparently) final and long-awaited completion of the new Basel 3 rulebook has been recently published. While I was originally planning to dissect some of its features in this post, it rapidly became clear that a whole separate publication was necessary. So there you go: tomorrow I’ll publish another post on my favourite topic, Basel regulations. And it will be wonkish.

What’s going on?

The post-crisis politico-regulatory consensus is breaking down. There have been tensions over the past couple of years, but overall the illusion of harmony between governments, regulators and central bankers remained. As memories from the crisis fade, politicians facing elections are doing their best to undermine the very system they so vehemently used to support.

We already knew that Germans were complaining about the impact of the post-crisis regulatory framework in the small savings and cooperative banks of the country, and that this was reflected to an extent by the debate in the US over the slow disappearance of their small regional banks (while large banks kept growing). We also already knew that Trump could not be counted among the supporters of Dodd-Frank, the US-flavoured implementation of Basel 3. Elsewhere, dissensions had been relatively muted. Until now.

Italy could be about to undermine the whole European banking union concept by attempting to put in place a large bail out of many of its struggling banks. The whole post-EU regulatory framework was set up in order to prevent such discretionary actions and preserve the single market by forcing losses onto certain types of creditors and coming up with detailed bank resolution frameworks. And of course shield the taxpayer from paying the bill. But it was clearly naïve of EU regulators to underestimate political opportunism.

After years of experiencing growing discretionary powers – encouraged by politicians – the ECB is now complaining that the European Commission might restrict its power. They see ‘considerable problems’ with limitations on ‘supervisory flexibility’, according to Reuters. In other words rules are not acceptable, but discretionary power with limited accountability is. Then one wonders why governments don’t feel bound to rules either.

Meanwhile thirteen smaller EU states are rebelling against the new banking rules in the EU, which give less power and discretion to national regulators under the ‘banking union’ concept. In short, everyone wants a banking union and common rules but no one wants to follow those rules. Politics at its best.

And regulators keep making sense, by fining banks “for being late to explain why an announcement was late”, according to City AM.

It’s very unclear what the outcome of all those political changes will have on the international banking system but banks would probably like to avoid another extra decade of regulatory uncertainty.

PS: Due to a very busy schedule, I haven’t been very active recently, but do have a few posts in the pipeline, some based on recent interesting pieces of research. I’ll do my best to publish them as soon as I can.

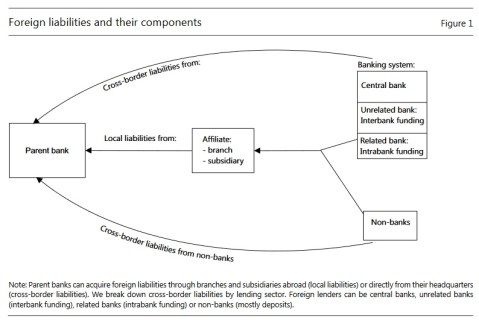

Intragroup funding: don’t build the wall

Three years ago, I wrote about the importance of intragroup funding, liquidity and capital flows within a banking group composed of multiple entities – often cross-border, as it is common nowadays. This series of posts started by outlining recent empirical evidence, which suggested that intragroup funding – or, as academics called it, ‘internal capital markets’ – benefited banking groups by allowing the efficient transfer of liquidity where and when it was needed within the multinational bank’s legal entity structure, thereby averting crises or at least dampening its effects, and solidifying the group as a whole.

Follow-up posts described historical experiences and compared the relative stability of the US and Canadian 19th century branching systems: Canadian banks demonstrated a much higher level of financial resilience thanks to their ability to open branches nationwide, compared to the great instability and recurrent crises experienced by large US state banks – whose ability to open branches in other states or districts was severely constrained by law – and later ‘unit’ banks, which were not allowed to open branches altogether. The series also included the example of a modern banking model that combined characteristics of both the fragmented 19th century US and great resilience, thanks to its peculiar liability-sharing, funds transfer mechanism and cross-control structure: the German Sparkassen Finanzgruppe (saving banks group; see post here).

Of course, throughout this series I kept pointing out that all empirical and historical evidence actually went against the current regulatory mindset of fragmenting and siloing banking. Since the financial crisis, regulators have fallen into a very damaging fallacy of composition: their belief that making each separate entity of larger integrated banking groups stronger and raising barriers between them will strengthen the system as whole is deeply flawed.

Last month, a new paper confirming the critical aspect of intragroup liquidity transfers for financial stability was published (Changing business model in international funding, by Gambacorta, van Rixtel and Schiaffi). This paper investigates whether banks altered their funding profile when the financial crisis struck and money markets froze. More specifically, they looked at changes in the nature (retail, wholesale, intragroup…) and origins (domestic, foreign) of the liabilities at holding and parent company level, as well as at branches and subsidiary levels. And unsurprisingly:

Our main conclusions are as follows. Following the first episodes of turbulence in the interbank market (after 2007:Q2), globally active banks increased their reliance on funding from branches and subsidiaries abroad, and cut back on funding obtained directly by headquarters (cross-border funding). In particular, banks reduced cross-border funding from unrelated banks – eg those that are not part of the same banking group – and from non-bank entities. At the same time, they increased intragroup cross-border liabilities in an attempt to make more efficient use of their internal capital markets.

The authors make a great job at summarising the current literature on the topic: there is overwhelming evidence that banks rely on ‘internal capital markets’ to absorb external liquidity shocks. Yet, the authors also highlight that there have been a few drivers of declining intragroup flows, of which the siloing of liquidity and capital by new regulation has been the main one:

Of these drivers, regulatory reform has been the main catalyst of the profound changes observed in global banking and its funding structures in recent years. This includes most prominently Basel III and structural banking reforms, such as the “ringfencing” of domestic operations and “subsidiarisation”, which requires banks to operate as subsidiaries overseas, with their own capital and liquidity buffers, and funding dedicated to different entities. Moreover, several jurisdictions have implemented enhanced oversight and prudential measures, including local capital, liquidity and funding requirements and restrictions on intragroup financial transfers, promoting “self-sufficiency” and effectively reducing the scope of global banking groups’ internal capital markets (Goldberg and Gupta, 2013). In effect, these regulations restrict the foreign activities of domestic banks and the local activities of foreign banks (“localisation”; Morgan Stanley and Oliver Wyman, 2013).

They point out that

“ring-fencing” and “subsidiarisation” may constrain the efficient allocation of capital and liquidity within a globally active banking group and the functioning of its internal capital markets; in fact, these proposals have led to concerns that structural banking reforms may potentially trap capital and liquidity in local pools.

As I mentioned several years ago in my previous series on the topic, this is a real concern. Driven by their fallacy of composition, and with no empirical evidence to justify their reforms, regulators are weakening the system as a whole, repeating the mistakes of the US of the past. Moreover, disjointed discretionary regulatory actions are likely to make things worse when the next crisis strikes: domestically-focused regulators are likely to attempt to protect their own national banking system, preventing domestic subsidiaries from transferring much-needed liquidity to their parents abroad, resulting in a weakened international financial system.

The long-term consequences of trapping capital and liquidity where they are not of any need is unknown. But, constrained by the new rules, the profit-maximising private enterprises that banks are may well decide that putting those funds to use is better than leaving them idle, even if they would have been even more profitably used elsewhere. In turn, this would distort the allocation of capital in the economy, with potentially dramatic economic outcomes.

Worryingly, it has been recently reported that regulatory agencies had in mind an even more drastic idea: the elimination through subsidiarisation of most, if not all, international branches, trapping further capital and funding within entities that never needed to hold such funds in the past. Whether this measure is implemented in the end remains to be seen but one thing is certain: political agendas lead to the total disregard of empirical and historical evidence. In banking as in politics, the new ideological fracture seems to be ‘open’ vs. ‘closed’.

Thicker capital buffers do not prevent banking crises

I know I complained about the sorry state of academic research on banking in my previous post, but not all research makes me despair. In fact, I have long admired a number of ‘mainstream’ academic researchers, such as Borio, as well as Jordà, Schularick and Taylor. The latter’s research is top-notch and what they built what is surely one the best available historical databases of banking. Thanks to their data collection, they provide academics with resources that go beyond the narrow scope of US banking. Their dataset is available online.

Last September, they published a paper titled Macrofinancial History and the New Business Cycle Facts, which is quite interesting, although not as much as their ground-breaking previous papers. Nevertheless, it is based on excellent datamining and I strongly encourage you to take a look. One of the interesting charts they come up with is the following real house price index aggregated from data in 14 different countries. As we can see, real house prices have remained relatively stable (at least within a range highlighted the black lines I added below) until the 1970s. However they started booming from the 1980s, when Basel artificially lowered real estate lending capital requirements relative to that of other lending types.

But it is their most recent paper that particularly drew my attention. Published just a couple of weeks ago and highlighting Bagehot’s quote at the top of this post, Bank Capital Redux: Solvency, Liquidity, and Crisis argues that, contra the current regulatory logic, higher capital ratios do not prevent financial crises. In their words (my emphasis):

A high capital ratio is a direct measure of a well-funded loss-absorbing buffer. However, more bank capital could reflect more risk-taking on the asset side of the balance sheet. Indeed, we find in fact that there is no statistical evidence of a relationship between higher capital ratios and lower risk of systemic financial crisis. If anything, higher capital is associated with higher risk of financial crisis. Such a finding is consistent with a reverse causality mechanism: the more risks the banking sector takes, the more markets and regulators are going to demand banks to hold higher buffers.

As usual, their data collection is remarkable. This time, they collected Tier 1 capital-equivalent* numbers, as well as other balance sheet items, across 17 countries since the 19th century. Here is the aggregate capital ratio over the period:

Unlike what most people – and economists – believe, they also demonstrate that capital ratios were on the rise in a number of countries in the years preceding the financial crisis:

Their finding is a blow to mainstream regulatory logic: capital ratios are useless at preventing crises and may well be a sign of higher risk-taking.

However, some of their findings do provide some justification for capital regulations. They find that

a more highly levered financial sector at the start of a financial-crisis recession is associated with slower subsequent output growth and a significantly weaker cyclical recovery. Depending on whether bank capital is above or below its historical average, the difference in social output costs are economically sizable.

While the fact that better capitalised banks are more able to lend during the recovery phase of a crisis sounds logical to me, I believe this result requires more in-depth analysis: it is likely that regulators in many countries forced banks to recapitalise after past crises or, as it was the case in the US in the post-WW2 era, that banks were also required to comply with a certain type of leverage ratio. This would have slowed their lending growth and impacted the recovery as they rebuilt their capital base to remain in compliance.

It may also be that, as they highlight in some of their previous research, banks suffered more from real estate lending, which was initially seen as safer and requiring thinner capital buffers, but which ended up damaging their capital position further and for longer periods of time once prices collapsed (relative to financial crises triggered by stock market crashes for instance). Whatever the underlying reason, this finding requires more scrutiny and granular analysis.

They also find

some evidence that higher levels and faster growth of the loan-to-deposit ratio are associated with a higher probability of crisis. The same applies to non-core liabilities: a greater reliance on wholesale funding is also a significant predictor of financial distress. That said, the predictive power of these two alternative funding measures relative to that of credit growth is relatively small.

See below the 17 countries aggregate loans/deposit ratio:

This is interesting, as we see that, unlike capital ratios, loans/deposit ratios were quite stable in recent decades relative to long-run average (in particular if we exclude the Great Depression period and its long recovery), around the 100% mark.

However, I will have to disagree with their finding that more ‘wholesale funding’ is a driver behind financial crises, even if there is some truth to it; although I happen to disagree strictly based on the evidence they provide. They base their reasoning on the wrong assumption that all non-deposit liabilities are necessarily other funding sources (see below the breakdown of liability types). This is incorrect: modern large universal banks have very large trading and derivative portfolios, which often account for 20% to 40% of the liability side of their balance sheet (although US banks under US GAAP accounting standards are allowed to net derivatives and therefore report much smaller amounts).

The key to figure out whether a bank is wholesale-funded is simply its loans/deposits ratio. A ratio above 100% indicates that a portion of loans has been funded using non-deposit liabilities. But as we’ve seen above, this ratio has never risen very high in the years preceding the financial crisis and used to be even higher in the 1870s.

Despite those minor disagreements and caveats, their research is of great quality and their dataset an invaluable tool for future analysis.

*Tier 1 capital is a regulatory capital measure introduced by the Basel rulebook

Recent Comments