AI: regulatory arbitrage on steroids?

Pretty much everyone has heard of Fintech by now, but a more focused approach to applying new IT technologies to banking is now the nerdier Regtech. Regtech aims at applying Fintech for regulatory and compliance purposes, simplifying a process that has caused headaches to bankers due to the exponential growth of the rulebook they had to follow, and which has also been a pain on the cost side given the number of extra compliance officers they had to hire in an era of lower revenues.

Indeed, the FT reports that:

Citigroup estimates that the biggest banks, including JPMorgan and HSBC, have doubled the number of people they employ to handle compliance and regulation. This now costs the banking industry $270bn a year and accounts for 10 per cent of operating costs. […]

Spanish bank BBVA recently estimated that, on average, financial institutions have 10 to 15 per cent of their staff dedicated to this area. This heavy investment has been necessary in response to the crackdown by regulators that followed the financial crisis. European and US banks have paid more than $150bn in litigation and conduct charges since 2011, Citi estimated.

What’s the solution? ‘Regulatory technology’:

New technologies mean that banks could make vast savings in compliance, according to Richard Lumb, head of financial services at Accenture, who estimated that “thousands of roles” in the banks’ internal policing could be replaced by automated systems.

Many of recent Regtech developments involve the use of artificial intelligence to simplify compliance issues that are very burdensome from a staff (and cost) perspective. As Deloitte outlines here (and see an interview on the Financial Revolutionist about applying machine and deep learning to investment strategies here):

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) highlights AI, among others, as it has a range of applications in regulatory compliance and reporting. It can be used in analysing complex trading relationships, trading schemes, patterns and communications between banks, exchanges and other market participants. AI can also be employed to monitor internal conduct and communication to clients, comparing it to quantitative metrics such as supervisory input. As AI relies on computer-based modelling, scenario analysis and forecasting, it can also help banks in stress testing and risk management.

But what I find particularly interesting is this bit:

Another field for AI in financial regulations is to simplify the regulations themselves: there are a multitude of different jurisdictions, products, institutional differences and enforcement mechanisms and it is hoped that AI systems are better in collecting and categorizing them according to rules.

Similar points in an Economist article published a few months ago about Watson, IBM’s AI product:

The next area is to provide clarity about rules. They are sorted by jurisdictions, institutional divisions, products and so forth, and then further broken down between rules and guidance. Watson is getting better at categorising the various regulations and matching them with the appropriate enforcement mechanisms. Its conclusions are vetted, giving it an education that should improve its effectiveness in the future. Promontory’s experts are expected to help Watson learn. A dozen rules are now being assimilated weekly. Thousands are still to go but it is hoped the process will speed up as the system evolves. Ultimately, IBM hopes speeches by influential figures, court verdicts and other such sources will be automatically uploaded into Watson’s cloud-based brain. They can play a role in determining what regulations matter, and how they will be enforced.

Below is a useful chart showing all current Regtech areas and start-ups (you can also find it here):

While the industry has not explicitly said it this way (and probably never will), it seems to me that we’re on our way to AI-driven regulatory arbitrage. Once those systems are ready, AI will be able to navigate through the thousands of regulatory pages and extract the most effective ‘regulatory optimisation strategy’ within and across borders.

If all AI systems used by financial institutions reach the same conclusion, this could lead to a build-up of imbalances and systemic risks that could eventually trigger a crisis, following a process similar to that which contributed to the latest financial crisis: Basel rules facilitated the accumulation of imbalances in the credit market towards real estate lending.

It of course remains to be determined whether AI systems reach the same conclusions in the end. But this is likely to happen, for the following reasons: 1. banks whose systems are less effective will progressively attempt to catch up with the competition, leading to harmonisation in the design of those systems and 2. if AI solutions are provided by third-party firms, harmonisation will occur from the start.

A glimpse of hope remains in that the optimal regulatory arbitrage strategy may be different for financial institutions with different business models (mortgage banks vs. universal banks for instance). But let’s not hold our breath: even in this case, imbalances would still occur and universal banks still account for most of the world’s banking assets by far.

For now, explicit regulatory ‘optimisation’ does not seem to be included in the chart above (although the ‘Government/Legislation’ category could well evolve into a more arbitrage-oriented segment). But how long before it does?

Clarifying confusions on capital requirements

As the Trump administration is considering scrapping parts of the enormous Dodd-Frank act, a number of media and economists look alarmed: Dodd-Frank made the American banking system safer, the argument goes, and getting rid of it would lead to another financial crisis.

While long-time readers of this blog know that Dodd-Frank, and the Basel 3 international accords it is based on, merely continue the mistakes of three decades of regulatory overreach that have brought about the largest financial crisis in decades, I thought it was necessary to clarify a couple of points regarding capital requirements.

In this week’s Economist, two articles seem to admit that, while the act indeed represented an unclear regulatory monster of thousands of pages that mostly penalised smaller financial institutions, it also made the system safer by reinforcing banks’ capitalisation.

In an editorial, the newspaper asserts that:

Onerous though it is, however, the act also achieved a lot. Measures to beef up banks’ equity funding have made America’s financial system more secure. The six largest bank-holding companies in America had equity funding of less than 8% in 2007; since 2010 that figure has stood at 12-14%.

In another article, it adds:

Thanks in part to Dodd-Frank, America’s banks are far safer than they were: the ratio of the six largest banks’ tier-1 capital (chiefly equity) to risk-weighted assets, the main gauge of their strength, was a threadbare 8-9% before the crisis; since 2010 it has been 12-14%.

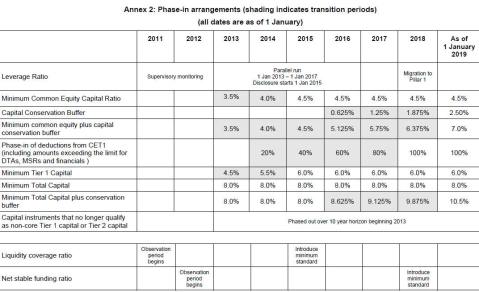

But it is far from clear that Basel requirements are behind banks’ post-crisis thicker capital buffers. See Basel 3 minimum capital requirements below:

Minimum Tier-1 capital requirements are 7.875% (Tier 1 + capital conservation buffer). This is around 2008 level for large US banks. Hardly an improvement at first glance then.

However, let’s also add the recent SIFI capital surcharge, published by the FSB last November: only two institutions qualified for a 2.5% surcharge (only one of them US-based), but let’s add it this figure to our minimum above. We get to a SIFI minimum Tier 1 requirement of 10.375%. This is still an almost 2 to 4% gap with the 12% to 14% average referred to by The Economist above.

Therefore the only conclusion is that there are other parameters and considerations influencing the level of capital ratios upward. One of those parameters is indeed regulatory-related, but is discretionary at bank-level: it is bankers’ own view about the capital buffer they believe they need above the regulatory minimum in order to avoid breaching it in case of sudden large losses. This shows some of the perverse side-effects of strict minima, and I described some time ago that the ‘effective’ capital ratio was actually the differential between the level maintained by the bank and the regulatory minimum. And this ‘effective’ buffer tends to narrow rather than thicken as minima are raised.

The second is exogenous to bank’s decision making-process: the financial crisis has taught a number of investors not to get fooled by headline regulatory capital ratios. Consequently, investors now ask for higher levels of capital in order to compensate for the lack of clarity regarding the quality of capital*. Given that risk-weights (another regulatory construct) have a considerable influence on the level of capital ratios, investors also ask for extra capital buffers to compensate for the distortions they inevitably introduce in the headline figures.

Consequently, had minimal requirements stayed the same, investors would have been highly likely to demand extra protection against the uncertainty introduced by…..those same regulatory requirements.

In the end, the assumption that banks are much better capitalised and that regulation/Dodd-Frank is responsible for this is questionable.

*While Basel 3 and Dodd-Frank have indeed also touched upon the issue of capital quality, it remains unclear how a number of so-called hybrid, or ‘complementary Tier 1’, instruments will perform under stress and legal challenges.

PS: this blog post could have entered into a lot more details about the parameters driving the thickness of capital buffers, but it would then have to be split into 3 or 4 different posts. At least. So please read some of my other posts on the topic to get the bigger picture as this is a complex issue.

Back again

For real. After almost six months without writing anything, I finally got all the green lights I needed to resume both blogging and external contributions. I still won’t have the time for more than a single blog post per week or so, but my pipeline of potential posts has grown over the past few months and should keep me busy for the foreseeable future.

To be fully honest, I really hesitated to write this post. I simply didn’t know what to say. Times are now different from when I started writing back in 2013. There is less media focus on banking crises and unconventional monetary policies. Media’s attention has shifted towards topics such as Trump, Brexit and political correctness and, following years of never ending banking reforms, booming financial markets and declining unemployment, there now seems to be less urgency to understand what went wrong with our global financial system.

Yet there is still plenty of work to do: most people, journalists and academics still believe that a deregulated financial system is inherently unstable and caused the global financial crisis that started almost a decade ago. Much like economic myths such as ‘FDR’s New Deal and WW2 saved the economy from the Great Depression’ have been blindly followed by generations of academics, allowing the ‘banking is inherently unstable’ story to settle into mainstream econ textbooks would build the foundations of the next major financial crisis.

Nevertheless, it does look like the new Trump administration will bring banking and financial regulation back in the spotlight as there is talk of repealing some of the Dodd-Frank act measures. It will be interesting to follow the evolution of this idea, for the following reasons: 1. there has never been any real deregulation of the banking system on aggregate, 2. it will trigger some international regulatory competition as other jurisdictions, such as the EU, seem unlikely to leave their own banks at a competitive disadvantage, 3. we could find out how flexible the regulatory framework of a single country is within an internationally agreed agreement such as Basel 3 (which is the basis of the Dodd-Frank act), and 4. we’ll also potentially find out the extent of regulatory capture in the American economy: let’s see how eager large banks are to evolve in a less regulated environment.

It is possible that the Trump administration will only repeal the least damaging and distortive measures of Dodd-Frank. However, if they do surprisingly succeed in repealing major reforms such as Basel 3 capital and liquidity requirements, the implications for international agreements could be huge: Basel could effectively be dead in the water.

How likely is this scenario to happen? Hard to say. My fear remains that repealing parts of the Basel 3 agreements on a unilateral basis would further complexify and opacify the current financial system and bring about massive distortions through international regulatory arbitrage.

Anyway, it’s too early to speculate so I’ll keep monitoring.

Recent Comments