Blockchain vs. regulators and Pareto optimality

As the blockchain technology keeps getting more and more mainstream, SNL reports (gated link) that a top regulator, David Wright, the head of IOSCO (International Organization of Securities Commissions), believed that the blockchain could facilitate regulators’ role by giving them instantaneous access to a total market overview as well as to particular trades and their respective counterparties. He added that, as a result, collateral requirements could be slashed.

As SNL sums up:

Regulators hope that it could revolutionize financial infrastructure, potentially providing them with an omniscient and instant picture of every trade in a market, complete with information about price and the identity of all parties involved.

Wright put a particular emphasis on market abuse:

You know who’s bought the particular product, so that’s good from a market abuse perspective, of controlling market abuse.

He is right; at least partly. Blockchain could indeed seriously simplify and streamlin the infrastructure of financial markets. We have talked about this on this page a number of times, but it isn’t the topic of this post.

Where Wright gets it partly wrong, is when he believes regulators will still be needed to regulate financial institutions. Well, the thing with blockchain technology is that the system doesn’t even need many regulators anyway, because all trades are transparent and accessible by anyone. Intra-firm trade controls are outsourced to an informal and virtual third-party: the blockchain.

Consequently, the number of regulators could be drastically cut. And this is where regulators may end up not loving the blockchain so much.

Regulatory bodies have grown significantly since the crisis, have developed strong political links and influence and have become a bigger source of public sector employment. They have therefore become interest groups. Let’s look at some numbers.

In the UK, the FSA, previously the sole financial regulator in the country, used to employ a total of 1,796 staff as of early-2008. Within a year, it added 537 staff (+30% yoy). It was then split into two different entities, the FCA and the PRA, which as of March 2015 employed 4,034 staff. FCA staff number increased by 17% just in 2014. But the BoE is also now in charge of regulating banks, and its staff (which I believe include PRA staff) totalled 3,868. Meaning there are now 6,887 people who work in official regulatory bodies in the UK (the BoE wasn’t a regulator before the crisis). This is a 283% increase over the past seven years.

Now, I’d like to provide readers with similar numbers for the US and the EU, but given the complexity of the new regulatory frameworks in each of those jurisdictions, it’s a task that requires a little more than a short blog post. In the EU, the ECB and other EU regulators have taken over national regulators, although some implementation and monitoring remains in the hand of domestic authorities. In the US, well, the chart below (from The Economist) speaks for itself. So it’s hard to come up with a pre/post crisis comparison. But there is no reason to believe that the situation differs from that in the UK.

Note that the growth of state-related agencies with expanding powers creates particular Public Choice issues. I see a number of problems here:

- Regulatory bodies are unlikely to prove an exception to the rule and not transform into interest groups (i.e. the usual ‘we need more budget, more staff, more power’).

- Regulatory bodies could become victim of regulatory capture, in the pure crony capitalist tradition.

- The consequence of any of the two points above is that anything that is likely to disrupt this cosy business/regulatory model faces high hurdles, even if beneficial for society as a whole.

Let’s now factor in the blockchain. Despite the fact that a number of regulators clearly see the positive effects that this technology could have on financial markets stability and transparency, adopting it would lead to 1. a loss of discretionary power/influence, and 2. large job losses at regulatory bodies.

Consequently, regulators are strongly incentivised to slow down the adoption of blockchain-like techs. See this recent speech of SEC’s Kara Stein at Harvard Law School, which clearly illustrates the ambivalent stance regulators are in at the moment. Whether or not they eventually succeed as the whole industry moves towards its implementation is another question. Do expect some resistance nonetheless.

Finally, I’d like to point out the irony of this situation. Regulators are often appointed to correct what a number of (often Keynesian) economists view as ‘market failures’ (hint: they are wrong). Their idea is that, through appropriate regulation, a so-called Pareto optimal situation can be achieved: as a result of more stable markets, nobody ends up worse off, and at least a few people end up better off. Hence the irony of witnessing the same regulators effectively preventing us from reaching Pareto optimality through financial innovation. Public Choice theory is as valid as ever.

PS: Don’t get me wrong though. I am not saying that blockchain is the Holy Grail. But regulators are highly unlikely to be better placed than markets to understand the potential implications of widespread blockchain adoption.

Further evidence of macro-pru illusion

Back to blogging after two weeks travelling (though still busy until Christmas!).

Over the past few weeks I read a number of articles suggesting that the outcomes of real-life macro-prudential experiments were rather poor, to say the least. Those complement the various academic studies I had already commented on since the start of this year (see here and here).

The Economist reported that the Hong Kong housing market jumped by 21% over just…a single year, and has doubled over the past five years. And this happened despite the fact that local regulators have progressively introduced harsher and harsher macro-prudential measures: it raised the LTV constraints on new mortgages exactly seven times over the period. Any effect? None.

The Economist again reported that another sort of macro-prudential measure was being used in Sweden, with little effect. Swedish regulators required at least a 15% down payment for mortgages (i.e. max 85% LTV) in 2010, then raised the capital requirements that banks need to hold against mortgages in 2013, and then again raised an aggregate capital requirement earlier this year. But the property market has still boomed. Moreover, the newspaper says that even when tools targeting specific types of credit are put in place, the financial sector (and demand) responds by extending other types of credit:

the allure of cheap loans is so great that households in Sweden and beyond will find ways around the restrictions that remain in place. When the Slovakian government put limits on housing loans, banks boosted other forms of lending to bridge the gap. In Sweden, so-called “blanco-loans”, more expensive unsecured loans, can be used for that purpose. All told, credit is still growing and asset prices climbing, despite regulators’ efforts.

Earlier this summer, two IMF researchers published a paper listing and analysing the macro-pru policies and their effects in five different countries over the past decade or so, including Sweden and HK (the other ones being the Netherlands, New Zealand and Singapore). While in a few instances it might be a little early to judge the results of those implementations, it is clear that macro-pru has had only very minor impacts on only one of the markets they looked at. The only (small) positive impacts they found involved potentially enhanced resilience of the banking sector in some countries; which is even arguable as a percentage point more capital is unlikely to represent enough of a buffer to significantly absorb losses emanating from a collapsing NGDP driven by a housing market free-fall.

Let’s see what this paper has to say (I modified some of their charts below on purpose).

Hong Kong:

The impact of tightening macroprudential policy on property prices is less clear; property prices leveled off briefly following the measures but resumed their upward trend in mid-2014.

Also, remember this chart from a previous post (original paper here). Red dots represent tightening, and blue dots loosening, over a longer time frame. Effectiveness? Close to zero.

The Netherlands: No impact so far and no conclusion, but the housing market was already falling following the financial crisis anyway.

New Zealand:

Following the imposition of the caps there was a sharp fall in loans with high LTVs. Housing loans with high LTVs made up 5.2 percent of total new commitments in February 2014 compared with 25.1 percent in September 2013. In addition, the slowdown was accompanied by lower house sales and a lower growth in house prices.

Here, macro-pru had some minor effects (of course that LTV fell as they were capped), but what the paper doesn’t mention is that total lending growth has resumed and is concentrated in the lower than 80% LTV bracket. Moreover, house prices growth has also resumed. So, some positive effects but temporary and minor.

Singapore:

The combination of macroprudential and fiscal measures was effective in building buffers and moderating price appreciation in Singapore. The recent macroprudential measures lowered the average LTV ratio on new housing loans, and increased the share of borrowers with single mortgages. […] The rise in housing prices has abated. The HDB Resale Price Index declined eight percent from its peak in mid-2013 to the end of 2014 following a rise of almost 50 percent since end-2008. Similarly, the Private Residential Property Price Index declined by five percent from its peak in the third quarter of 2013 to the end of 2014. The decline in housing prices was accompanied by a sharp drop in transaction volumes. Annual new home sales in the private residential market declined by ⅓ in 2013 and by 50 percent in 2014

Singapore is probably one of the rare successes of macro-pru. But even there, disentangling the effects of macro-pru from those of Singapore economic difficulties and housing oversupply (leading to a natural correction) is not as straightforward as the IMF paper seems to believe. In particular as most of the fall in house prices occurred before the harshest constraints were put in place.

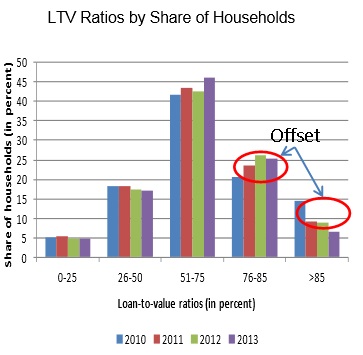

Sweden: Some shifts from the 85%+ LTV bracket to the 75-85%, but overall no effect on the housing market.

Overall, the paper concludes that

While there is some early evidence that the measures taken have enhanced banking system resilience, it is still early to determine their full impact.

Translation: macro-prudential measures’ effectiveness is very limited.

Of course domestic restrictions on housing supply still weigh on those countries’ property prices. But that’s not the whole story. As I have repeatedly said on this blog, housing booms have become a common occurrence throughout the world since the introduction of the Basel framework at the end of the 1980s (the parallel introduction of inflation targeting by central banks may well have amplified the trend). All countries with and without building restrictions have been affected, albeit at varying degrees.

What about the counterfactual? Some could argue that without the implementation of those measures, the situation if all those countries would have got even worse. But merely limiting a crisis or a the inflation of a bubble is not the goal, is it? Macro-pru is being sold to the public as an effective anti-crisis micro-management tool.

But what’s really scary is the absolute faith that most central bankers and regulators have in macro-prudential tools. Virtually all their speeches (see this search on the BIS website), presentations and publications praise macro-pru effects in taming the financial sector, while rejecting the idea that monetary policy is the right tool to do so (unsurprising as they keep trying to justify maintaining interest rates at their lowest levels in history).

As The Economist (itself a fan of macro-prudential policies 50% of the time, go figure) rightly sums up:

Ask a central banker what regulators should do when rock-bottom rates cause house prices to soar, and the reply will almost always be “macropru”. Raising rates to burst house-price bubbles is a bad idea, the logic runs, since the needs of the broader economy may not square with those of the property market. Instead, “macroprudential” measures, meaning restrictions on mortgage lending and borrowing, are seen as the answer. But this medicine is hard to administer, as Sweden’s housing market vividly illustrates.

In fact, it is very misleading to think of the needs of the broader economy that would in some ways be disconnected from those of the property market. The economy is organic and resources move from one area to another, where they are needed, or where incentives make them more profitable. As resources are scarce, there simply can’t be a disconnect between the various sectors of the economy. If an ‘imbalance’ appears somewhere, it must mean that there is an equal imbalance of the opposite sign somewhere else. As a result, trying to boost or tame particular sectors is counterproductive. Resources will still mostly flow towards the areas of least resistance.

The Basel banking framework introduced less resistance in the property sector (as well as in the sovereign and structured financial product spaces), and higher resistance in most of the rest of the economy. The ‘imbalances’ that lead to the apparently differing ‘needs’ of the property sector and of the broader economy are mere reflections of a more fundamental and deeper and bigger imbalance.

Macro-prudential policies merely represent an illusion of effective central planning. Not only its effectiveness is close to zero but it can only become effective when its effects are so harsh that they risk paralysing economic activity without fixing the underlying distortions in the economy.

Recent Comments