Negative interest rates and banking instability

Negative interest rates are back in the news as they seem to be generalising. This is a topic I have covered several times over the past couple of years.

Back in June 2014 in particular, I wrote two posts about negative interest rates on ECB deposits. Here, I explained the negative impacts of this policy on banks, from an accounting and profitability perspective. I concluded:

Many European banks aren’t currently lending because they are trying to implement new regulatory requirements (which makes them less profitable) in the middle of an economic crisis (which… also makes them less profitable). As a result, the ECB measures seem counterproductive: in order to lend more, banks need to be economically profitable. Healthy banks lend, dying ones don’t.

The ECB is effectively increasing the pressure on banks’ bottom line, hardly a move that will provide a boost to lending. The only option for banks will be to cut costs even further. And when a bank cut costs, it effectively reduces its ability to expand as it has less staff to monitor lending opportunities, and consequently needs to deleverage. Once profitability is re-established, hiring and lending could start growing again.

Subsequently, I wrote about the fact that some German banks had started charging their non-retail customers for holding deposits with them. I started with the following bank’s (basic) economic profit equation introduced in the post mentioned above:

Economic Profit = II – IE – OC – Q

where II represents interest expense, IE interest income, OC operating costs (which include impairment charges on bad debt), and Q liquidity cost.

From this equation, I showed how banks attempted to pass negative deposit interest expenses onto some customers, thereby neutralising the effect the ECB was expecting, that is: lending growth.

But of course, ECB economists aren’t that clueless, and knew that this could happen. So they hoped that a second effect could ‘stimulate’ aggregate demand: that customers believe themselves to be better off spending their money (pushing inflation up) rather than getting effectively taxed.

Unfortunately, this relies on

- a simplistic and very mechanical view of human beings, and

- a flawed understanding of banking mechanics.

I addressed point 2 in several posts. In a banking system relatively free of regulatory constraints, as banks’ customers attempt to spend as quickly as possible after getting their salary paid in, the velocity of the money supply increases, but so does banks’ liquidity cost (Q in the equation above). Why? Because banks’ funding structure becomes more unstable, leading them to accumulate more low-risk, liquid assets as a share of total assets in order to face possible adverse clearing and in order to reduce the liquidity mismatch between the growing turnover of their deposit base and their longer-term investments.

Worse, if customers do not spend but instead merely decide to withdraw their deposits and keep their cash under their mattress, not only is bank’s funding structure more unstable, but it also shrinks, leaving banks with fewer funds to ‘lend out’.

In both case, credit supply (particularly long-term) is likely to get affected and bank shareholders/bondholders are likely to require higher returns to offset what they perceive as higher liquidity risk. Given that returns are already pretty depressed, no wonder I recently said that banks were bleeding shareholders.

Moreover, recent banking regulation amplifies this phenomenon. Basel 3 introduced the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), which require banks to hold a certain type and amount of liquid assets and ‘stable’ funding on their balance sheet to face short-term withdrawals. From the instability and increased deposit turnover I described above, it seems obvious that those rules would further constraint banks’ ability to freely decide how to allocate credit (and how much).

Those are conclusions I reached already two years ago. Am I the only one to hold such view? Apparently not, given what a number of analysts have recently said. According to The Telegraph:

Sub-zero rates would discourage banks from expanding their operations, crimp cross-border lending in the eurozone and result in higher credit costs in the beleaguered currency bloc, according to Morgan Stanley.

“This is all contrary to the ECB’s desire to ease credit conditions and support financial stability,” said Mr van Steenis.

“It is an unnecessary and dangerous experiment to take in case there are non-linear impacts on deposit stability and financials stability writ large.

“The ECB’s action is flipping from a positive to a negative for European banks,” he added.

What about point 1 above? Well, a recent survey by ING provides some colour as to how people would react if nominal rates on their saving accounts turned negative (real rates have often been negative but, you know, money illusion).

Those are some of the results:

The chart doesn’t show the percentage who responded ‘spending more’. So here is the answer (my emphasis):

No less than 77% said that they would take their money out of their savings accounts if rates went negative. But only 12% would spend more, with most suggesting that they would either switch into riskier investments or hoard cash ‘in a safe place’.

So much for raising inflation…

Of course, once effectively facing negative rates, those respondents might behave differently, but the survey highlights that the effects of the policy on aggregate demand may not end up as positive as central banks expect, while harming the banking system and hence making it less able to lend for productive purposes.

PS: However, and as usual, I strongly disagree with Frances Coppola’s assertion (about excess reserves) that:

But of course the reserves do not disappear from the system. They simply move to another bank, which then incurs the tax. The banking system AS A WHOLE cannot avoid negative rates on reserves.

No, as I and George Selgin recently described, if the whole system extends credit, excess reserves gets converted into required ones. Hence the tax disappears. Nevertheless, this is a lengthy process, as operationally, it is almost impossible for banks to increase their loan book/buy assets quickly enough to offset the recent extremely rapid growth in the monetary base, in particular at a time of new regulatory implementation. (please note that this reasoning only applies to policies that only charge negative rates on excess reserves)

PPS: I also wrote about whether or not a free banking system would ever apply negative rates here.

Banking and social justice don’t mix very well

I recently came across the following piece from Tony Greenham on the RSA website: “Banks should serve the real economy – How?”

It’s something I have often read in the media, most of the time written by people who don’t really understand the purpose of banking in the economy. It often comes from a certain part of the political spectrum, and seems to be a cover for ‘social justice’ applied to banking. And it’s a recipe for disaster.

The argument is typical: banking should be ‘fair’ and ‘serve the real economy’. Yet, as with social justice in general, no definition is ever provided of what ‘fair’ banking is and how it can more adequately help the real economy. As with ‘social justice’, all criteria of fairness inevitably remain very subjective and variable in time, place and individual mood. Moreover, what a number of people view as ‘fair’ is often in direct contradiction with the rule of law.

All this logic comes down to the view that banking is another type of ‘utility’. That it should provide services for all that need them. No, it isn’t. Banks do not have a duty to provide credit on demand. Forcing them to do so would inevitably lead to bad lending decisions and hence large losses, and politicians and the public would once again blame those ‘greedy’ bankers who took senseless risks (despite encouraging them in the first place). This is what happened in the US with subprime mortgages (and the Community Reinvestment Act Greenham seems to find useful). See Calomiris and Haber’s Fragile by Design to understand the serious implications that ‘fairness’ had on the US banking system before the crisis.

Greenham’s post falls into the same trap. Let’s leave aside the fact that his post is technologically quite backward-looking (branches and transactions are now increasingly replaced by mobile phones and technologies like blockchain, and the shrinking number of customers using branches can continue to do so) and also avoid any discussion of modern constraints on banking; that is: regulation (branches are great if you can cover the cost of operating them).

He blames banks, free markets and ‘co-ordination failure’ for the disappearance of branches whereas he should have focused on ballooning regulatory and compliance bills that accelerate that change beyond the pace justified by technological transformation.

But where I am really worried is when I read this:

But bank deposits are underwritten by the state. Their acceptability depends on the state. They are arguably therefore a public good. Certainly, how much money is created in total, and to which economic sectors it is lent, are matters of the highest public interest. So here is the problem – there is no guarantee that if you add up all the individual lending decisions of banks that you will arrive at the optimal level of credit growth and allocation for the economy.

In fact, theoretical and empirical evidence suggests the opposite. We see too much credit creation during booms, and too little during recessions. Too much credit flowing to real estate and financial asset speculation, and too little to SMEs and infrastructure investment.

Individual banks cannot solve this problem. More competition cannot solve this problem. Rigid free-market ideology cannot solve this problem.

This is the sort of superficial thinking that I have tried to fight since I started writing on this blog. Typically, this sort of ‘social justice’ reasoning never tries to dig a little deeper below the surface. This would lead to dreadful conclusions: that the proposed solution (i.e. often government intervention) would actually target outcomes of previous government intervention. So better avoid digging altogether and coming to terms with unpleasant findings, and continue to believe that banking is ‘inherently unstable’ and doesn’t know how to efficiently allocate capital in the economy without the guiding hand of government officials.

The usual Public Choice and Hayekian critiques also apply. The information fragmentation and political incentives prevent policymakers from taking the right decisions in a timely fashion. Moreover, the highly subjective and fluctuating ‘social justice’ criteria lead to discretionary decision-making and regulatory uncertainty. This does not represent a recipe for economic success.

So what to do? Set banking free. The ‘invisible hand’ behind bankers’ lending decision will, on aggregate, allocate credit in more effective manner than any central authority and its distorted and ever changing incentives ever can. There is a reason behind the financial and real estate booms of the last few decades. And it lies in artificial rules designed by a number of ‘great minds’. Not in a ‘rigid free-market ideology’ that never was.

PS: we could say a lot about his assertion that deposits are a public good, but it isn’t the topic of this post.

Banks are bleeding shareholders

There has been a lot of discussion about the bank stock sell-off in the media. A lot of analysts and journalists have been wondering what’s going on in face of what looks like an overreaction. I don’t have an answer to that question, as I’m not sure that fundamentals justify that sell-off. Perhaps some hedge funds and speculators have been temporarily amplifying the fluctuations. But I’m not omniscient and it is possible markets have noticed something that I missed.

What I believe though, is that this sell-off has been artificially exacerbated by traditional bank shareholders, who can’t stand that situation anymore, in particular in Europe. What I mean by ‘that situation’ is everything that’s been happening to the banking sector since the crisis.

Imagine that you’re a bank shareholder. The bank you invested in survived the crisis but stopped paying dividends to you and left you with a deep negative return on your portfolio of shares. In order to start growing again and comply with new regulatory requirements, the bank asks you to invest more capital, promising a return to profitability soon. You are glad the institution survived the crisis, which may signal its superior risk management relative to competitors, so you provide that extra capital.

Unfortunately, regulation tightens further and central banks push interest rates down, sometimes into negative territory, compressing the bank’s net interest margin and depressing its profitability. To cope with this temporary pressure, the bank asks you to invest a little bit more capital, possibly in one of those new fancy hybrid capital instruments that pay high coupons without diluting the equity holder base. Fine you think, it’s for a good reason: this will be a temporary pain to bear in order to stimulate the economy and make the financial system safer, which should soon lead to prospects of higher and more stable return.

Unfortunately, authorities and regulators in a multitude of countries believe this time to be appropriate to fine banks, including yours, for past and current misbehaviour, leading to your bank’s capitalisation weakening again. A little bit annoyed, you tell yourself that it is the last time you inject extra capital into that bank. And anyway, what else could happen? You’ve pretty much lived through everything now.

Unfortunately, far from improving under all the central bank stimulus, the economy of a number of countries start declining, leading to fears for the world economy. In case of a global, or multi-country, recession, the banking sector is likely to make some losses, prompting some investors to sell their shares. As a result, the bank you invested in is likely to ask you for some extra capital sooner or later. No gain on your portfolio is in sight. “I’m out” you say, fed up.

The past eight years have been so badly managed by policymakers, central bankers and regulators, that I hope it’s going to enter history books as a good example of what not to do following a large systemic financial crisis.

Whether or not one wishes to increase the regulatory oversight of the financial sector, the worst possible time to do it is while surviving banks’ health remains extremely weak. Bankers, not only have to deal with legacy issues on their own balance sheet, but also have to implement fundamental and very disruptive changes to the same balance sheet.

Add in very low internal capital generation due to depressed profitability in a low interest rate environment (and amid the exit of a number of now unprofitable businesses), as well as huge fines that literally disintegrate capital*, and you end up with a banking sector that cannot comply with regulators’ constant demands without continuously raising capital from their existing (or new) shareholders without ever rewarding them.

Policymakers seem not to have understood one of the main tenets of capitalism: opportunity cost. There is no point, as an investor, to become a shareholder in an institution that cannot generate even close to its cost of capital in the long run. And, relative to 2008, the long run is now.

As I have repeatedly said on this blog, you can’t get a healthy economy without a healthy banking system. And a healthy banking system implies generating return around the cost of capital. It does not imply bashing banks and trying to transform them regardless of the consequences over a fifteen-year period.

In an effort to strengthen the banking system’s balance sheet and punish bankers for their alleged past behaviour, policymakers have forgotten the most important component of the system, without which there is no bank in the first place: the shareholder.

Without shareholder, no private enterprise. And banks are starting to bleed shareholders.

*To be fair, a few regulators have been complaining about the lack of coordination between regulatory agencies:

I am trying to build capital in firms, and it is draining out down the other side.

Empirical evidence of Basel’s capital misallocation

Some old-time readers perhaps remember what I called the ‘RWA-based ABCT’ (RWA for risk-weighted asset, and ABCT for Austrian Business Cycle Theory). RWAs, defined by Basel banking rules, represent the capital ‘price’ of each asset class held on a bank’s balance sheet. The classic ABCT represents a monetary policy-induced boom, during which interest rates are below their natural rate, misleading entrepreneurs into believing that borrowing for long-term projects will pay off. But, as savings haven’t actually increased, there is an intertemporal discoordination between entrepreneurs and savers’ expectations, leading to systemic misallocation of capital, eventually resulting in a bust as projects cannot be completed or turn out to be loss-making.

I have always argued that a regulation-induced boom could also trigger a relatively similar capital misallocation and boom-bust cycle. To sum up, Basel rules have fixed bank’s capital price low for a number of asset classes (which all boomed over the decade before the financial crisis, coincidentally…) and high for some others (which have been chronically starved of funds, coincidentally…). One of these asset classes that were deemed risky enough to get penalized by regulators is also one of the most crucial for the economy: SME and business lending.

I was recently made aware of two different papers actually criticising this Basel framework for being too harsh and unnecessarily harming SMEs. One of them, published last October by Bams, Pisa and Wolff, studied the US market and is titled Credit Risk Characteristics of US Small Business Portfolios (see the related VoxEU article here, or a pdf presentation summary here).

They find (incredibly important paragraph; read it twice, or perhaps three times if necessary):

that small businesses are subject to inefficient capital allocations imposed by the regulator. The results show significant discrepancies in capital requirements implied by Basel II and the proposed model. For all levels of credit worthiness of the obligor, the Basel II formula significantly overstates the asset correlations and thus the capital requirements for sub-portfolios of small businesses, which is shown by the highly significant paired difference test. Indeed, we observe that the capital requirement is on average almost four times higher than the data suggest. And it is the more creditworthy obligors that suffer the highest capital charges relative to their riskiness. For these firms the regulatory formula overestimates the capital requirement even by factor of about ten. As a result these more creditworthy obligors pay for the credit risk of their less creditworthy peers. It also creates inverse incentives for financial institutions, which may flee to other obligor classes in which loans originated are less costly to hold.

Now just try to imagine the cost that Basel has been to our economy… They also find that large corporate benefits from more relax capital requirements relative to SMEs. Although I have to add that even large corporates are inefficiently penalised relative to some other exposure types such as real estate and sovereign. Therefore, the capital treatment differential between SMEs and real estate is very large. It shows the secular stagnation story into a different perspective.

But that’s not it. An older (2013) Deutsche Bundesbank piece of research that I wasn’t aware of also found remarkably similar results in Germany (Evaluation of minimal capital requirements for bank loans SMEs, by Dullmann and Koziol).

They do acknowledge that RWAs affect banks’ profitability, and hence capital allocation:

Since regulatory capital requirements can affect the interest margins required by the lender, only their appropriate calculation in the sense that they reflect the actual risk posed by the borrower will ensure an optimal credit supply for the economy. Since SMEs are the backbone of the economy in many countries, such as Germany, appropriate capital requirements are crucial for economic growth.

After looking at a portfolio of German firms and their default rates, they estimate the asset correlation, and therefore potential capital buffer that would be required to absorb unexpected losses of a portfolio of such firms. They come up with a number of tables (such as the one below) showing the capital requirements differences between their estimates and Basel’s requirements.

As in the US, they found that Basel systematically overestimate the capital required to absorb SME-linked losses.

They conclude:

In our paper we have identified two cases in which our empirical results suggest that the relative differences between the capital requirements for large corporates and those for SMEs (in other words, the capital relief for SMEs) are lower in the current regulatory framework than implied by our empirically estimated asset correlations. Since these average total differences reflect the capital relief granted for SMEs by the regulators they may indicate { in certain cases and if taken at face value { a potential for increasing this capital relief. This would be equivalent to lowering the regulatory capital requirements for SMEs, for instance by lowering the asset correlation values in the IRBA formula or by lowering the RSA risk weights directly.

In short, we now seem to have empirical evidence that the Basel ruleset leads to a systemic inefficient capital allocation across the economy, with a number of sectors unnecessarily suffering (and others booming instead). Of course the results of those two studies might not apply to all countries that have implemented Basel. But the US is the largest economy in the world, and Germany the largest in Europe, so any misallocation of capital has much broader repercussions.

HT: Stefanie Schulte

The ‘run on repo’ is only part of the recession story

In my latest post I wrote that the Gorton story of the Great Recession (i.e. run on repo) was at best far from comprehensive and misleading. It only applies to a small portion of the financial sector, that is a number of broker-dealers, large banks and some shadow banks that made extensive use of (mostly short-term) reverse repos as investments and repos as funding sources.

While this run did occur, saying that it was the cause of the crisis is like saying that traditional bank runs were what triggered financial crises of the past. It is inaccurate: runs are mostly symptoms, albeit symptoms that can aggravate the underlying conditions. The Gorton story hides everything else that happened before and after the onset of the crisis, and which mostly impacted smaller banks and investors that were not making extensive use of repos. While some of those failing institutions did suffer from risk-aversion in the wholesale market, threatening to make them illiquid, many deposit-funded banks did not collapse because their funding source dried up. They collapsed because their capital evaporated.

A very recent paper by Adonis Antoniades, titled Commercial Bank Failures During The Great Recession: The Real (Estate) Story, confirms this view. This is Antoniades:

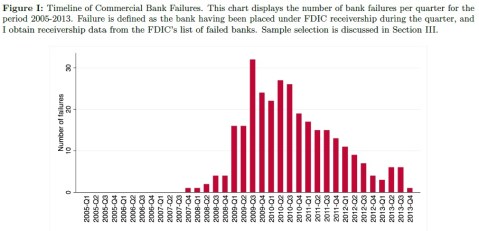

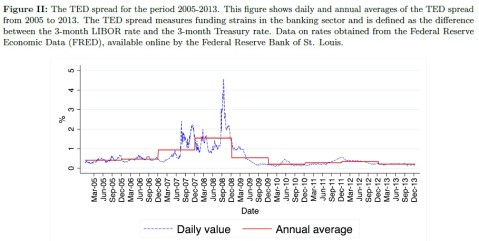

The main determinants of balance sheet stress for commercial banks were much different than those for brokers-dealers. Though aggregate funding strains have been identified as one of the precipitating causes of the crisis, with a particularly pronounced impact on brokers-dealers, funding conditions alone cannot explain commercial bank failures. The FDIC reported 492 bank failures from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2013. However, the vast majority of these failures – 462 failures – took place after the last quarter of 2008. That is, during a period when aggregate funding pressures in the banking sector had completely abated. Furthermore, throughout the financial crisis commercial banks had access to lender of last resort facilities at the Federal Reserve’s discount window.

Well, there is still a stigma associated to any central bank borrowing, but the rest of his point is valid. He provides the following US bank failures timeline:

As well as the TED spread over a long time period:

Essentially, he finds no evidence that US banks increased their exposures to traditional home mortgages or agency (i.e. Fanny and Freddy) MBS products in the few years preceding the crisis, and that this was mostly due to securitisation. But he did find that banks increased their exposure to all other real estate product categories. Overall, US banks “moved towards a more real estate-focused product mix during this period.” This is broadly consistent with Jorda et al’s research that I have mentioned here a number of times, although their research focused on aggregate real estate credit.

He then finds no or low correlation between traditional household mortgages and risk of bank failures, but significant correlation with commercial real estate lending:

The real estate risk that mattered most for bank failures was indeed primarily non-household. Neither exposure to traditional home mortgages nor to agency MBS increased the probability of failure over and above the base effect of non-real estate exposures in the illiquid assets and marketable securities portfolios, respectively. The probability of bank failure also increased with holdings of private-label MBS, but only for larger banks. Non-household real estate products – both loans and credit lines – on the other hand, enter with positive, economically and statistically significant coefficients.

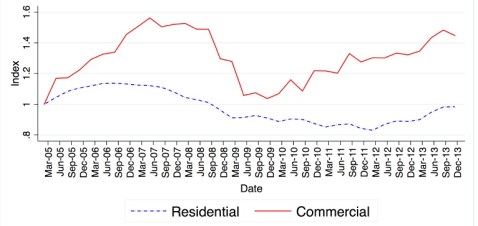

It isn’t that surprising as the CRE market boomed and collapsed with greater fluctuation than the residential market (see chart below for the US). Similar patterns can be found in the UK, Spain and other countries.

He provides an explanation as to why traditional mortgage exposures still remain critical for the financial system as a whole:

The estimated coefficient for the effect of holdings of traditional home mortgages, should not be read as suggesting that there were no significant losses during the crisis stemming from exposure to this asset category. Rather, together with the earlier observations on the accumulation of real estate risk during the run-up to the crisis, these results suggest that commercial banks off-loaded part of that particular risk to other types of financial intermediaries through the securitisation channel. And, possibly, that they adequately provisioned capital for the residual risk associated with home mortgage loans retained on-balance sheet. The absence of an effect for holdings of agency MBS is likely driven by agency and (implicit) government guarantees associated with these securities, but also by the significant support that this market received through a number of Federal Reserve interventions.

Moreover, banks that increased their exposure to non-household mortgage products more rapidly than average were more likely to fail.

Finally, this chart of Antoniades’ paper demonstrates the importance of bank accounting standards. Look at the quick price fall, and then rise, of private-label MBSs. A firm with heavy exposure to this asset class would see its capital disappear almost overnight due to the rapidly collapsing prices. But wait a few months that prices recover and the same firm might well have survived. This has important consequences for financial stability, bank lending and hence money supply growth and monetary policy transmission.

Recent Comments