Negative interest rates and free banking

Is the universe about to make a switch to antimatter? Interest rates in negative territory is the new normal. Among regions that introduced negative rates, most have only put them in place on deposit at the central bank (like the -0.2% at the ECB for instance). Sweden’s Riksbank is innovating with both deposit and repo rates in negative territory. It now both has to pay banks that borrow from it overnight and… charge commercial banks that deposit money with it, like a mirror image of the world we used to know. However, like antimatter and matter and the so-called CP violation (which describes why antimatter has pretty much disappeared from the universe), positive rates used to dominate the world. Until today.

Many of those monetary policy decisions seem to be taken in a vacuum: nobody seems to care that the banking regulation boom is not fully conductive to making the banking channel of monetary policy work (and bankers are attempting to point it out, but to no avail). In some countries, those decisions also seem to be based on the now heavily-criticised inflation target, as CPI inflation is low and central bankers try to avoid (whatever sort of) deflation like the plague.

As I described last year with German banks, negative rates have….negative effects on banks: it further amplifies the margin compression that banks already experience when interest rates are low by adding to their cost base, and destabilise banks’ funding structure by providing depositors a reason to withdraw, or transfer, their deposits. Some banks are now trying to charge some of their largest, or wealthiest, customers to offset that cost. At the end of the day, negative rates seem to slightly tighten monetary policy, as the central bank effectively removes cash from the system.

It is why I was delighted to read the below paragraphs in the Economist last week, a point that I have made numerous times (and also a point that many economists seem not to understand):

In fact, the downward march of nominal rates may actually impede lending. Some financial institutions must pay a fixed rate of interest on their liabilities even as the return on their assets shrivels. The Bank of England has expressed concerns about the effect of low interest rates on building societies, a type of mutually owned bank that is especially dependent on deposits. That makes it hard to reduce deposit rates below zero. But they have assets, like mortgages, with interest payments contractually linked to the central bank’s policy rate. Money-market funds, which invest in short-term debt, face similar problems, since they operate under rules that make it difficult to pay negative returns to investors. Weakened financial institutions, in turn, are not good at stoking economic growth.

Other worries are more practical. Some Danish financial firms have discovered that their computer systems literally cannot cope with negative rates, and have had to be reprogrammed. The tax code also assumes that rates are always positive.

In theory, most banks could weather negative rates by passing the costs on to their customers in some way. But in a competitive market, increasing fees is tricky. Danske Bank, Denmark’s biggest, is only charging negative rates to a small fraction of its biggest business clients. For the most part Danish banks seem to have decided to absorb the cost.

Small wonder, then, that negative rates do not seem to have achieved much. The outstanding stock of loans to non-financial companies in the euro zone fell by 0.5% in the six months after the ECB imposed negative rates. In Denmark, too, both the stock of loans and the average interest rate is little changed, according to data from Nordea, a bank. The only consolation is that the charges central banks levy on reserves are still relatively modest: by one estimate, Denmark’s negative rates, which were first imposed in 2012, have cost banks just 0.005% of their assets.

Additionally, a number of sovereign, and even corporate, bonds yields have fallen (sometimes just briefly) into negative territory, alarming many financial commentators and investors. The causes are unclear, but my guess is that what we are seeing is the combination of unconventional monetary policies (QE and negative rates) and artificially boosted demand due to banking regulation (and there is now some evidence for this view as Bloomberg reports that US banks now hoard $2Tr of low-risk bonds). Some others report that supply is also likely to shrink over the next few years, amplifying the movement. There are a few reasons why investors could still invest in such negative-yielding bonds however.

As Gavyn Davies points out, we are now more in unknown than in negative territory. Nobody really knows how low rates can drop and what happens as monetary policy (and, I should add, regulation) pushes the boundaries of economic theory. At what point, and when, will economic actors start reacting by inventing innovative low-cost ways to store cash? The convenience yield of holding cash in a bank account seems to be lower than previously estimated, although it is for now hard to precisely estimate it as only a tiny share of the population and corporations is subject to negative rates (banks absorb the rest of the cost). The real test for negative rates will occur once everyone is affected.

Free markets though can’t be held responsible for what we are witnessing today. As George Selgin rightly wrote in his post ‘We are all free banking theories now’, what we currently experience and the options we could possibly pick have to measure up against what would happen in a free banking framework.

Coincidentally, a while ago, JP Koning wrote a post attempting to describe how a free banking system could adapt to a negative interest rates environment. He argued that commercial banks faced with negative lending rates would have a few options to deal with the zero lower bound on deposit rates. He came up with three potential strategies (I’ll let you read his post for further details): remove cash from circulation by implementing ‘call’ features, cease conversion into base money, and penalize cash by imposing through various possible means what is effectively a negative interest rate on cash. I believe that, while his strategies sound possible in theory, it remains to be seen how easy they are to implement in practice, for the very reason that the Economist explains above: competitive forces.

But, more fundamentally, I think his assumptions are the main issue here. First, the historical track record seems to demonstrate that free banking systems are more stable and dampen economic and financial fluctuations. Consequently, a massive economic downturn would be unlikely to occur, possibly unless caused by a massive negative supply shock. Even then, the results in such economic system could be short-term inflation, maintaining nominal (if not real) interest rates in positive territory.

Second (and let’s leave my previous point aside), why would free banks lend at negative rates in the first place? This doesn’t seem to have ever happened in history (and surely pre-industrial rates of economic growth were not higher than they are now, i.e. ‘secular stagnation’) and runs counter to a number of theories of the rate of interest (time preference, liquidity preference, marginal productivity of capital, and their combinations). JPK’s (and many others’) reasoning that depositors wouldn’t accept to hold negative-yielding deposits for very long similarly applies to commercial banks’ lending.

Why would a bank drop its lending rate below zero? In the unrealistic case of a bank that does not have a legacy loan book, bankers would be faced by two options: lend the money at negative rates, during an economic crisis with all its associated heightened credit and liquidity risk, or keep all this zero-yielding cash on its balance sheet and make a loss equivalent to its operating costs. If a free bank is uncertain to be able to lower deposit rates below lending rates, better hold cash, make a loss for a little while, the time the economic crisis passes, and then increase rates again. This also makes sense in terms of competitive landscape. A bank that, unlike its competitors, decides to take a short-term loss without penalising the holders of its liabilities is likely to gain market shares in the bank notes (and deposits) market.

Now, in reality, banks do have a legacy loan book (i.e. ‘back book’) before the crisis strike, a share of which being denominated at fixed, positive, nominal interest rates. Unless all customers default, those loans will naturally shield the bank from having to take measures to lower lending rates. The bank could merely sit on its back book, generating positive interest income, and not reinvest the cash it gets from loan repayments. Profits would be low, if not negative, but it’s not the end of the world and would allow banks to support their brand and market share for the longer run*.

Finally, the very idea that lending rates (on new lending, i.e. ‘front book’) could be negative doesn’t seem to make sense. Even if we accept that the risk-free natural rate of interest could turn negative, once all customer-relevant premia are added (credit and liquidity**), the effective risk-adjusted lending rate is likely to be above the zero bound anyway. As the economic crisis strikes, commercial banks will naturally tend to increase those premia for all customers, even the least risky ones. Consequently, a bank that lent to a low-risk customer at 2% before the crisis, could well still lend to this same customer at 2% during the crisis (if not higher), despite the (supposed) fall of the risk-free natural rate.

I conclude that it is unlikely that a free banking system would ever have to push lending (or even deposit) rates in negative territories, and that this voodoo economics remains a creature of our central banking system.

*Refinancing remains an option for borrowers though. However, in crisis times, it’s likely that only the most creditworthy borrowers would be likely to refinance at reasonable rates (which, as described above, could indeed remain above zero)

**Remember this interest rate equation that I introduced in a very recent post:

Market rate = RFR + Inflation Premium + Credit Risk Premium + Liquidity Premium

Photo: MIT

Pushing market rationality too far

In a new post on Switzerland, Scott Sumner said (my emphasis):

The following graph shows that the SF has fallen from rough parity with the euro after the de-pegging, to about 1.08 SF to the euro today:

And this graph shows that the Swiss stock market, which crashed on the decision that some claimed was “inevitable” (hint, markets NEVER crash on news that is inevitable), has regained most of its losses.

I often enjoy what Scott Sumner writes, but this comment is from someone who doesn’t understand, or has no experience in, financial markets. We all know that Sumner strongly believes in rational expectations and the EMH. But this is pushing market efficiency and rationality too far.

According to Sumner, “markets never crash on news that is inevitable”. Really? Is he saying that markets believed the Euro peg would remain in place forever (which is the only necessary condition for the de-pegging not being ‘inevitable’)?

In reality many investors, if not most (though it can’t be said with certainty), were aware that the peg would be removed and of the resulting potential consequences for Swiss companies. So why the crash?

While investors surely knew that the peg wouldn’t last, they didn’t know when it would end. They were acting on incomplete information. However, this is perhaps what Sumner implies: the Swiss central bank should have provided markets with a more precise statement of when, and in what conditions, the peg would end. Markets would have revised their expectations and priced in the information. This reasoning underpins the rationale for monetary policy rules and forward guidance. But in practice, providing ‘guidance’ isn’t easy: central bankers are not omniscient, have imperfect access to information and cannot accurately forecast the future in an ever-changing world. See what happened to the BoE’s forward guidance policy, which ended up not being much guidance at all as central bankers changed their minds as the economic situation in the UK evolved*.

But the rational expectations argument itself can be used to describe many different situations. If investors believe the peg will end at some point, but don’t know exactly when, it is arguably as ‘rational’ for them to try to maximise gains as long as they could and to try to exit the market just before it crashes, as it is ‘rational’ to adapt their positions to minimise their risk exposure. When the market finally does crash, it often overshoots, for the same reason: benefiting from a short-term situation to maximise profits.

Taking advantage of monetary policy is what traders do. It is their job. Of course, many will fail in their attempt. But necessarily identifying rational expectations with strong short-term risk-aversion and immediate inclusion of external information into prices is abusive.

This latest Bloomberg article shows that close to 20% of traders expect the Fed to raise rates in June, and consequently have surely put in place trading strategies around this belief, and are likely to react negatively if their expectations aren’t fulfilled. However, who doubts that a rate rise is ‘inevitable’? This demonstrates the price-distorting ability of central banks. In order to limit extreme price fluctuations and crashes, the better central banks can do is to disappear from the marketplace entirely.

*Other practical restrictions on guidance include the fact that, while professional investors are likely to be aware of their significance, the rest of the population has no idea what the hell you’re talking about, if it has even heard of it. As a result, the efforts the BoE made to reassure UK borrowers that rates would not rise in the short-run seemed pointless, as virtually no average Joe got it, implying that most people didn’t change their borrowing behaviour/plan in consequence.

I have made a case for rule-based policies a while ago, which I do believe would limit distortions to an extent.

Crush RWAs to end secular stagnation?

Some BIS researchers very recently published this piece of research demonstrating that the growth of the financial sector was linked to lower productivity in the economy. MCK in FT Alphaville commented on it and reached the wrong conclusion (the title of his post is ‘Crush the financial sector, end the great stagnation?’, though he could be forgiven given that the BIS paper itself is titled ‘Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?’).

I have attempted in previous posts to explain why Basel risk-weighted assets (RWAs) were the root cause of the misallocation of bank credit and hence the misallocation of capital in the economy prior to the financial crisis: in order to optimise return on equity, bankers were incentivised by RWAs to allocate a growing share of available loanable funds to the real estate sector, creating an unsustainable boom. I also speculated that, consequently, fewer financial resources were hence available for sectors that were penalised by regulatory-defined high RWAs (i.e. business lending), and that this could be one of the main causes of the so-called ‘secular stagnation’.

I have also regularly criticized governments’ and central banks’ schemes such as FLS and TLTRO when they were announced, as they could simply not address the fundamental problem that Basel had introduced a few decades earlier.

I have recently pointed out that new studies seem to highlight that, indeed, real estate lending had overtaken business lending for the first time in the past 150 years exactly after Basel 1 was put in place at the end of the 1980s, and that the growth of business lending had been lower since then. (Same chart again. Yes it is that important)

This new BIS study is remarkably linked, although its authors don’t seem to have noticed. This is what they conclude:

In our model, we first show how an exogenous increase in financial sector growth can reduce total factor productivity growth. This is a consequence of the fact that financial sector growth benefits disproportionately high collateral/low productivity projects. This mechanism reflects the fact that periods of high financial sector growth often coincide with the strong development in sectors like construction, where returns on projects are relatively easy to pledge as collateral but productivity (growth) is relatively low. […]

First, at the aggregate level, financial sector growth is negatively correlated with total factor productivity growth. Second, this negative correlation arises both because financial sector growth disproportionately benefits to low productivity/high collateral sectors and because there is an externality that creates a possible misallocation of skilled labour.

Replace some of the terms above with RWAs and you get the right picture. What those researchers miss is that the growth of the financial sector has been similar in previous periods over the past 150 years, with no decline in secular growth rate and productivity. However, what changed since the 1980s is the allocation of this growth. And the dataset this BIS piece examines only starts…in 1980. Their conclusion that high collateral industries would attract a higher share of lending is also coherent with my views, as higher lending collateralisation reduces the required capital buffer than banks need to maintain.

MCK is right when he declares that

the growth of the financial sector has been concentrated in mortgage lending, which means that more lending usually just leads to more building. That’s a problem for aggregate productivity, since the construction industry is one of the few that has consistently gotten less productive over time. For example, Spain had no productivity growth between 1998 and 2007, a period when 20 per cent of all the net job growth can be attributed to the building sector.

But his conclusion that regulation needs to force the banking industry to get smaller is off the mark. Getting rid of the incentives created by RWAs, and the resulting unproductive misallocations, is what is needed.

Central banks don’t/do/don’t/do control interest rates

Ben Southwood and I agree on most things but a few topics. Whether central banks’ decisions affect interest rates is one of those, though I do think we have more common than we’re willing to admit. Here are the various reasons that convince me that central banks exert a relatively strong influence on most market rates.

On ASI’s blog, Ben wrote a piece about a 2013 research paper from Fama, who looked into interest rate time series to determine whether or not the Fed controlled interest rates. According to Ben’s own interpretation of the paper, the answer is ‘probably not’. Ironically, my take is completely different.

Throughout most of his paper, Fama’s results do indicate that the Fed exercises a relatively firm grip on all sorts of interest rates, as he admits it himself many times. For example, in his conclusion he writes:

A good way to test for Fed effects on open market interest rates is to examine the responses of rates to unexpected changes in the Fed’s target rate. Table 5 confirms that short-term rates (the one month commercial paper rate and three-month and six-month Treasury bill rates), respond to the unexpected part of changes in TF. Table 5 is the best evidence of Fed influence on rates, and event studies of this sort are center stage in the active Fed literature.

But I find Fama a little biased as he always tries to defend his original position that the Fed does not exert such a strong control:

But skeptics have a rejoinder. The response of short rates to unexpected changes in the Fed’s target rate might be a signaling effect. Rates adjust to unexpected changes in TF because the Fed is viewed as an informed agent that sets TF to line up with its forecasts of how market forces will shape open market rates.

Or also:

The Table 4 evidence that short-term interest rates forecast changes in the Fed funds target rate is not news (Hamilton and Jorda 2002). For those who believe in a powerful Fed, the driving force is TF, the concrete expression of Fed interest rate policy, and the forecast power of short rates simply says that rates adjust in advance to predictable changes in the Fed’s target rate. (See, for example, Taylor 2001.) The evidence is, however, also quite consistent with a passive Fed that changes TF in response to open market interest rates. There are, of course, scenarios in which both forces are at work, possibly to different extents at different times. The Fed may go passive and let the market dictate changes in TF when inflation and real activity are satisfactory, but turn active when it is dissatisfied with the path of inflation or real activity. This mixed story is also consistent with the evidence in Table 3 that the Fed funds rate moves toward both the open market commercial paper rate and the Fed’s target rate.

However Fama never explains why the Fed would simply passively change its base rate in response to private markets. This seems to defeat the purpose of having an active monetary policy.

In short, most of the evidences that Fama finds seem to demonstrate that the Fed indeed does control most interest rates to an extent (in particular short-term ones). But he does not seem to accept his own result and tries to come up with alternative explanations that are less than convincing, to say the least. He concludes by basically saying that…we cannot come to a conclusion.

But Fama’s paper suffers from a major flaw. Let’s break down a market interest rate here:

Market rate = RFR + Inflation Premium + Credit Risk Premium + Liquidity Premium

Fama’s dataset wrongly runs regressions between Fed’s base rate movements and observable market yields on some securities. The rate that the Fed influences is the risk free rate (RFR). But as seen above, market rates contain a number of premia that vary with economic conditions and the type of security/lending and on which the Fed has limited control.

For instance, when a crisis strikes, the credit risk premium is likely to jump. In response, the Fed is likely to cut its base rate, meaning the RFR declines. But the observable rate does not necessarily follow the Fed movement. It all depends on the amplitude of the variation in each variable of the equation above. Hence the correlation will only provide adequate results if the economic conditions are stable, with no expected change in inflation or credit risk. Does this imply that the Fed has no control over the interest rate? Surely not, as the RFR it defines is factored in all other rates. In the example above, the market rates ends up lower than it would have normally been if fully set by private markets.

David Beckworth had a couple of interesting charts on its blog, which attempted to strip out premia from the 10-year Treasury yield (it’s not fully accurate but better than nothing):

Now compare the 1990-2014 non-adjusted and adjusted 10-year Treasury yield with the evolution of the Fed base rate below:

The shapes of the adjusted 10-year yield and the Fed funds rate curves are remarkably similar, whereas this isn’t the case for the unadjusted yield*. Yet most of Fama’s argument about the Fed having a limited influence on long-term rates rests on his interpretation of the evolution of the spread between the Fed funds target rate and the unadjusted 10-year yield.

(the same reasoning applies to commercial paper spread, though the inflation premium is close to nil in such case)

Second, I find it hard to understand Ben’s point that markets set rates, when central banks’ role is indeed to define monetary policies and, by definition, impact those market rates. If only markets set rates, then surely it is completely pointless to have central banks that attempt to control monetary policies through various tools, including the control on the quantity of high-powered money. In a simple loanable funds model (let’s leave aside the banking transmission mechanism), in which the interest rate is defined by the equilibrium point between supply and demand for loanable funds, it is quite obvious that a central bank injecting, or removing, base money from the system (that is, pushing the supply curve one way or another) will affect the equilibrium rate. Of course the central bank does not control the demand curve. But the fact that the bank does not have a total control over the interest rate does not imply that it has none and that its policies have no effect. What does count is that the resulting equilibrium rate differs from the outcome that free markets would have produced.

I am also trying to get my head around what I perceive as a contradiction here (I might be wrong). Market monetarists (of whom Ben seems to belong) believe that money has been ‘tight’ throughout the recession due to central banks’ misguided monetary policies. They seem to think that rates would have dropped much faster in a free market. This seems to demonstrate that market monetarist believe in the strong influence of central banks on many rates. But according to Ben, central banks do not have much influence on rates. Does he imply that free markets were responsible for the ‘tight’ policy that followed the crisis?

So far in this post we’ve only seen cases in which the central bank indirectly affects market rates. But some markets are linked to the central bank base rate from inception. For instance, in the UK, most mortgage rates (‘standard variable rates’) are explicitly and contractually defined as ‘BoE Base Rate + Margin’**. The margin rarely changes after the contract has been agreed. Any change in the BoE rate ends up being automatically reflected in the rate borrowers have to pay (that is, before banks are all forced to widen the contract margin because of the margin compression phenomenon, as I described in my previous exchange with Ben here and here). The only effect of banking competition is to lead to fluctuations of a few bp up or down on newly originated mortgages (i.e. one bank offers you BoE + 1.5% and another one BoE + 1.3%).

At the end of the day, I have the impression that a part of our disagreement is merely due to semantics. I don’t think anybody has declared that central banks fully control rates. This would be foolish. But they certainly exert a strong influence (at least) through the risk-free rate, and this reflects on all other rates across maturities and risk profiles.

*To be fair, it does look like some of the Fed’s decisions were anticipated by markets and reflected in Treasury yields just before the target rate was changed.

**In some other countries the link is looser, as the central bank rate is replaced by the local interbank lending rate (Libor, Euribor…).

McKinsey on banking and debt

A recent report by the consultancy McKinsey highlights how much the world has not deleveraged since the onset of the financial crisis. Many newspapers have jumped on the occasion to question whether or not the policies adopted since the crisis were the right ones (FT, Telegraph, The Economist…). This is how the total stock of debt has evolved since 2000:

As the following chart shows, the vast majority of countries saw their overall level of debt increase:

As the following chart shows, the vast majority of countries saw their overall level of debt increase:

McKinsey affirms that “household debt continues to grow rapidly, and deleveraging is rare”, and that the same broadly applies to corporate debt. China is an extreme case: total debt level, as a share of GDP, grew from 121% of GDP in 2000, to 158% in 2007 to…282% at end-H114. And growing.

McKinsey affirms that “household debt continues to grow rapidly, and deleveraging is rare”, and that the same broadly applies to corporate debt. China is an extreme case: total debt level, as a share of GDP, grew from 121% of GDP in 2000, to 158% in 2007 to…282% at end-H114. And growing.

Unsurprisingly, household debt is driven by mortgage lending (including in China). It isn’t a surprise to see house prices increasing in so many countries. How this is a reflection that we currently are in a sustainable recovery, I can’t tell you. How this is a signal that monetary policy has been ‘tight’, I can’t tell you either. If monetary policy has indeed been ‘tight’, then it shows the power of Basel regulation in transforming a ‘tight’ monetary policy into an ‘easy’ one for households through mortgage lending. How this total stock of debt will react when interest rates start rising is anyone’s guess…

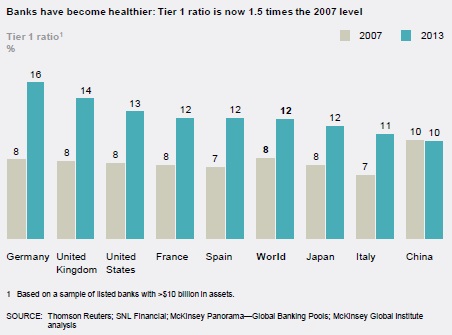

McKinsey’s claim that “banks have become healthier” is questionable at best, as they use regulatory Tier 1 ratios as a benchmark. Indeed a lot of banks have boosted their Tier 1 ratio by reducing RWA density (i.e. the average risk-weight applied to their assets) rather than actually raising or internally generating extra capital.

As expected given how capital intensive corporate lending has become thanks to our banking regulatory framework, and in line with recent research, banks are now mostly funding households at the expense of businesses:

As expected given how capital intensive corporate lending has become thanks to our banking regulatory framework, and in line with recent research, banks are now mostly funding households at the expense of businesses:

McKinsey highlights that P2P lending, while still small in terms of total volume, doubles in size every year, and is mostly present in China and the US.

And in fact, in another article, McKinsey explains that the digital revolution is going to severely hit retail banking. I have several times described that banks’ IT systems were on average out-of-date, that this weighed on their cost efficiency and hence profitability, and that it even possibly impaired the monetary policy transmission channel. I also said that banks needed to react urgently if they were not to be taken over by more recent, more efficient, IT-enabled competitors. A point also made in The End of Banking, according to which technology allows us to get rid of banks altogether.

McKinsey is now backing up those claims with interesting estimates. According to the consultancy, and unsurprisingly, operating costs would be the main beneficiary of a more modern IT framework:

McKinsey goes as far as declaring that:

McKinsey goes as far as declaring that:

The urgency of acting is acute. Banks have three to five years at most to become digitally proficient. If they fail to take action, they risk entering a spiral of decline similar to laggards in other industries.

Unfortunately, current extra regulatory costs and litigation charges are making it very hard for banks to allocate any budget to replace antiquated IT systems.

If banks already had those systems in place as of today, I would expect to see lending rates declining further – in line with monetary policy – across all lending products as margin compression becomes less of an issue. In a world where banks have zero operating cost, its net interest income doesn’t need to be high to generate a net profit.

In the end, regulators are shooting themselves in the foot: not only new regulations and continuous litigations may well have the effect of facilitating new non-banking firms’ takeover of the financial system, but also monetary policy cannot have the effect that regulators/central bankers themselves desire.

Are ETFs and activist investors redefining the agency theory?

I wrote a few weeks ago that the rise of ETF might, in the end, make markets less efficient. While I still believe this to be a likely effect, The Economist just gave me a reason for hope. In two articles (here and here), the newspaper observes the parallel rise of activist investors.

The Economist adds another reason to my list of potentially negative effects of ETFs on financial markets: corporate governance. Indeed, not only buying indices raises the share price of all firms (good and bad) across a given portfolio, reducing the information contained in prices, but also ETFs are the most informal investors ever. They passively replicate the market and do not intervene in firms’ management. Underperforming managers consequently benefit from: 1. the value of their firm evolving in line with better-performing peers, and 2. not being questioned by demanding shareholders.

The Economist adds another reason to my list of potentially negative effects of ETFs on financial markets: corporate governance. Indeed, not only buying indices raises the share price of all firms (good and bad) across a given portfolio, reducing the information contained in prices, but also ETFs are the most informal investors ever. They passively replicate the market and do not intervene in firms’ management. Underperforming managers consequently benefit from: 1. the value of their firm evolving in line with better-performing peers, and 2. not being questioned by demanding shareholders.

Thankfully, this remains an imaginary world (at least for now), as some investors (mostly hedge funds) have decided to take a more active stance. Those activists take a small stake in the company and lobby other, more passive, investors to join them in their quest for sometimes radical changes in the firm’s structure. As I pointed out when hedge funds took over the UK-based Cooperative Bank, conventional wisdom depicts them as corporate vultures seeking short-term gains at the expense of the long-term health of the firms they invest in. But I also mentioned this study, which couldn’t be clearer in dispelling those common myths:

Starting with operating performance, we find that operating performance improves following activist interventions and there is no evidence that the improved performance comes at the expense of performance later on. During the third, fourth, and fifth year following the start of an activist intervention, operating performance tends to be better, not worse, than during the pre-intervention period. Thus, during the long, five-year time window that we examine, the declines in operating performance asserted by supporters of the myopic activism claim are not found in the data. We also find that activists tend to target companies that are underperforming relative to industry peers at the time of the intervention, not well-performing ones.

For sure, not all activists are beneficial. But to maximise the value of their stake, activists need to convince other potential investors that the longer-term operating performance of the firm has indeed been improved (which should reflect in the investment’s expected future cash flows). As we say, “you can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.” While Gordon Gekko’s ‘Greed is Good’ speech might enrage some, it does contain a fundamental corporate governance truth. If activists on aggregate damaged companies’ prospects, the value of their stake would plummet and they would run out of business. As The Economist reports:

Activists point out that if they were to propose changes that clearly damaged a firm’s prospects the stock price would fall. “Unless you have one eye on the long term—how customers and products are affected—you will not succeed,” says Mr Loeb.

In short, financial markets are becoming increasingly polarised between two trends situated at almost the opposite side of the investing spectrum: on the one hand, conventional investors pile into cheaper but ‘dumb’ and passive index funds; on the other hand, very active shareholders get their hands dirty fighting to improve the operations of underperforming firms. This is welcome and reassuring, and provides further evidence that markets can spontaneously correct themselves when required and when there is the opportunity to do so.

This also represents a corporate governance paradigm change. Conventional agency theory states that, due to asymmetric information, managers may not always act in the best interest of shareholders. The theory also implies that shareholders aren’t actively involved in operational decisions. But activist investors turn the theory on its head. As a result, the new agency theory relies on a small number of activist investors (agents) taking the right strategy decisions for hundreds or thousands of other passive investors/ETFs (principals). I would argue that, while imperfect, this new version of the agency theory is more likely to work as agents’ and principals’ interests are naturally more aligned.

Cachanosky on the productivity norm, Hayek’s rule and NGDP targeting

Nicolas Cachanosky and I should get married (intellectually, don’t get overexcited). Some time ago, I wrote about his very interesting paper attempting to start the integration of finance and Austrian capital theories. A couple of weeks ago, I discovered another of his papers, published a year ago, but which I had completely missed (coincidentally, Ben Southwood also discovered that paper at the exact same time).

Titled Hayek’s Rule, NGDP Targeting, and the Productivity Norm: Theory and Application, this paper is an excellent summary of the policies named above and the theories underpinning them. It includes both theoretical and practical challenges to some of those theories. Cachanosky’s paper reflects pretty much exactly my views and deserved to be quoted at length.

Cachanosky defines the productivity norm as “the idea that the price level should be allowed to adjust inversely to changes in productivity. […] In other words, money supply should react to changes in money demand, not to changes in production efficiency.” Referring to the equation of exchange, he adds that “because a change in productivity is not in itself a sign of monetary disequilibrium, an increase in money supply to offset a fall in P moves the money market outside equilibrium and puts into motion an unnecessary and costly process of readjustment”, which is what current central bank policies of price level targeting do. The productivity norm allows mild secular deflation by not reacting to positive ‘real’ shocks.

He goes on to illustrate in what ways Hayek’s rule and NGDP targeting resemble and differ from the productivity norm:

There are instances where the productivity norm illuminated economists that talked about monetary policy. Two important instances are Hayek during his debate with Keynes on the Great Depression and the market monetarists in the context of the Great Recession. Both, Hayek and market monetarism are concerned with a policy that would keep monetary equilibrium and therefore macroeconomic stability. Hayek’s Rule and NGDP Targeting are the denominations that describe Hayek’s and market monetarism position respectively. Taking the presence of a central bank as a given, Hayek argues that a neutral monetary policy is one that keeps constant nominal income (MV) stable. Sumner argues instead that

“NGDP level targeting (along 5 percent trend growth rate) in the United States prior to 2008 would similarly have helped reduce the severity of the Great Recession.”

Hayek’s Rule of constant nominal income can be understood in total values or as per factor of production. In the former, Hayek’s Rule is a notable case of the productivity norm in which the quantity of factors of production is assumed to be constant. In the latter case, Hayek’s rule becomes the productivity norm. However, for NGDP Targeting to be interpreted as an application that does not deviate from the productivity norm, it should be understood as a target of total NGDP, with an assumption of a 5% increase in the factors of production. In terms of per factor of production, however, NGDP Targeting implies a deviation of 5% from equilibrium in the money market.

Cachanosky then highlights his main criticisms of NGDP targeting as a form of nominal income control, that is the distinction between NGDP as an ‘emergent order’ and NGDP as a ‘designed outcome’. He says that targeting NGDP itself rather than considering NGDP as an outcome of the market can affect the allocation of resources within the NGDP: “the injection point of an increase in money supply defines, at least in the short-run, the effects on relative prices and, as such, the inefficient reallocation of factors of production.” In short, he is referring to the so-called Cantillon effect, in which Scott Sumner does not believe. I am still wondering whether or not this effect could be sterilized (in a closed economy) simply by growing the money supply through injections of equal sums of money directly into everyone’s bank accounts.

To Cachanosky (and Salter), “NGDP level matters, but its composition matters as well.” He believes that targeting an NGDP growth level by itself confuses causes and effects: “that a sound and healthy economy yields a stable NGDP does not mean that to produce a stable NGDP necessary yields a sound and healthy economy.” He points out that the housing bubble is a signal of capital misallocation despite the fact that NGDP growth was pretty stable in pre-crisis years.

I evidently fully agree with him, and my own RWA-based ABCT also points to lending misallocation that would also occur and trigger a crisis despite aggregate lending growth remaining stable or ‘on track’ (whatever that means). I should also add that it is unclear what level of NGDP growth the central bank should target. See the following chart. I can identify many different NGDP growth ‘trends’ since the 1940s, including at least two during the ‘great moderation’. Fluctuations in the trend rate of US NGDP growth can reach several percentage points. What happens if the ‘natural’ NGDP growth changes in the matter of months whereas the central bank continues to target the previous ‘natural’ growth rate? Market monetarists could argue that the differential would remain small, leading to only minor distortions. Possibly, but I am not fully convinced. I also have other objections to NGDP level targeting (related to banking and transmission mechanism), but this post isn’t the right one to elaborate on this (don’t forget that I view NGDP targeting as a better monetary policy than inflation targeting but a ‘less ideal’ alternative to free banking or the productivity norm).

Cachanosky also points out that NGDP targeting policies using total output (Py in the equation of exchange) and total transactions (PT) do not lead to the same result. According to him “the housing bubble before 2008 crisis is an exemplary symptom os this problem, where PT increases faster than Py.”

Cachanosky also points out that NGDP targeting policies using total output (Py in the equation of exchange) and total transactions (PT) do not lead to the same result. According to him “the housing bubble before 2008 crisis is an exemplary symptom os this problem, where PT increases faster than Py.”

Finally, he reminds us that a 100%-reserve banking system would suffer from an inelastic money supply that could not adequately accommodate changes in the demand for money, leading to monetary equilibrium issues.

I can’t reproduce the whole paper here, but it is full of very interesting (though quite technical) details and I strongly encourage you to take a look.

Recent Comments