Basel capital requirements, labour reallocation and productivity

Last week I wrote two posts about recent research on the impact of Basel’s capital requirements on mortgage pricing and sovereign bond demand, which I believed were evidence of Basel enabling an ‘Austrian-type’ business cycle. Today, this is the last post of this mini-series, and it covers another great research report published by Claudio Borio and his team: Labour reallocation and productivity dynamics: financial causes, real consequences.

As often with Borio, this is a great paper. And it does seem to provide further evidence of Basel allowing distorted allocation of credit with dramatic economic consequences. However, I do need to point out that the paper does not explicitely point at Basel as the cause of the misallocation (but instead supposes that collateral availability plays a role). Rather, this is my own interpretation of it. The correlation looks pretty strong.

The paper looks at forty years of credit and productivity data across 20 advanced economies. It finds that

the decline in the allocation component during credit booms overwhelmingly reflects shifts in employment towards low productivity growth sectors. […] In other words, credit booms do not appear to affect the sectoral distribution of productivity gains, turning potentially high productivity growth sectors into low productivity growth ones. Rather, they induce labour shifts into lower productivity growth sectors. Productivity in industries with rapid long-run productivity growth does not grow any more slowly during credit booms, but these industries attract relatively fewer workers.

So credit booms and/or change in the allocation of credit do not alter the inherent productivity of each sector but rather shift labour between sectors. They also find that “labour reallocation is quantitatively the main channel through which credit booms affect productivity.” The key question being: which sectors benefit, and at the expense of which ones?

And here, the answer couldn’t be clearer (my emphasis):

The results suggest that manufacturing and construction are the two sectors primarily responsible for the slowdown. When either sector is withdrawn, the negative correlation goes away or at least weakens compared with the benchmark case. Interestingly, removing the financial sector does not affect our results.

Combining this result with the previous one, the conclusion is clear. Aggregate productivity slows down during credit booms primarily because employment expands more rapidly in the construction sector, which structurally features low productivity growth. And employment expands more slowly or contracts in manufacturing, which is structurally a high productivity growth sector.

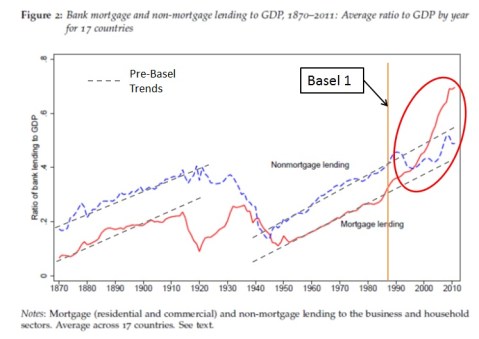

This is in line with what I would expect given that Basel’s capital requirements favour real estate lending over other types. Remember this chart from Jorda et al, which I modified:

Coincidence? Highly unlikely I believe. Although it still isn’t fully clear why manufacturing suffers more than other non-real estate sectors, and this deserves further investigation.

Moreover, they find that once a crisis hits, this misallocation of capital and labour leads to a painfully slow recovery as post-crisis productivity growth is reduced.

They reached a few, but highly important, conclusions, which I have already mentioned on this blog a number of times.

First, they believe that the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis should be seen under a different light:

Our findings suggest a different mechanism, in which the slow recovery after the Great Financial Crisis is the result of a major financial boom and bust, which has left long-lasting scars on the economic tissue (eg BIS (2014), Rogoff (2015)). More specifically, they suggest that what some see as a comparatively disappointing US growth performance in the pre-crisis years, despite a strong financial boom, was actually disappointing, in part, precisely because of the boom. And so has been the post-crisis weak productivity growth.

They also warn about the effects of monetary policy in such a world, which could amplify the misallocation:

Nor is it surprising if monetary policy may not be particularly effective in addressing financial busts. This is not just because its force is dampened by debt overhangs and a broken banking system – the usual “pushing-on-a-string” argument. It may also be because loose monetary policy is a blunt tool to correct the resource misallocations that developed during the previous expansion, as it was a factor contributing to them in the first place.

While a number of economists would argue that current monetary policy isn’t loose, the argument still stands. Loose or not, the allocation of credit still occurs through Basel’s lens. And Borio ends this paper by highlighting that there may be a mechanism that distorts credit allocation that he hasn’t yet uncovered. Well, perhaps banking regulation would be a good starting point for further research. Unfortunately, Borio works for the BIS, which devised our whole bank regulatory framework…

It’s an interesting paper. I have something I’ve been sitting on for a while about labor reallocation during the business cycle in the US, where we have detailed statistics on not only sectors like manufacturing, but different kinds of manufacturing, for example. The upshot is that in an average business cycle the size of the bust, and the boom in employment in a sector, relative to its size/trend, is directly correlated with distance from final consumption ie more or less exactly what you’d expect if, as Austrians argue, the business cycle is closely tied to the role of interest rates in coordinating the appropriate degree of “roundaboutness” to production.

Andrew, are you talking about a published paper? If yes, do you have a link/name? Thanks

Not published, my sense is that the analysis I did would not be regarded as sufficiently “novel” or sophisticated plus I’m not really sure how much luck I could expect to have submitting a paper to a journal as both an uncredentialed unknown and without an academic affiliation. If you’re interested in it I can send you a spreadsheet of the data I looked at with some explanatory notes. Maybe if you think it’s worth publishing it actually might be!