Crush RWAs to end secular stagnation?

Some BIS researchers very recently published this piece of research demonstrating that the growth of the financial sector was linked to lower productivity in the economy. MCK in FT Alphaville commented on it and reached the wrong conclusion (the title of his post is ‘Crush the financial sector, end the great stagnation?’, though he could be forgiven given that the BIS paper itself is titled ‘Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?’).

I have attempted in previous posts to explain why Basel risk-weighted assets (RWAs) were the root cause of the misallocation of bank credit and hence the misallocation of capital in the economy prior to the financial crisis: in order to optimise return on equity, bankers were incentivised by RWAs to allocate a growing share of available loanable funds to the real estate sector, creating an unsustainable boom. I also speculated that, consequently, fewer financial resources were hence available for sectors that were penalised by regulatory-defined high RWAs (i.e. business lending), and that this could be one of the main causes of the so-called ‘secular stagnation’.

I have also regularly criticized governments’ and central banks’ schemes such as FLS and TLTRO when they were announced, as they could simply not address the fundamental problem that Basel had introduced a few decades earlier.

I have recently pointed out that new studies seem to highlight that, indeed, real estate lending had overtaken business lending for the first time in the past 150 years exactly after Basel 1 was put in place at the end of the 1980s, and that the growth of business lending had been lower since then. (Same chart again. Yes it is that important)

This new BIS study is remarkably linked, although its authors don’t seem to have noticed. This is what they conclude:

In our model, we first show how an exogenous increase in financial sector growth can reduce total factor productivity growth. This is a consequence of the fact that financial sector growth benefits disproportionately high collateral/low productivity projects. This mechanism reflects the fact that periods of high financial sector growth often coincide with the strong development in sectors like construction, where returns on projects are relatively easy to pledge as collateral but productivity (growth) is relatively low. […]

First, at the aggregate level, financial sector growth is negatively correlated with total factor productivity growth. Second, this negative correlation arises both because financial sector growth disproportionately benefits to low productivity/high collateral sectors and because there is an externality that creates a possible misallocation of skilled labour.

Replace some of the terms above with RWAs and you get the right picture. What those researchers miss is that the growth of the financial sector has been similar in previous periods over the past 150 years, with no decline in secular growth rate and productivity. However, what changed since the 1980s is the allocation of this growth. And the dataset this BIS piece examines only starts…in 1980. Their conclusion that high collateral industries would attract a higher share of lending is also coherent with my views, as higher lending collateralisation reduces the required capital buffer than banks need to maintain.

MCK is right when he declares that

the growth of the financial sector has been concentrated in mortgage lending, which means that more lending usually just leads to more building. That’s a problem for aggregate productivity, since the construction industry is one of the few that has consistently gotten less productive over time. For example, Spain had no productivity growth between 1998 and 2007, a period when 20 per cent of all the net job growth can be attributed to the building sector.

But his conclusion that regulation needs to force the banking industry to get smaller is off the mark. Getting rid of the incentives created by RWAs, and the resulting unproductive misallocations, is what is needed.

McKinsey on banking and debt

A recent report by the consultancy McKinsey highlights how much the world has not deleveraged since the onset of the financial crisis. Many newspapers have jumped on the occasion to question whether or not the policies adopted since the crisis were the right ones (FT, Telegraph, The Economist…). This is how the total stock of debt has evolved since 2000:

As the following chart shows, the vast majority of countries saw their overall level of debt increase:

As the following chart shows, the vast majority of countries saw their overall level of debt increase:

McKinsey affirms that “household debt continues to grow rapidly, and deleveraging is rare”, and that the same broadly applies to corporate debt. China is an extreme case: total debt level, as a share of GDP, grew from 121% of GDP in 2000, to 158% in 2007 to…282% at end-H114. And growing.

McKinsey affirms that “household debt continues to grow rapidly, and deleveraging is rare”, and that the same broadly applies to corporate debt. China is an extreme case: total debt level, as a share of GDP, grew from 121% of GDP in 2000, to 158% in 2007 to…282% at end-H114. And growing.

Unsurprisingly, household debt is driven by mortgage lending (including in China). It isn’t a surprise to see house prices increasing in so many countries. How this is a reflection that we currently are in a sustainable recovery, I can’t tell you. How this is a signal that monetary policy has been ‘tight’, I can’t tell you either. If monetary policy has indeed been ‘tight’, then it shows the power of Basel regulation in transforming a ‘tight’ monetary policy into an ‘easy’ one for households through mortgage lending. How this total stock of debt will react when interest rates start rising is anyone’s guess…

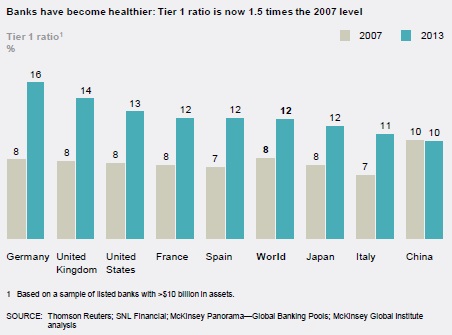

McKinsey’s claim that “banks have become healthier” is questionable at best, as they use regulatory Tier 1 ratios as a benchmark. Indeed a lot of banks have boosted their Tier 1 ratio by reducing RWA density (i.e. the average risk-weight applied to their assets) rather than actually raising or internally generating extra capital.

As expected given how capital intensive corporate lending has become thanks to our banking regulatory framework, and in line with recent research, banks are now mostly funding households at the expense of businesses:

As expected given how capital intensive corporate lending has become thanks to our banking regulatory framework, and in line with recent research, banks are now mostly funding households at the expense of businesses:

McKinsey highlights that P2P lending, while still small in terms of total volume, doubles in size every year, and is mostly present in China and the US.

And in fact, in another article, McKinsey explains that the digital revolution is going to severely hit retail banking. I have several times described that banks’ IT systems were on average out-of-date, that this weighed on their cost efficiency and hence profitability, and that it even possibly impaired the monetary policy transmission channel. I also said that banks needed to react urgently if they were not to be taken over by more recent, more efficient, IT-enabled competitors. A point also made in The End of Banking, according to which technology allows us to get rid of banks altogether.

McKinsey is now backing up those claims with interesting estimates. According to the consultancy, and unsurprisingly, operating costs would be the main beneficiary of a more modern IT framework:

McKinsey goes as far as declaring that:

McKinsey goes as far as declaring that:

The urgency of acting is acute. Banks have three to five years at most to become digitally proficient. If they fail to take action, they risk entering a spiral of decline similar to laggards in other industries.

Unfortunately, current extra regulatory costs and litigation charges are making it very hard for banks to allocate any budget to replace antiquated IT systems.

If banks already had those systems in place as of today, I would expect to see lending rates declining further – in line with monetary policy – across all lending products as margin compression becomes less of an issue. In a world where banks have zero operating cost, its net interest income doesn’t need to be high to generate a net profit.

In the end, regulators are shooting themselves in the foot: not only new regulations and continuous litigations may well have the effect of facilitating new non-banking firms’ takeover of the financial system, but also monetary policy cannot have the effect that regulators/central bankers themselves desire.

Cachanosky on the productivity norm, Hayek’s rule and NGDP targeting

Nicolas Cachanosky and I should get married (intellectually, don’t get overexcited). Some time ago, I wrote about his very interesting paper attempting to start the integration of finance and Austrian capital theories. A couple of weeks ago, I discovered another of his papers, published a year ago, but which I had completely missed (coincidentally, Ben Southwood also discovered that paper at the exact same time).

Titled Hayek’s Rule, NGDP Targeting, and the Productivity Norm: Theory and Application, this paper is an excellent summary of the policies named above and the theories underpinning them. It includes both theoretical and practical challenges to some of those theories. Cachanosky’s paper reflects pretty much exactly my views and deserved to be quoted at length.

Cachanosky defines the productivity norm as “the idea that the price level should be allowed to adjust inversely to changes in productivity. […] In other words, money supply should react to changes in money demand, not to changes in production efficiency.” Referring to the equation of exchange, he adds that “because a change in productivity is not in itself a sign of monetary disequilibrium, an increase in money supply to offset a fall in P moves the money market outside equilibrium and puts into motion an unnecessary and costly process of readjustment”, which is what current central bank policies of price level targeting do. The productivity norm allows mild secular deflation by not reacting to positive ‘real’ shocks.

He goes on to illustrate in what ways Hayek’s rule and NGDP targeting resemble and differ from the productivity norm:

There are instances where the productivity norm illuminated economists that talked about monetary policy. Two important instances are Hayek during his debate with Keynes on the Great Depression and the market monetarists in the context of the Great Recession. Both, Hayek and market monetarism are concerned with a policy that would keep monetary equilibrium and therefore macroeconomic stability. Hayek’s Rule and NGDP Targeting are the denominations that describe Hayek’s and market monetarism position respectively. Taking the presence of a central bank as a given, Hayek argues that a neutral monetary policy is one that keeps constant nominal income (MV) stable. Sumner argues instead that

“NGDP level targeting (along 5 percent trend growth rate) in the United States prior to 2008 would similarly have helped reduce the severity of the Great Recession.”

Hayek’s Rule of constant nominal income can be understood in total values or as per factor of production. In the former, Hayek’s Rule is a notable case of the productivity norm in which the quantity of factors of production is assumed to be constant. In the latter case, Hayek’s rule becomes the productivity norm. However, for NGDP Targeting to be interpreted as an application that does not deviate from the productivity norm, it should be understood as a target of total NGDP, with an assumption of a 5% increase in the factors of production. In terms of per factor of production, however, NGDP Targeting implies a deviation of 5% from equilibrium in the money market.

Cachanosky then highlights his main criticisms of NGDP targeting as a form of nominal income control, that is the distinction between NGDP as an ‘emergent order’ and NGDP as a ‘designed outcome’. He says that targeting NGDP itself rather than considering NGDP as an outcome of the market can affect the allocation of resources within the NGDP: “the injection point of an increase in money supply defines, at least in the short-run, the effects on relative prices and, as such, the inefficient reallocation of factors of production.” In short, he is referring to the so-called Cantillon effect, in which Scott Sumner does not believe. I am still wondering whether or not this effect could be sterilized (in a closed economy) simply by growing the money supply through injections of equal sums of money directly into everyone’s bank accounts.

To Cachanosky (and Salter), “NGDP level matters, but its composition matters as well.” He believes that targeting an NGDP growth level by itself confuses causes and effects: “that a sound and healthy economy yields a stable NGDP does not mean that to produce a stable NGDP necessary yields a sound and healthy economy.” He points out that the housing bubble is a signal of capital misallocation despite the fact that NGDP growth was pretty stable in pre-crisis years.

I evidently fully agree with him, and my own RWA-based ABCT also points to lending misallocation that would also occur and trigger a crisis despite aggregate lending growth remaining stable or ‘on track’ (whatever that means). I should also add that it is unclear what level of NGDP growth the central bank should target. See the following chart. I can identify many different NGDP growth ‘trends’ since the 1940s, including at least two during the ‘great moderation’. Fluctuations in the trend rate of US NGDP growth can reach several percentage points. What happens if the ‘natural’ NGDP growth changes in the matter of months whereas the central bank continues to target the previous ‘natural’ growth rate? Market monetarists could argue that the differential would remain small, leading to only minor distortions. Possibly, but I am not fully convinced. I also have other objections to NGDP level targeting (related to banking and transmission mechanism), but this post isn’t the right one to elaborate on this (don’t forget that I view NGDP targeting as a better monetary policy than inflation targeting but a ‘less ideal’ alternative to free banking or the productivity norm).

Cachanosky also points out that NGDP targeting policies using total output (Py in the equation of exchange) and total transactions (PT) do not lead to the same result. According to him “the housing bubble before 2008 crisis is an exemplary symptom os this problem, where PT increases faster than Py.”

Cachanosky also points out that NGDP targeting policies using total output (Py in the equation of exchange) and total transactions (PT) do not lead to the same result. According to him “the housing bubble before 2008 crisis is an exemplary symptom os this problem, where PT increases faster than Py.”

Finally, he reminds us that a 100%-reserve banking system would suffer from an inelastic money supply that could not adequately accommodate changes in the demand for money, leading to monetary equilibrium issues.

I can’t reproduce the whole paper here, but it is full of very interesting (though quite technical) details and I strongly encourage you to take a look.

Martin Wolf’s not so shocking shocks

Martin Wolf, FT’s chief economist, recently published a new book, The Shifts and the Shocks. The book reads like a massive Financial Times article. The style is quite ‘heavy’ and not always easy to read: Wolf throws at us numbers and numbers within sentences rather than displaying them in tables. This format is more adapted to newspaper articles.

Overall, it’s typical Martin Wolf, and FT readers surely already know most of the content of the book. I won’t come back to his economic policy advices here, as I wish to focus on a topic more adapted to my blog: his views on banking.

And unfortunately his arguments in this area are rather poor. And poorly researched.

Wolf is a fervent admirer of Hyman Minsky. As a result, he believes that the financial system is inherently unstable and that financial imbalances are endogenously generated. In Minsky’s opinion, crises happen. It’s just the way it is. There is no underlying factor/trigger. This belief is both cynical and wrong, as proved by the stability of both the numerous periods of free banking throughout history (see the track record here) and of the least regulated modern banking systems (which don’t even have lenders of last resort or deposit insurance). But it doesn’t fit Wolf’s story so let’s just forget about it: banking systems are unstable; it’s just the way it is.

Wolf identifies several points that led to the 2000s banking failure. In particular, liberalisation stands out (as you would have guessed) as the main culprit. According to him “by the 1980s and 1990s, a veritable bonfire of regulations was under way, along with a general culture of laissez-faire.” What’s interesting is that Wolf never ever bothers actually providing any evidence of his claims throughout the book (which is surprising given the number of figures included in the 350+ pages). What/how many regulations were scrapped and where? He merely repeats the convenient myth that the banking system was liberalised since the 1980s. We know this is wrong as, while high profile and almost useless rules like Glass-Steagall or the prohibition of interest payment on demand deposits were repealed in the US, the whole banking sector has been re-regulated since Basel 1 by numerous much more subtle and insidious rules, which now govern most banking activities. On a net basis, banking has been more regulated since the 1980s. But it doesn’t fit Wolf’s story so let’s just forget about it: banking systems were liberalised; it’s just the way it is.

Financial innovation was also to blame. Nevermind that those innovations, among them shadow banking, mostly arose from or grew because of Basel incentives. Basel rules provided lower risk-weight on securitized products, helping banks improve their return on regulatory capital. But it doesn’t fit Wolf’s story so let’s just forget about it: greedy bankers always come up with innovations; it’s just the way it is.

The worst is: Wolf does come close to understanding the issue. He rightly blames Basel risk-weights for underweighting sovereign debt. He also rightly blames banks’ risk management models (which are based on Basel guidance and validated by regulators). Still, he never makes the link between real estate booms throughout the world and low RE lending/RE securitized risk-weights (and US housing agencies)*. Housing booms happened as a consequence of inequality and savings gluts; it’s just the way it is.

All this leads Wolf to attack the new classical assumptions of efficient (and self-correcting) markets and rational expectations. While he may have a point, the reasoning that led to this conclusion couldn’t be further from the truth: markets have never been free in the pre-crisis era. Rational expectations indeed deserve to be questioned, but in no way does this cast doubt on the free market dynamic price-researching process. He also rightly criticises inflation targeting, but his remedy, higher inflation targets and government deficits financed through money printing, entirely miss the point.

What are Wolf other solutions? He first discusses alternative economic theoretical frameworks. He discusses the view of Austrians and agrees with them about banking but dismisses them outright as ‘liquidationists’ (the usual straw man argument being something like ‘look what happened when Hoover’s Treasury Secretary Mellon recommended liquidations during the Depression: a catastrophe’; sorry Martin, but Hoover never implemented Mellon’s measures…). He also only relies on a certain Rothbardian view of the Austrian tradition and quotes Jesus Huerta de Soto. It would have been interesting to discuss other Austrian schools of thought and writers, such as Selgin, White and Horwitz, who have an entirely different perception of what to do during a crisis. But he probably has never heard of them. He once again completely misunderstands Austrian arguments when he wonders how business people could so easily be misled by wrong monetary policy (and he, incredibly, believes this questions the very Austrian belief in laissez-faire), and when he cannot see that Austrians’ goals is to prevent the boom phase of the cycle, not ‘liquidate’ once the bust strikes…

Unsurprisingly, post-Keynesian Minsky is his school of choice. But he also partly endorses Modern Monetary Theory, and in particular its banking view:

banks do not lend out their reserves at the central bank. Banks create loans on their own, as already explained above. They do not need reserves to do so and, indeed, in most periods, their holdings of reserves are negligible.

I have already written at length why this view (the ‘endogenous money’ theory) is inaccurate (see here, here, here, here and here).

He then takes on finance and banking reform. He doubts of the effectiveness of Basel 3 (which he judges ‘astonishingly complex’) and macro-prudential measures, and I won’t disagree with him. But what he proposes is unclear. He seems to endorse a form of 100% reserve banking (the so-called Chicago Plan). As I have written on this blog before, I am really unsure that such form of banking, which cannot respond to fluctuations in the demand for money and potentially create monetary disequilibrium, would work well. Alternatively, he suggests almost getting rid of risk-weighted assets and hybrid capital instruments (he doesn’t understand their use… shareholder dilution anyone?) and force banks to build thicker equity buffers and report a simple leverage ratio. He dismisses the fact that higher capital requirements would impact economic activity by saying:

Nobody knows whether higher equity would mean a (or even any) significant loss of economic opportunities, though lobbyists for banks suggest that much higher equity ratios would mean the end of our economy. This is widely exaggerated. After all, banks are for the most part not funding new business activities, but rather the purchase of existing assets. The economic value of that is open to question.

Apart from the fact that he exaggerates banking lobbyists’ claims to in turn accuse them of… exaggerating, he here again demonstrates his ignorance of banking history. Before Basel rules, banks’ lending flows were mostly oriented towards productive commercial activities (strikingly, real estate lending only represented 3 to 8% of US banks’ balance sheets before the Great Depression). ‘Unproductive’ real estate lending only took over after the Basel ruleset was passed.

The case for higher capital requirements is not very convincing and primarily depends on the way rules are enforced. Moreover, there is too much focus on ‘equity’. Wolf got part of his inspiration from Admati and Hellwig’s book, The Bankers’ New Clothes. But after a rather awkward exchange I had with Admati on Twitter, I question their actual understanding of bank accounting:

While his discussion of the Eurozone problems is quite interesting, his description of the Eurozone crisis still partly rests on false assumptions about the banking system. Unfortunately, it is sad to see that an experienced economist such as Martin Wolf can write a whole book attacking a straw man.

* In a rather comical moment, Wolf finds ‘unconvincing’ that US government housing policy could seriously inflate a housing bubble. To justify his opinion, he quotes three US Republican politicians who said that this view “largely ignores the credit bubble beyond housing. Credit spreads declined not just for housing, but also for other asset classes like commercial real estate.” Let’s just not tell them that ‘Real Estate’ comprises both residential housing and CRE…

The mystery of collateral

Collateral has been the new fashionable area of finance and capital markets research over the past few years. Collateral and its associated transactions have been blamed for all the ills of the crisis, from runs on banks’ short-term wholesale funding to a scarcity of safe assets preventing an appropriate recovery. Some financial journalists have jumped on the bandwagon: everything is now seen through a ‘collateral lens’. The words ‘assets’, and, to a lesser extent ‘liquidity’ and ‘money’ themselves, have lost their meaning: all are now being replaced by ‘collateral’, or used interchangeably, by people who don’t seem to understand the differences.

A few researchers are the root cause. The work of Singh keeps referring to any sort of asset transfer between two parties as ‘collateral transfer’. This is wrong. Assets are assets. Securities are securities, a subset of assets. Collateral can be any type of assets, if designated and pledged as such to secure a lending or derivative transaction. Real estate, commodities and Treasuries can all be used as collateral. Money too. Unlike what Singh and his followers claim, a securities lender lends a security not a collateral. Whether or not this security is used as collateral in further transactions is an independent event.

This unfortunate vocabulary problem has led to perverse ramifications: all liquid assets, or, as they often say, collateral, are now seen as new forms of money (see chart below, from this paper). Specifically, collateral becomes “the money of the shadow banking system”. I believe this is incorrect. Collateral is used by shadow banks to get hold of money proper. Building on this line of reasoning, people like Pozsar assert that repo transactions are money… This makes even less sense. Repos simply are collateralised lending transactions. Nobody exchanges repos. The assets swapped through a repo (money and securities) could however be exchanged further. Depressingly, this view is taken increasingly seriously. As this recent post by Frances Coppola demonstrates, all assets seem now to be considered as money. This view is wrong in many ways, but I am ready to reconsider my position if ever Treasuries or RMBSs start being accepted as media of exchange at Walmart, or between Aston Martin and its suppliers. Others have completely misunderstood the differences between loan collateralisation and loan funding, which is at the heart of the issue: you don’t fund a loan, whether in the light or the dark side of the banking system, with collateral! The monetary base/high-powered money/cash/currency, is the only medium of settlement, the only asset that qualifies as a generally-accepted medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account (the traditional definition of money).

There is one exception though. Some particular transactions involve, not a non-money asset for money swap, but non-money asset for another non-money asset swap. This is almost a barter-like transaction, which does occur from time to time in securities lending activities (the lender lends a security for a given maturity, and the borrower pledges another security as collateral). Nonetheless, the accounting (including haircuts and interest calculations) in such circumstances is still being made through the use of market prices defined in terms of the monetary base.

Still, collateral seems to have some mysterious properties and Singh’s work offers some interesting insights into this peculiar world. The evolution of the collateral market might well have very deep effects on the economy. The facilitation of collateral use and rehypothecation, as well as the requirements to use them, either through specific regulatory and contractual frameworks, through the spread of new technology, new accounting rules or simply through the increased abundance of ‘safe assets’ (i.e. increased sovereign debt issuance), might well play a role in business cycles, via the interest rate channel. Indeed, by facilitating or requiring the use of increasingly abundant collateral, interest rates tend to fall. The concept of collateral velocity is in itself valuable: when velocity increases, interest rates tend to fall further as more transactions are executed on a secured basis. Still, are those transactions, and the resulting fall in interest rates, legitimate from an economic point of view? What are the possible effects on the generation of malinvestments?

An example: let’s imagine that a legal framework clarification or modification, and/or regulatory change, increases the use and velocity of safe collateral (government debt). New technological improvements also facilitate the accounting, transfer, and controlling processes of collateral. This increases the demand for government debt, which depresses its yield. Motivated by lower yield, the government indeed issues more debt that flow through financial markets. As the newly-enabled average velocity of collateral increases substantially, more leveraged secured transactions take place and at lower interest rates. While banks still have exogenous limits to credit expansion (as the monetary base is controlled by the central bank), the price of credit (i.e. endogenous money creation) has therefore decreased as a result of a mere regulatory/legal/technological change.

I have been wondering for a while whether or not such a change in the regulatory paradigm of collateral use could actually trigger an Austrian-type business cycle. I do not yet have an answer. Implications seem to be both economic and philosophical. What are the limits to property rights transfer? How would a fully laisse-faire market deal with collateral and react to such technological changes? Perhaps collateral has no real influence on business fluctuations after all. There is nevertheless merit in investigating further. I am likely to explore the collateral topic over the next few months.

PS: I will be travelling in North America over the next 10 days, so might not update this blog much.

* There are many many flaws in Frances’ piece. See this one:

But suppose that instead of a sterling bank account, a smartcard or a smartphone app enabled me to pay a bill in Euros directly from my holdings of UK gilts? This is not as unlikely as it sounds. It would actually be two transactions – a sale of gilts for sterling and a GBPEUR exchange. This pair of transactions in today’s liquid markets could be done instantaneously. I would in effect have paid for my meal with UK government debt.

She fails to see that she would have paid for her mean with Sterling, not with government debt! Government debt must be converted into currency as it is not a medium of exchange/settlement.

Financial instability: Beckworth and output gap

I recently mentioned David Beckworth’s excellent new paper on inflation targeting, which, according to him, promotes financial instability by inadequately responding to supply shocks. Like free bankers and some other economists, Beckworth understands the effects of productivity growth on prices and the distorting economic effects of inflation targeting in a period of productivity improvements.

Nevertheless, I am a left a little surprised by a few of his claims (on his blog), some of which seem to be in contradiction with his paper: according to him, current US output gap demonstrates that the nominal natural rate of interest has been negative for a while. Consequently, the current Fed rate isn’t too low and raising it would be premature.

While I believe that the real natural interest rate (in terms of money) is very unlikely to ever be negative (though some dispute this), it is theoretically and empirically unclear whether or not the nominal natural rate could fall in negative territory, especially for such a long time.

Beckworth uses a measure of US output gap calculated by the CBO and derived from their potential GDP estimate. This is where I become very sceptical. GDP itself is already subject to calculation errors and multiple revisions. Furthermore, there are so many variables and methodologies involved in calculating ‘potential’ GDP, that any output gap estimate takes the risk of being meaningless due to extreme inaccuracy, if not completely flawed or misleading.

This is the US potential GDP, as estimated by the CBO:

Wait a minute. For most of the economic bubble of the 2000s, the US was below potential? This estimate seems to believe that credit-fuelled pre-crisis years were merely in line with ‘potential’. This is hardly believable, and this reminds me of the justification used by many Keynesian economists: we should have used more fiscal stimulus as we are below ‘trend’ (‘trend’ being calculated from 2007 of course, as if the bubble years had never happened). Does this also mean that the natural rate of interest has been negative or close to zero since 2001? This seems to contradict Beckworth’s own inflation targeting article, in which he says that the Fed rate was likely too low during the period.

Let’s have a look at a few examples of the wide range of potential GDP estimates (and hence output gap) that are available out there*. The Economic Report of the President estimates potential GDP as even higher than the CBO’s (source: Morgan Stanley):

The Fed of San Francisco, on the other hand, estimated very different output gap variations. According to some measures, the US is currently… above potential:

Some of the methodologies used to calculate some of those estimates might well be inaccurate, or simply wrong. Still, this clearly shows how hard it is to determine potential GDP and thus the output gap. Any conclusion or recommendation based on such dataset seems to me to reflect conjectures more than evidences.

This is where we get to my point.

In his very good article, Beckworth brilliantly declares that:

the productivity gains will also create deflationary pressures that an inflation-targeting central bank will try to offset. To do that, the central bank will have to lower its target interest rate even though the natural interest rate is going up. Monetary authorities, therefore, will be pushing short-term interest rates below the stable, market-clearing level. To the extent this interest rate gap is expected to persist, long-term interest rates will also be pushed below their natural rate level. These developments mean firms will see an inordinately low cost of capital, investors will see great arbitrage opportunities, and households will be incentivized to take on more debt. This opens the door for unwarranted capital accumulation, excessive reaching for yield, too much leverage, soaring asset prices, and ultimately a buildup of financial imbalances. By trying to promote price stability, then, the central bank will be fostering financial instability.

Please see the bold part (my emphasis): isn’t it what we are currently experiencing? It looks to me that the current state of financial markets exactly reflects Beckworth’s description of a situation in which the central bank rate is below the natural rate. This is also what the BIS warned against, explicitely rejected by Beckworth on the basis of this CBO output gap estimate. (see also this recent FT report on bubbles forming in credit markets)

I am asking here how much trust we should place in some potentially very inaccurate estimates.

Perhaps the risk-aversion suppression and search for yield of the system is not apparent to everyone, including Beckworth, not helping him diagnose our current excesses. But, his ‘indicators that don’t show asset price froth’ are arguable: the risk premium between Baa-rated yields and Treasuries are ‘elevated’ due to QE pushing yields on Treasuries lower, and it doesn’t mean much that households still hold more liquid assets than in the financial boom years of 1990-2007.

At the end of the day, we should perhaps start relying on actual** – rather than estimated and potentially flawed – indicators for policy-making purposes (that is, as long as discretion is in place). Had US GDP been considered as above potential in the pre-crisis years and the Fed stance adapted as a result, the impact of the financial crisis might have been far less devastating. I agree with Beckworth: time to end inflation targeting.

* The IMF estimate also shows that the US was merely in line with potential as of 2007. Others are more ‘realistic’ but as the charts below demonstrate, estimates vary widely, along with confidence intervals (link, as well as this full report for tons of other output gap charts from the same authors):

** I understand and agree that ‘actual’ market and economic data can also be subject to interpretation. I believe, however, that the range of interpretations is narrower: these datasets represents more ‘crude’ or ‘hard’ data that haven’t been digested through multiple, potentially biased, statistical computations.

Sovereign debt crisis: another Basel creature?

I often refer to the distortive effects of RWA on the housing and business/SME lending channels. What I don’t say that often is that Basel’s regulations have also other distortive effects, perhaps slightly less obvious at first sight.

Basel is highly likely to be partially responsible for sovereign states’ over-indebtedness, by artificially maintaining interest rates paid by governments below their ‘natural’ level.

How? Through one particular mechanism historically, that you probably start knowing quite well: risk-weighted assets (RWA). Basel 1 indeed applied a 0% risk-weight on OECD countries’ sovereign debt*, meaning banks could load up their balance sheet with such instruments without negatively impacting their regulatory capital ratios at all. Interest income earned on sovereign debt was thus almost ‘free’: banks were incentivised to accumulate them to maximise capital-efficiency and RoE.

This extra demand is likely to have had the effect of pushing interest rates down for a number of countries, whose governments found it therefore much easier to fund their electoral promises. In the end, the financial and economic crisis was triggered by the over-issuance of very specific types of debt: housing/mortgage, sovereign and some structured products. All those asset classes had one thing in common: a preferential capital treatment under Basel’s banking regulations.

Basel 2 introduced some granularity but fundamentally didn’t change anything. Basel 3 doesn’t really help either, although local and Basel regulators have recently announced possible alterations to this latest set of rules in order to force banks to apply risk-weights to sovereign bonds (one option is to introduce a floor). Some banks have already implemented such changes (which cost billions in extra capital requirements).

While those measures go in the right direction, Basel 3 has also introduced a regulatory tool that goes precisely the opposite way: the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). The LCR requires banks to maintain a large enough liquidity buffer (made of highly-liquid and high quality assets) to cover a 30-day cash outflow. As you may have already guessed, eligible assets include mostly… government securities**.

Here again, Basel artificially elevates the demand for sovereign debt in order to comply with regulatory requirements, pushing yields down in the process. This has two consequences: 1. governments could find a lot easier to raise cash than in free market conditions (with all the perverse incentives this has on a democratic process unconstrained by economic reality) and 2. as sovereign yields are used as risk-free rate benchmarks in the valuation of all other asset classes, the fall in yield due to the artificially-increased demand could well play the role of a mini-QE, boosting asset prices across the board ceteris paribus.

We end up with a policy mix that contaminates both central banks’ monetary policies and domestic political debates. But, worst of all, it is a real malinvestment engine, which trades short-term financial solidity for long-term instability.

* Some non-OECD regions of the world also allow their domestic banks to use 0% risk-weight on domestic sovereign debt. For instance, many African countries are allowed to apply 0% weighing on the sovereign debt of their local governments despite the obvious credit risk it represents as well as its poor marketability (this is partly mitigated as this debt is often repoable at the regional central bank). Moreover, the same regulators prevent their domestic banks from investing their liquidity in Treasuries or European debt, with the obvious goal of benefiting those African states. Consequently, illiquid and risky sovereign bonds comprise most of those banks’ “liquidity” buffers, evidently not making those banking systems much safer…

** The LCR is partly responsible for the ‘shortage of safe assets’ story.

Lars Christensen on Yellen and bubbles, and UK regulators at full speed

Lars Christensen published a sarcastic post on his blog, which coincidentally treats the monetary policy and bubbles problem as the same time as my previous post. I fully agree with him that Yellen’s comments are ridiculous.

This is Lars:

it seems to part of a growing tendency among central bankers globally to be obsessing about “financial stability” and “bubbles”, while at the same time increasingly pushing their primary nominal targets in the background.

While I agree with Lars that central banks should provide ‘nominal stability’, I don’t think inflation targeting provides such framework (and I believe Lars agrees). Inflation is very hard to measure, let alone to define, and can be very misleading (Scott Sumner believes that inflation indicators are meaningless). According to a Wicksellian framework, it does look like something’s wrong with interest rates at the moment. Banking regulation, due to its roles in ‘channelling’ interest rates, surely also plays a big role that monetary policy cannot influence. In the end, maintaining inflation right on target is in no way insurance of actual nominal (and financial) stability.

David Beckworth, in a new paper published a few days ago, also criticised inflation targeting on the ground that it contributes to financial instability. I agree with Market Monetarists that a policy stabilising NGDP growth would provide a more robust economy and financial system, though it is in my view still imperfect (I’ll come back to that in another post).

Totally unrelated: in the UK, regulators are working at full speed. Here is a summary of some of the latest regulatory announcements:

- Regulators believe that asset managers ‘waste’ too much client money on sell-side analysts research and want to regulate the process, risking to transform the market into an oligopoly as smaller research providers may not be able to cope with the reduced fee-generation (see here and here)

- HMRC wants to get the power to access your bank account and check your spending habits without going through court to make sure that you are able to pay the taxes they claim you owe them (even if they are wrong). I have personally dealt many times with HMRC (I didn’t owe them money, they did) and the least I can say is that it wasn’t necessarily a pleasant experience: waiting 45min on the phone to end up speaking to someone who sounds very suspicious that you are trying to trick tax authorities… (to be fair, I also ended up speaking to competent and pleasant people) HMRC makes mistakes all the time and I would be very cautious in granting them such powers… (see here and here)

- New rules capping the fees payday lenders can charge are effectively about to kill a large number of them… It probably won’t help much (see here)

- Bank account holders aren’t taking advantage of the best offers available to them and don’t spend their time constantly changing bank to get the best pricing and as a result earn poor returns? The regulator also wants to change that, though I submit that it should tell his boss (the BoE) that, if savers indeed earn poor returns, it possibly is because rates aren’t very high… (see here)

- The BoE and PRA want global banking regulators to reduce RWAs or capital requirements for small banks. Not saying this is a bad thing, but this sounds kind of contradictory to me, given everything we’ve been hearing for years from the same regulators… (see here)

Is the BIS on the Dark Side of macroeconomics?

The BIS has got a hobby: to annoy other economists and central bankers. It’s a good thing. It published its annual report about two weeks ago, and the least we can say is that it didn’t please many.

Gavin Davies wrote a very good piece in the FT last week, summarising current opposite views: “Keynesian Yellen versus Wicksellian BIS”. What’s interesting is that Davies views the BIS as representing the ‘Wicksellian’ view of interest rates: that current interest rates are lower than their natural level (i.e. monetary policy is ‘loose’ or ‘easy’). On the other hand, Scott Sumner and Ryan Avent seem to precisely believe the opposite: that current rates are higher than their natural level and that the BIS is mistaken in believing that low nominal rates mean easy money. This is hard to reconcile both views.

Neither is the BIS particularly explicit. Why does it believe that interest rates are low? Because their headline nominal level is low? Because their real level is low? Or because its own natural rates estimates show that central banks’ rates are low?

It is hard to estimate the Wicksellian ‘natural rate’ of interest. Some people, such as Thomas Aubrey, attempt to estimate the natural rate using the marginal product of capital theory. There are many theories of the rate of interest. Fisher (described by Milton Friedman as America’s best ever economist), Bohm-Bawerk, and Mises would argue that the natural interest rate is defined by time preference (even though they differ on details), and Keynes liquidity preference. Some economists, such as Miles Kimball, currently argue that the natural rate of interest is negative. This view is hard to reconcile with any of the theories listed above. Fisher himself declared in The Rate of Interest that interest rates in money terms cannot be negative (they can in commodity terms).

Unfortunately, and as I have been witnessing for a while now, Wicksell is very often misinterpreted, even by senior economists. The latest example is Paul Krugman, evidently not a BIS fan. Apart from his misinterpretation of Wicksell (see below), he shot himself in the foot by declaring (my emphasis):

Now, what about the BIS? It is arguing that central banks have consistently kept rates too low for the past couple of decades. But this is not a statement about the Wicksellian natural rate. After all, inflation is lower now than it was 20 years ago.

Given that we indeed got two decades of asset bubbles and crashes, it looks to me that the BIS view was vindicated…

Furthermore, in a very good post, Thomas Aubrey corrects some of those misconceptions:

The second issue to note is that when the natural rate is higher than the money rate there is no necessary impact on the general price level. As the Swedish economist Bertie Ohlin pointed in the 1930s, excess liquidity created during a Wicksellian cumulative process can flow into financial assets instead of the real economy. Hence a Wicksellian cumulative process can have almost no discernible impact on the general price level as was seen during the 1920s in the US, the 1980s in Japan and more recently in the credit bubble between 2002-2007.

(Bob Murphy also wrote a very good post here on Krugman vs. Wicksell)

But there are other problematic issues. First, inflation (as defined by CPI/RPI/general increase in the price level) itself is hard to measure, and can be misleading. Second, as I highlighted in an earlier post, wealthy people, who are the ones who own most investible assets, experience higher inflation rates. In order to protect their wealth from declining through negative real returns (what Keynes called the ‘euthanasia of the rentiers’), they have to invest it in higher-yielding (and higher-risk) assets, causing bubbles is some asset classes (while expectations that central bank support to asset prices will remain and allow them to earn a free lunch, effectively suppressing risk-aversion).

If natural rates were negative – or at least very low – and the environment deflationary, it is unlikely that we would witness such hunt for yield: people care about real rates, not nominal ones (though in the short-run, money illusion can indeed prevail). But this is not only an ultra-rich problem: there are plenty of stories of less well-off savers complaining of reduced purchasing power.

Meanwhile, the rest of the population and overleveraged companies, supposedly helped by lower interest rates, seem not to deleverage much: overall debt levels either stagnate or even increase in most economies, as the BIS pointed out.

Banks also suffer from the combination of low rates* and higher regulatory requirements that continue to pressurise their bottom line, and have ceased to pass lower rates on to their customers.

In this context, the BIS seems to have a point: rates may well be too low. Current interest rate levels seem to only prevent the reallocation of capital towards more economically efficient uses, while struggling banks are not able to channel funds to productive companies.

Critics of the BIS point to their call to rise rates to counter inflation back in 2011. Inflation, as conventionally measured, indeed hasn’t stricken in many countries. In the UK and some other European countries though, complaints about quickly rising prices and falling purchasing power have been more than common (and I’m not even referring to house price inflation). This mismatch between aggregate inflation indicators and widespread perception is a big issue, which underlies financial risk-taking.

In the end, Keynes’ euthanasia of the rentiers only seem to prop up dying overleveraged businesses and promote asset bubbles (and financial instability) as those rentiers pile in the same asset classes. I side with the BIS in believing this is not a good and sustainable policy.

I also side with the BIS and with Mohamed El-Erian in believing in the poor forecasting ability of most central bankers, who seem to constantly display a dovish view of the economy, which apparently experiences never-ending ‘slack’, as well as the very uncertain effect of macro-prudential policies, which cannot and will not get in all the cracks. Nevertheless, many mainstream economists and economic publications seem to be overconfident in the effectiveness of macro-prudential policies (see The Economist here, Yellen here, Haldane here, who calls macropru policies “targeted lightning strikes”…).

While central banks’ rates should probably already have risen in several countries (and remain low in others, hence the absurdity of having a single monetary policy for the whole Eurozone), everybody should keep the BIS warnings in mind: after all, they were already warning us before the financial crisis, yet few people listened and many laughed at them.

Unfortunately, politicians and regulators have repeated some of the mistakes made during the Great Depression: they increased regulation of business and banking while the economy was struggling. I have many times referred to the concept of regulatory uncertainty, as well as the over-regulation that most businesses are now subject to (in the US at least, though this is also valid in most European countries). Businesses complaints have been increasing and The Economist reported on that issue last week.

In the meantime, while monetary policy has done (almost) everything it could to boost credit growth and to prevent the money supply from collapsing, harsher banking regulation has been telling banks to do the exact opposite: raise capital, deleverage, and don’t take too much risk.

In the end, monetary policy cannot fix those micro-level issues. It is time to admit that we do not live in the same microeconomic environment as before the crisis. What about cutting red tape to unleash growth rather than risk another financial crisis?

* Yes, for banks, rates are low, whichever way you look at them. Banks can simply not function by earning zero income on their interest-earning assets (loan book and securities portfolio).

PS: Noah Smith, another member of the anti-BIS crowd, has a nonsense ‘let’s keep interest rate low forever’-type article here: raising interest rates would lead to an asset price crash, so we should keep them low to have a crash later. Thanks Noah. The way he describes a speculative bubble is also wrong (my emphasis):

The theory of speculation tells us that bubbles form when people think they can find some greater fool to sell to. But when practically everyone is convinced that asset prices are relatively high, like now, it’s pretty obvious that there aren’t many greater fools out there.

Really? No, speculation involved buying as long as you believe you can get the right timing to exit the position. Even if everyone believed that asset prices were overvalued, as long as investors expect prices to continue to increase, speculation would continue: profits can still be made by exiting on time, even if you join the party late.

PPS: A particularly interesting chart from the BIS report was the one below:

It is interesting to see how coordinated financial cycles have become. Yet the BIS seems not to be able to figure out that its own work (i.e. Basel banking rules) could well be the common denominator of those cycles (which were rarely that synchronised in the past).

It is interesting to see how coordinated financial cycles have become. Yet the BIS seems not to be able to figure out that its own work (i.e. Basel banking rules) could well be the common denominator of those cycles (which were rarely that synchronised in the past).

A brief comment on Piketty

Thomas Piketty’s new book, Capital in the 21st Century, is both controversial and a great success. Despite its flaws, its success reflects growing concerns that need to be addressed. I finished reading the book a few weeks ago and actually found it quite interesting (apart from its nonsensical last section) and easy to read. I am not going to review it here: there are already possibly 1,000 reviews available online, focusing on the underlying economic theory or on the data-picking of the book.

One thing struck me though: the lack of explanation as to why the data evolves the way it does. Piketty seems to believe that this is the result of a ‘fundamental and inherent’ characteristic of capitalism (‘r > g’). Fair enough, but despite all his expertise in the unequality area, Prof Piketty seems to lack the necessary knowledge in other economic and finance areas to reach the right conclusions.

He uses the three following charts to demonstrate the evolution of wealth as a share of national income throughout the last few centuries.

In France:

Now compare with the following charts:

A lot of people have already pointed out that most of what Piketty sees as ‘rise’ in inequality in fact emanates almost entirely from housing bubbles… This is obvious for Britain and France, though I am surprised by Piketty’s US chart as the US clearly experienced a housing bubble as well, which seems not to be reflected in in his wealth data: US housing roughly represented the same share of wealth in 2010 as in 1990. This may be due to the fact that, in 2010, US housing prices had collapsed, which is not captured by Piketty’s chart (which isn’t smooth enough, i.e. one data point every 20 years).

Piketty admits several times in his book that ‘bubbles’ were partly the underlying cause of those rises. Yet, to him, those bubbles seem to be fundamental features of capitalism and government must intervene by redistributing the increased capital stock. As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I encourage him to dig into Basel banking regulations, which distort lending by benefiting housing and were implemented almost exactly when housing wealth started rising. He would probably notice that a large part of the increase in pre-crisis wealth inequality was due to a combination of banking regulation and interest rates below their ‘natural’ level*, both creatures of government intervention, not of free market capitalism…

* Planning restrictions in places like London and Paris also are to blame, I know, though they can’t explain everything. And, anyway, they also reflect government measures…

Recent Comments