Regulating problems away doesn’t work

By ‘regulating’ the symptoms one does not cure the underlying disease. A few more examples in the press of this phenomenon that I keep describing:

– It’s no news that banks are being pressurised from all sides by regulation and lawsuits. The results? Banks aren’t that profitable anymore and remuneration stalls or even falls. Victory then? Wait a minute. Bloomberg reports that there is increased demand for young bankers by private equity funds, which are unsurprisingly more lightly regulated. This is part of a bigger trend that sees investors, funding and, as a result, credit, fleeing the traditional banking system towards the higher-yielding shadow banking system.

– The Economist also reports the same rebalancing towards shadow banking in China. I have already called China a ‘Spontaneous Finance Frankenstein’ given its strong, unnatural, regulatory-driven financial sector. This is typical:

China’s cap on deposit rates at banks is causing money to flood into shadow-banking products such as those offered by “trust” companies in search of higher yields. Offerings by internet firms, with their large existing customer bases, have opened the spigots wider. […]

Some see these online firms as a serious long-term threat to banks and the government’s ability to control the financial sector, prompting noisy demands (mostly by banks) to regulate the upstarts. Regulators have not yet expressed a clear view, but some observers see signals of a looming regulatory crackdown in attacks by the official media; a financial editor on the state-run television network recently branded online financial firms vampires and parasites.

What would be the effects of regulators successfully regulating those various areas of the shadow financial sector? A ‘shadow shadow’ banking sector would emerge. Liquidity, when in abundance, always finds its way. Regulation drives financial innovations, creating systemic risks through complex shadowy interlinked financial products and entities.

One does not regulate symptoms away. Market actors are the only natural, and the best, regulators.

Inside regulator trading

While some people keep praising the virtues of regulation on anything and everything (see Izabella Kaminska here on Bitcoin), a brand new study seems to picture a slightly less rosy view of regulators…

(This research was originally pointed by Lars Christensen on his blog and Facebook account. Thank you again Lars)

The abstract is telling:

We use a new data set obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request to investigate the trading strategies of the employees of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). We find that a hedge portfolio that goes long on SEC employees’ buys and short on SEC employees’ sells earns positive and economically significant abnormal returns of (i) about 4 % per year for all securities in general; and (ii) about 8.5% in U.S. common stocks in particular. The abnormal returns stem not from the buys but from the sale of stock ahead of a decline in stock prices. We find that at least some of these SEC employee trading profits are information based, as they tend to divest (i) in the run-up to SEC enforcement actions; and (ii) in the interim period between a corporate insider’s paper-based filing of the sale of restricted stock with the SEC and the appearance of the electronic record of such sale online on EDGAR. These results raise questions about potential rent seeking activities of the regulator’s employees.

Wait. Do you mean that Securities and Exchange Commission employees are humans like anybody else, driven by their own sense of greed? Amazing.

A few absolutely striking facts were listed in this paper. The SEC lacked a system to monitor employees’ trades until… 2009. Despite the system implemented early 2009, employees seem to be able to avoid large losses by selling their holdings just before a negative SEC decision is announced. Moreover, previous research also found that politicians and congressmen benefited from insider trading… A law was passed in… 2012 to prevent them from trading on privileged information. 2012! They must be kidding. How late is that?! The logic seems to be: impose red tape on corporations ASAP but please do not affect rent-seeking and other benefits of government officials! The effectiveness of the law still has to be researched…

For sure there are some limitations to this paper and its methodology: the authors only effectively analysed 7,200 transactions out of a total of 29,081. This is because many transactions had invalid tickers (some were mutual funds but… how is even this possible for other securities?), were not traded on American exchanges or had very limited data due to illiquidity. Moreover, they couldn’t identify individual employees and as a result worked on an aggregate portfolio. It is also fair to admit that the ‘abnormal return on short positions’ actually didn’t generate any profit but only prevented losses, as they were not short sales but outright ones.

Still, independently of our view of insider trading (many people argue that it isn’t such a bad thing after all), such results are significant and should be further researched. Regulators like to portray themselves as being on a moral high ground, shaming those guilty of insider trading and other frauds. So the news that they may well succumb to the same temptation as those vulgar and immoral capitalist insiders not only sounds very ironic but also reaches extreme levels of cynicism.

As Lars said:

Who is regulating the regulators?

Some ‘good’ principles of financial regulation

Readers of this blog know the extent of my love for banking regulation. I love regulation. I really do. Otherwise I wouldn’t have much to write about.

Irony aside, I recently read a very good paper by Calomiris (Financial Innovation, Regulation, and Reform, 2009, which you can find here) that made me give regulation a rethink (to be frank, I was disappointed that there’s not much about financial innovation in this paper, but the rest is pretty good).

Calomiris is a free-market guy. He makes it clear is most of his papers, this one included:

The risk-taking mistakes of financial managers were not the result of random mass insanity; rather they reflected a policy environment that strongly encouraged financial managers to underestimate risk in the subprime mortgage market. Risk-taking was driven by government policies; government’s actions were the root problem, not government inaction.

He is right. But he also seems to be a ‘realist’ (if ever this really means anything). He considers that, given our current distortive institutional framework, the best thing we can do is to mitigate its effect through proper regulation. He writes:

If there were no governmental safety nets, no government manipulation of credit markets, no leverage subsidies, and no limitations on the market for corporate control, one could reasonably argue against the need for prudential regulation. Indeed, the history of financial crises shows that in times and places where government interventions were absent, financial crises were relatively rare and not very severe.

[…But] it is not very helpful to suggest only regulatory changes that are very far beyond the feasible bounds of the current political environment. […] Absent the elimination of [all the policies described above], government prudential regulation is a must.

In a way, he has a point. Whereas I’d like to see the implementation of a free banking system, I also have to admit that this possibility is pretty unlikely to ever reoccur (unless a once in a thousand years financial collapse suddenly strikes). Which led me to think about a ‘second best’. This ‘second best’ solution should follow the principles I described here (where I argued in favour of a stable rule set and regulatory framework) and here (where I agreed with Lars Christensen and John Cochrane and argued against macro-prudential regulations). This is what I wrote:

Stable rules are a fundamental feature of intertemporal coordination between savers and borrowers, between investors and entrepreneurs. In order for economic agents to (more or less) accurately plan for the future, for entrepreneurs to develop their business ideas and anticipate future demand, for savers to invest their money and know that their property rights are not going to disappear overnight and accordingly plan their own delayed consumption and provide entrepreneurs with directly available funds, the economic system needs a stable and predictable rule framework. Production and investments take time and as a result involve uncertainty, which should not be exacerbated by an instable rule set. The rule of law is part of this framework. Monetary policy, financial regulation and government policies should follow the same pattern, instead of being discretionary.

What I am about to describe is a non-exhaustive list of ‘good’ principles of regulation that fit (to an extent) a free-market framework. I may update the list over time. Following the principles above, and even though not perfect, a ‘second best’ solution would have to be:

- As least distortive as possible (i.e. introducing as few loopholes and incentives to game the rules as possible)

- As stable as possible (i.e. no discretionary powers), and

- As simple, transparent and clear as possible (i.e. a few clear and straightforward rules are better than a multitude of obscure and complex ones)

On the monetary policy side, despite its flaws, NGDP targeting seems to be the only ‘easily implementable’ policy that meets the three criteria. I won’t discuss it here (see The Money Illusion, The Market Monetarist, Worthwhile Canadian Initiative, and many other blogs for more information). On the slightly ‘less easily implementable’ side, the ‘productivity norm’ would nonetheless be an even better alternative (see George Selgin’s implementation here, from page 64 onwards).

What about financial and banking regulation? In order to respect the three fundamental rules described above, regulators should:

- Define few transparent, straightforward limits and ratios based on objective and easily measurable criteria that are neither pro- nor counter-cyclical

- Not impose their own perception of risk to the market

- Not vary regulatory limits and requirements over time

- Not publicly shame financial institutions that respect regulatory requirements even if borderline-compliant: the regulators’ role is to make sure that institutions respect the requirements, period

- Publicly make clear that regulations only represent minimums, that regulators are only here to make those minimums respected, and that it is the role of market actors to identify stronger from weaker institutions within those regulatory-defined limits

- Not interfere with financial institutions’ strategy and internal organisational structures: harmonising business models takes the risk of weakening the whole system

- Refrain from making any comment unrelated to the (non)compliance of institutions to regulatory requirements

- Allow the market process to run its course and not institutionalise moral hazard by implementing bailout and other backstop mechanisms

Banking regulation is divided into micro-prudential and macro-prudential regulation. The former provides individual banks with rules they have to respect at all times, independently of the performance of the whole economy. The latter provides all banks with rules that vary according to the state of the economy, independently of the performance of each bank. Following the principles above, fixed and straightforward sets of micro-prudential regulations may be acceptable. On the other hand, most macro-prudential regulations would be eliminated given their discretionary component and their variability over time. It is indeed very hard for regulators to identify bubbles and other excesses (see White, 2011, here). They have a poor track record at it. Discretion could well prevent a bubble from growing too much but it could also prevent a genuinely growing market to reach its full potential. Regulators suffer from the central planner’s problem. As Hayek said in his essay The Use of Knowledge in Society:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess.

I can already hear the rebuttals: “but counter-cyclical macro-prudential policies would help mitigate the bust after the boom!” To which I would respond: “how do you identify a ‘boom’?” For a bust to occur, a boom must be unsustainable. Solid and sustainable growth may well happen and should not be interfered with by counter-cyclical regulations that would in fact not be counter-cyclical at all in this case. Nominal stability is primarily the role of monetary policy, which should promote a stable framework to the real economy. An unsustainable boom is likely to emanate from nominal instability. The goal of regulation is not to mitigate the effects of destabilising monetary policies.

Of course, this does not mean that one should not strive to reduce political and regulatory distortions. ‘Idealists’ (if ever this also means anything) are a necessary part of a healthy democratic process. Moreover, too much compromise can be dangerous: where to fix the limit? Because the very distortive sources are still present, crises can still occur and provide extra arguments to further expand the regulatory burden.

PS: I’ll provide examples of regulations that comply or not with those principles in a subsequent post. This post would have been too long otherwise!

Bundesbank’s Dombret has strange free market principles

Andreas Dombret, member of the executive board of the Bundesbank, made two very similar speeches last week (The State as a Banker? and Striving to achieve stability – regulations and markets in the light of the crisis). When I started to read them, I was delighted. Take a look:

If one were to ask the question whether or not the market economy merits our trust, another question has to be added immediately: “Does the state merit our trust?”

[…]

Sometimes it seems as if we are witnessing a transformation of values and a redefinition of fundamental concepts. The close connection between risk-taking and liability, which is an important element of a market economy, has weakened.

Conservative and risk-averse business models have become somewhat old-fashioned. If the state is bearing a significant part of the losses in the case of a default of a bank, banks are encouraged to take on more risks.

[…]

[High bonuses and short-termism] are the result of violated market principles and blurred lines between the state and the banks. They are not the result of a well-designed market economy but rather indicative of deformed economies. However, the market economy stands accused of these faults.

Brilliant. I was just about to become a Dombret fan when…I read the rest:

In my view, the solution is to be found in returning the state to its role of providing a framework in which the private sector can operate. This means a return to the role the founding fathers of the social market economy had in mind.

They knew that good banking regulation is a key element of a well-designed framework for a well-functioning banking industry and a proper market economy in general.

[…]

This is where good bank capitalisation comes into play. It is the other side of the coin. Good regulation should directly address the key problem. If the system is too fragile, an important and direct measure to reduce fragility is to have enough capital.

[…]

Good capitalisation will have the positive side effect of reducing many of the wrong incentives and distortions created by taxpayers’ implicit guarantees and therefore making the bail-in threat more credible ex ante.

And from the second article:

In view of all this, I believe that two elements will be especially important in making banks more stable: capital and liquidity. Deficits in both of these things were factors which contributed significantly to the financial crisis. The state can bring in regulation to address these deficits, and has done so very successfully.

And on shadow banking:

In terms of financial stability, the crux of the matter is that these entities can cause similar risks to banks but are not subject to bank regulation.And the shadow banking system can certainly generate systemic risks which pose a threat to the entire financial system.

Much the same applies to insurance companies. Although they aren’t a direct component of the shadow banking system, they can also be a source of systemic risk. All of this makes it appropriate to extend the reach of regulation.

Sorry but I will postpone joining the fan club…

Mr. Dombret correctly identifies the issue with the financial system: too much state involvement. What is his solution? More state involvement. It is hard to believe that one person could come up with the exact same solution that had not worked in the past. Were the banks not already subject to capital requirements before the crisis? Even if not ‘high’ enough they were still higher than no capital requirement at all. So in theory they should have at least mitigated the crisis. But the crisis was the worst one since 1929, and much worse than previous ones during which there were no capital requirements. Efficient regulation indeed…

Like 95% of regulators, he makes such mistakes because of his (voluntary?) ignorance of banking history. A quick look at a few books or papers such as this one, comparing US and Canadian banking systems historically, would have shown him that Canadian banks were more leveraged than US banks on average since the early 19th century, yet experienced a lot fewer bank failures. There is clearly so much more at play than capital buffers in banking crises…

Moreover, he views formerly ‘low’ capital requirements as a justification for bankers to take on more risks to generate high return on equity. This doesn’t make sense. For one thing, the higher the capital requirements the higher the risks that need to be taken on to generate the same RoE. It also encourages gaming the rules. This is what is currently happening, as banks are magically managing to reduce their risk-weighted assets so that their regulatory-defined capital ratios look healthier without having to increase their capital.

Mr. Dombret starts by seriously questioning the state’s ability to manage the system and highlights the very harmful and distortive effects of state regulation to eventually… back further and deeper state regulation.

A question Mr. Dombret: what are we going to do following the next crisis? Continue down the same road?

Can please someone remind Mr. Dombret of what a free market economy, which he seems to cherish, means?

Picture: Marius Becker

We are now in a micromanaged economy

Interesting piece from Matt Levine on Bloomberg on Wednesday. It highlights how far regulators are now going to micromanage the financial system. They now prevent banks from lending to private equity firms (so-called ‘leveraged loans’), distorting lending mechanisms, market pricing and economic agents’ learning process. The whole scheme is subject to potential arbitrage and could possibly lead to even more devastating opaque financial engineering.

Some of my friends (senior bankers working in financial institutions mergers and acquisitions at other banks) recently told me that regulators prevent their clients (banks) from trying to acquire any other banks. Nonetheless, during the crisis, regulators almost forced, or at the very least engineered, banks mergers…Does anybody still believe we are in a free market?

This is a regulator:

The impact on private equity, a significant driver of what we see as risky practices, is an intended consequence of our actions,” Martin Pfinsgraff, the OCC’s senior deputy comptroller for large-bank supervision, said in an interview. “As regulators, we certainly hope to change bad practices and remove the extraordinary froth that’s experienced at the peak of a credit cycle. If we can mitigate that, it reduces the size of the valley to follow.

A suggestion to this person: why don’t you become a banker? It looks like you know better than bankers how to safely pick counterparties to lend to. Moreover, what he does not realise is that by restraining the flow of credit somewhere, it’s going to reappear somewhere else, shifting systemic risk to another (and possibly darker) corner of the economy.

Forcing banks: to add a bit of capital there and there and some liquidity here, to consider which assets are safe and liquid and which aren’t, to trade some products through specific counterparties, not to acquire competitors, to force the acquisition of competitors, and so on, was not enough. Regulators have now introduced another new tool and earned another power. Moreover, in their quest to make the banking system ‘safer’, regulators are likely to make it more vulnerable: banks will become less differentiated, holding the same types of assets, lending to the same types of clients, having the same types of internal models and engaged in the same types of trading activities. I let you guess what happens when those regulatory-favoured activities collapse.

Exactly 70 years after Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom was published, it looks like we’re back to the same point.

Photo: HR People

A UK housing bubble? Sam Bowman doubts it

On the Adam Smith Institute’s blog, Sam Bowman had a couple of posts (here and a follow-up here, and mentioned by Lars Christensen here) attempting to explain that there might not have been any house price bubble in the UK. He essentially says that there was no oversupply of housing in the 1990s and 2000s. Here’s Sam:

These charts show that housing construction was actually well below historical levels in the 1990s and 2000s, both in absolute terms and relative to population. It is difficult to see how someone could claim that the 2008 bust was caused by too many resources flowing toward housing and subsequently needing time to reallocate if there was no bubble in housing to begin with.

What this suggests is that the Austrian story about the crisis may be wrong in the UK (and, if Nunes’s graphs are right, the US as well). The Hayek-Mises story of boom and bust is not just about rises in the price of housing: it is about malinvestments, or distortions to the structure of production, that come about when relative prices are distorted by credit expansion.

Well, I think this is not that simple. Let me explain.

First, the Hayek/Mises theory does not apply directly to housing. In the UK, there are tons of reasons, both physical and legal, why housing supply is restricted. As a result, increased demand does not automatically translate into increased supply, unlike in Spain, which seems to have lower restrictions as shown by the housing start chart below:

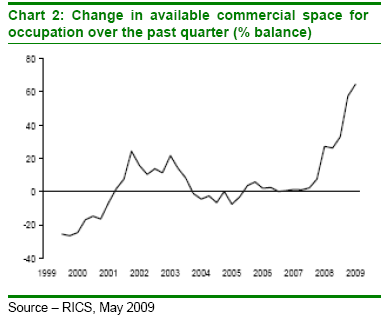

Second, Sam overlooks what happened to commercial real estate. There was indeed a CRE boom in the UK and CRE was the main cause of losses for many banks during the crisis (unlike residential property, whose losses remained relatively limited).

Third, the UK is also characterised by a lot of foreign buyers, who do not live in the UK and hence not included in the population figures. Low rates on mortgages help them purchase properties, pushing up prices, triggering a reinforcing trend while supply in the demanded areas often cannot catch up.

Fourth, the impact of Basel regulations seems to be slightly downplayed. Coincidence or not, the first ‘bubble’ (in the 1980s) appeared right when Basel’s Risk Weighted Assets were introduced. And it is ‘curious’, to say the least, that many countries experienced the same trend at around the same time. Would house lending and house prices have increased that much if those rules had never been implemented? I guess not, as I have explained many times. I have yet to write posts on what happened in several countries. I’ll do it as soon as I find some time.

I recommend you to take a look at my RWA-based Austrian Business Cycle Theory, which seems to show that, while there should indeed be long-term real estate projects started (depending on local constraints of course), there is also an indirect distortion of the capital structure of the non-real estate sector.

While there may well be ‘real’ factors pushing up real estate prices in the UK, there also seems to be regulatory and monetary policy factors exacerbating the rise.

- Chart 1: Spanish Property Insight

- Chart 2: FT Alphaville

- Chart 3: Guardian

Risk-weighted assets and capital manipulations

As some of you might have noticed, the Bank of International Settlements published yesterday the final version of the Basel III leverage ratio (official report can be found here). This ratio is a measure of the capitalisation of a bank for regulatory purposes. I have already mentioned a few times those capital ratios. Since the first Basel regulations were introduced, capital ratios were based on risk-weighted assets (RWAs). Some of you might already be aware of my ‘love’ of RWAs… The leverage ratio, on the other hand, gets rid of RWAs.

I am not going to speak about the leverage ratio here. But about other two other related BIS studies that, in a way, legitimate the use of unweighted capital ratios. In January 2013, the BIS published a first analysis of market RWAs. They tried to estimate the variability of risk-weights associated to equivalent securities across banks. The BIS provided 26 portfolios of financial securities to 16 different banks and asked them to risk-weigh them according to their internal models. The results were shocking (but not surprising).

Banks mostly assess market risks using statistical Value-at-Risk models. The graph below shows the dispersion of the results provided by the banks’ VaR models. The results are normalised so that the median result is centred on 100%.

The dispersion is huge. Some banks judged portfolio 14 as being around 1000% riskier than the median bank’s perception of it (and I am not even talking about the most conservative one). Some comfort could be taken from the diversified portfolios (25 and 26), which are closer to real life portfolios. Nonetheless, even in those, variations are large enough to undermine the credibility of the risk-weights applied to them. The chart below demonstrates the capital requirements (in Euros) implied from the VaR results above for portfolio 25. Some banks would put aside more than twice the amount of capital than others would, for the same portfolio of securities.

The BIS believed at that time that different local regulatory requirements were partially responsible for the results (such as some banks following Basel 2.5 and others Basel 2. I’m going to skip the details but Basel 2.5 pushes market RWAs up).

The BIS eventually published its final study on market RWA at the end of December. This time, all banks had implemented Basel 2.5. So most of the observed variation could only come from the banks’ internal model differences. What did they find?

Not much difference. Variations were still huge. The resulting implied capital requirements (in thousands of Euros) for portfolios 29 and 30 were as follows:

Clearly, RWAs are unreliable. This questions the very utility of RWA-based regulatory capital ratios. How can one actually trust two different banks both reporting 10% Tier 1 ratios? One of them might in reality hold twice as little capital as the other one for what is actually the same risk level. Banks can easily game the system. Moreover, the FT was reporting yesterday that some banks were starting to report RoRWA (return on RWAs) instead of more traditional return on equity or return on assets. But those measures suffer from the exact same defects. While an unweighted leverage ratio is clearly not perfect, RWAs introduce far too much information distortion and even potentially exacerbate the business cycle. Time to get rid of them.

“It was approved by regulators”

If ever you needed a single sentence to symbolically prove that today’s financial markets aren’t free, there you go.

You can’t possibly imagine the countless times I’ve heard this, both as part of my various jobs* or in the financial press. The process is pretty much always the following:

- Banking executives privately or publicly denounce regulators as incompetent and/or not understanding much about actual banking practice

- Investors/shareholders/journalists/analysts/other bankers question those executives about a recent, often suspect, change in their internal methodology that allows them to book higher profits/ROE

- Banking executives seriously justify their decision with: “It was approved by regulators”

Let’s clarify something: not all bankers are critical of regulators, and not all bankers are so inconsistent either. Most bankers thrive to do their job correctly and honestly, and believe that their decisions are appropriate and for the long-term benefit of both clients and shareholders.

Nonetheless, regulators have become some bankers’ strongest ally and the easiest justification to bypass market discipline. When shareholders are worried about a new, apparently risky, change in internal models, underwriting criteria or anything else, bankers don’t have to look very far to find a good excuse anymore. Regulators inadvertently become bankers’ best friends.

A typical illustration of that story occurred about a year ago, when Morgan Stanley changed its internal Value-at-Risk-based market risk model, which all of a sudden made its trading book look less risky than it would have been under the previous version of that same model. Many finance professionals and investors were critical of the move. How did Morgan Stanley’s CFO dismiss analysts’ questions?

It’s been approved by regulators.

While she may have been honestly thinking that the new model was better or more appropriate, the use of this argument is unfortunate. This is now the best – and the worst – defence bankers have against crucial free markets’ scrutiny.

*no, no names again, and none of my previous or current firms

European banking resolution non-mechanism

The Financial Times and Zero Hedge had a pretty funny chart today describing the new mechanism to ‘resolve’ a failing bank, agreed yesterday by European ministers:

Zero Hedge calls this the “MinotEur Labyrinth”. As they say, good luck to them.

PS: I might talk about it in more details a later, when I have more time…

Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Some recent empirical evidence

A recent study by academics from the Southern Methodist University and the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania had very interesting findings (the actual full paper can be found here): banks based near booming housing markets charged higher interest rates and reduced loan amounts to companies, which ended up investing less than companies borrowing from banks located in stable (or falling) housing markets. They called this the “crowding-out effect of house-price appreciation”. The study gathered data from 1988 to 2006 in the US, during the Basel period. It would have been interesting to compare with the pre-Basel era and replicate it with European markets.

Conventional economic knowledge seemed to think that “to the extent that home prices begin to rise, consumers will feel wealthier; they’ll feel more disposed to spend…that’s going to provide the demand that firms need in order to be willing to hire and to invest.” (This is Ben Bernanke as quoted by The Economist, which mentioned this study a few weeks ago)

But our academics instead found an inverse relationship:

We estimate that a one standard-deviation increase in housing prices (about $79,700 in year 2000 dollars) that a bank is exposed to decreases investment by firms related to that bank by almost 6.3 percentage points, which is approximately 12% of a standard deviation for firm investment. Banks also increase the interest rate charged by 9 basis points, reduce outstanding loans by approximately 9%, and reduce loan size by approximately 4.5%. These results are consistent with banks reducing the supply of capital to firms in response to increased housing prices.

So much for the Keynesianism of housing bubbles…

Their findings was summarised in an easier to read single chart by The Economist:

I think they are spot on in identifying this crowding out effect but overlook the underlying importance of Basel’s risk-weighted assets in triggering the boom and forcing the reallocation of capital towards housing. In their paper, there is not a single reference to Basel, banks’ capital requirements (apart from one related to MBS) and RWAs. But their story matches almost perfectly the RWA-based ABCT model I described in my previous post on the topic.

What did my model say? That the supply of loanable funds would be reduced to businesses and increased to real estate as a result of capital-optimising choices made by banks (because of RWAs capital constraints). That consequently, interest rates would increase for businesses and be reduced for real estate. This is exactly what they found.

But it doesn’t stop here. The model also said that an increase in interest rates to businesses would shorten their structure of production as interest-sensitive long-term investments become unprofitable. What did they find? That businesses reduced investments despite the temporary boost in consumption due to the well-referenced wealth effects (which they also mentioned)…

However, they missed the deeper implications of banking regulation on the reallocation of capital from businesses to real estate. To them, house price increases seems to be the only factor diverting capital towards housing. I don’t deny that increasing house prices would bring about self-reinforcing house lending, even in a free market: as house prices increase, lending gets facilitated and speculators are attracted, pushing prices up even further. But my point is that regulation and RWAs can both trigger and exacerbate the process way beyond the self-correcting point at which it would normally stop (and collapse) in a free market environment.

There is catch though… If RWAs do indeed trigger a boom in house lending, how could they find some areas in the US within which the process actually wasn’t triggered (no increase in house prices/lending) despite being subject to the same regulatory framework? Well, there are possibly a few answers to that question. Some local banks could actually be in an area experiencing falling house prices for some reason (even though they increase nationally) and low mortgage demand. This would automatically limit the amount they lend and push RWAs on real estate up, making housing less attractive from a capital-optimisation point of view. Another possibility would be that those local banks are actually subsidiaries of other banks that try to optimise capital usage on an aggregate (national) basis. However, it is hard to say as the criteria used to build the sample of banks are not clear.

There is another, simpler, possible explanation: even in falling housing prices areas, local banks’ business lending was still constrained and mortgage lending still supported! Meaning that, in a RWA-free world (and excluding a recessionary environment), a decline in housing prices would have triggered an even sharper decrease/increase in mortgage/business lending. This cannot be proved with this study however. There could also be other explanations that haven’t come to my mind yet.

Overall, I remain slightly sceptical of statistical/regression/correlation-based economic studies and I’ll take this one with a pinch of salt, especially as they use various assumptions and proxies that could easily distort the outcome. Nonetheless, the results they obtained were quite significant. And they provide some empirical evidences to my very theoretical model.

Meanwhile, Nouriel Roubini on Friday, in a piece called Back to Housing Bubbles, listed all the markets in which there are signs of bubbles:

[…] signs of frothiness, if not outright bubbles, are reappearing in housing markets in Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, France, Germany, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and, back for an encore, the UK (well, London). In emerging markets, bubbles are appearing in Hong Kong, Singapore, China, and Israel, and in major urban centers in Turkey, India, Indonesia, and Brazil.

Real estate bubbles existed before Basel introduced risk-weighted assets, but nothing on that scale and in so many countries at the same time. Time for policy-makers to wake up.

RWA-based ABCT Series:

- Banks’ risk-weighted assets as a source of malinvestments, booms and busts

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Update

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – A graphical experiment

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Some recent empirical evidence

- A new regulatory-driven housing bubble?

Recent Comments