Carney attacks the ‘pretence of knowledge’ of free markets

Some speeches make you want to scream. Mark Carney’s latest is one of those.

In a recent speech titled Three truths for finance, Carney, the governor of the BoE, explains that those ‘truths’ are in fact ‘lies’, and those three lies are “this time is different”, “markets always clear”, “markets are moral”. Where to start?…

According to Carney:

The first lie is the four most expensive words in the English language: “This Time Is Different.”

I can only agree with Carney here. He continues:

This misconception is usually the product of an initial success, with early progress gradually building into blind faith in a new era of effortless prosperity.

He mentions the pre-crisis debt bubble, which ‘financial innovation’ and a ‘ready supply of foreign capital from the global savings glut’ made cheaper. Yet he never mentions central banks’ policies, which kept interest rates low over the whole period, or the fact banking regulation was the very reason behind the cheap credit supplied to a few particular sectors of the economy or also the fact that high saving rates in countries such as China mostly financed high investment rates in the same countries. No, this is due to private actors’ irrationality, who of course believed that this time was different.

But Carney’s logic is faulty. Over the recent years, it is him, and his fellow central bankers, who have kept arguing that “this time was different”, and that we needed to maintain interest rates below the lowest levels ever recorded in human history.

It gets worse when Carney mentions the second ‘lie’, which reveals his deep Keynesian thinking:

Beneath the new era thinking of the Great Moderation lay a deep-seated faith in the wisdom of markets. Policymakers were captured by the myth that finance can regulate and correct itself spontaneously. They retreated too much from the regulatory and supervisory roles necessary to ensure stability.

That “markets always clear” is the second lie, one which gave rise to the complex financial web that inflated the debt bubble.

In markets for goods, capital, and labour, evidence of disequilibria abounds.

In goods markets, there is ‘sluggishness everywhere’. Left to themselves, economies can go for sustained periods operating above or below potential, resulting, ultimately, in excessive or deficient inflation.

He adds:

If markets always clear, they can be assumed to be in equilibrium; or said differently “to be always right.”

First, it is clear that Carney does not understand the dynamic entrepreneurship process that characterises a capitalist economy. Equilibrium does not exist, and markets are in constant fluctuations as entrepreneurs and investors try to identify and benefit from what they perceive as mispricings and profit opportunities (see Israel Kirzner). Equilibrium is at best a theoretical construct, and most economists (mainstream or not) who have studied entrepreneurship and markets know this. In short, the market is a dynamic price discovery mechanism.

As a result, accusing markets of not being in equilibrium completely misses the points of having markets in the first place. If markets are in equilibrium, there is no need to act anymore. No need to come up with new ideas, create and invest.

Second, he mentions financial innovations and their effects as if they had existed in a vacuum, independently of any sort of regulation incentivising their use and distorting market outcomes. But it would mean admitting that policymakers can be dead wrong. Possibly not the message he is trying to convey.

It gets absurd when Carney uses the phrase ‘pretence of knowledge’ (his emphasis):

More often than not, even describing the universe of possible outcomes is beyond the means of the mere mortal, let alone ascribing subjective probabilities to those outcomes.

That is genuine uncertainty, as opposed to risk, a distinction made by Frank Knight in the 1920s. And it means that market outcomes reflect individual choices made under a pretence of knowledge.

I have to applaud. Carney, a Keynesian, used Hayek’s Nobel speech title, to express the exact opposite of Hayek’s idea. In his 1974 speech, Hayek explains that central planners attempting to control the economy were victim of a pretence of knowledge, because it was impossible for them to be aware of all the ‘particular circumstances of time and place’ (a phrase that he uses in most of its post-WW2 literature). Only the private market actor, who was in direct connection to his local market, could attempt to come up with the solution that satisfied the demand expressed by this market.

Yet Carney turned Hayek’s reasoning on its head. According to Carney, it is private market actors who demonstrate this pretence of knowledge as they believe they know what is right for them or what the market actually demands! He seems to assume (wrongly) that economic agents believe they are omniscient and not aware of the uncertainty inherently linked to the economic decisions they take.

Hayek would turn in his grave. He would probably tell Carney that market outcomes are the result of millions of individuals who acted on different assumptions, different risk-assessments, different knowledge and skillsets, and that this is the aggregation of all those various local variables that lead to a market outcome that can more efficiently coordinate dispersed knowledge, skills and demand than any central authority ever can. He would probably add that Carney keeps mentioning market failures without ever referring to most of the reasons underlying those failures, that is, artificial restrictions and distortions that originate in government activity (…and central banks…).

But Carney is likely to never admit such things as he is no free-market lover:

In the end, belief in the second lie that “markets always clear” meant that policymakers didn’t play their proper roles in moderating those tendencies in pursuit of the collective good.

And how would you even know how to ‘moderate’, or simply how to identify, those negative tendencies, Mr Carney? And how do you define what this so-called ‘collective good’ is? ‘Pretence of knowledge’ you said?

He then insists (his own emphasis, which says a lot):

Despite these shortcomings, well-managed markets can be powerful drivers of prosperity.

Carney’s last ‘lie’, that markets are moral, suffers from a lack of arguments. He seems to base most of his ‘markets are amoral’ rhetoric on recent examples of price-fixing in a number of rates and commodities markets. He is right that fraud is reprehensible. Yet, in those cases, it was not markets that were to blame, but a few abusers who tried to benefit at the expense of the markets. Here again Hayek would argue that there is nothing more ‘moral’ than unhampered markets that distribute services to those that need them and reward those that provide them, within the framework of the rule of law.

At the end of his speech, Carney introduces the recent BoE initiative to open a forum on re-building ‘real markets’ (his emphasis again). You want ‘real’ markets Mark? Just release them from their constraints. It’s as simple as that.

Financial knowledge dispersion and banking regulation

I have never hidden my admiration for Hayek’s work, in particular over the last few weeks. The name of this blog is itself derived from Hayek’s concept of spontaneous order. I view Mises as having laid the foundations of a lot of Hayek’s and modern Public Choice theory thinking (see Buchanan’s admission that Mises “had come closer to saying what I was trying to say than anybody else”). He was to me a more comprehensive theorist than Hayek, and made us understand through his methodological individualism method that human action was at the heart of economic behaviour. But Hayek’s brilliant contribution is to have built on Mises’ business cycle, market process and entrepreneurship insights to develop a coherent and deep philosophical, legal, political and economic paradigm. While some would argue that he didn’t push his logic far enough (see here or here), it remains that reading the whole body of Hayek’s work is truly fascinating and enlightening. It suddenly feels like everything is connected and that “it now all makes sense”.

Some of Hayek’s insights are verified on a day-to-day basis. He repeatedly emphasised that knowledge was dispersed throughout the economy and that no central authority could ever be aware of all the ‘particular circumstances of time and place’ in real time. This knowledge problem was core to his spontaneous order theory, which describes how market actors set up plans independently of each other according to their needs and coordinated through the price system and respect for the ‘meta-legal’ rules (what he later called ‘rules of just conduct’) of the rule of law.

I have very recently offered a critique of macro-prudential regulation based on Hayek’s and Public Choice’s insights. But his description of the knowledge problem also applies. Zach Fox, on SNL (link gated), reports that the whole of macro-prudential regulatory framework may be useless because the US agency in charge of tracking the data can only access outdated, if not completely wrong, datasets. This agency calculates ‘systemic risk’ scores from a number of data points sent by various banks. Problem: those figures keep being revised by many banks, sometimes radically, leading to large fluctuations in ‘systemic risk’ scores and regulators keep using outdated data:

SNL has only been able to track the movements by scraping each bank’s individual filing periodically over the last year. U.S. banks filed their 2013 systemic risk reports by July 2014, at which point SNL reported on the data. After noticing some differences, SNL followed up Jan. 13, 2015. In total, 12 data points had changed across the filings for eight different banks. Then, in July 2015, SNL noticed yet more revisions to the 2013 filings.

Fox concludes:

When a bank’s derivative exposure shrinks by $314 billion — roughly half the size of Lehman when it filed bankruptcy — it raises questions about the company’s ability to model accurately in real-time. When that change does not come until 16 months after the initial filing, it raises questions about the Fed’s vigilance. And when the government’s office established to track systemic risk uses incorrect, outdated data, it raises questions about the entire theory of macroprudential supervision.

(one could add: “and of micro-prudential supervision”)

In short, due to dispersed nature of financial knowledge (i.e. data) across the whole banking sector and the inherently bureaucratic nature of the data collection and analysis process, regulatory agencies do not have ability to collect accurate data in a timely manner, and hence act when really necessary.

Of course, some banks also seem to struggle to report the required data. But they are much closer to their own ‘particular circumstances of time and place’ and hence can take action way before the data even reach the regulator. Moreover, banks are organisations that comprise several layers of individuals, each of them facing their own particular circumstances. Knowledge is dispersed among bankers who deal with clients on a daily basis and goes up the hierarchical chain if and when necessary. Governmental agencies are at the very end of this chain and informed last, way after the actions have taken place (or the disaster occurred).

Of course, this does not mean that commercial banks are always effective in dealing with data and that all their decisions are taken rationally. But a central regulatory agency would not have the ability to make the bank safer either. Forcing banks to adopt certain standards in advance could help solve the problem to an extent only, as circumstances vary and standards may not be appropriate for all situations or could even exacerbate problems as I keep emphasising on this blog (and are likely to be a harmful and unnecessary drag on economic performance).

PS: The Chinese central bank is about to cut reserve requirements to boost lending according to the WSJ. Clearly China hasn’t been infected by the MMT/endogenous money virus yet.

PPS: Kinda related to this post, but definitely related to this blog, see this Hayek’s quote of the day:

Above all, however, I am bound to stress that in the course of the work on this book I have been, by the confluence of political and economic considerations, led to the firm conviction that a free economic system will never again work satisfactorily and we shall never remove its most serious defects or stop the steady growth of government, unless the monopoly of the issue of money is taken from government. I have found it necessary to develop this argument in a separate book, indeed I fear now that all the safeguards against oppression and other abuses of governmental power which the restructuring of government on the lines suggested in this volume are intended to achieve, would be of little help unless at the same time the control of government over the supply of money is removed. Since I am convinced that there are now no longer any rigid rules possible which would secure a supply of money by government by which at the same time the legitimate demands for money are satisfied and the value of that money kept stable, there appears to me to exist no other way of achieving this than to replace the present national moneys by competing different moneys offered by private enterprise, from which the public would be free to choose which serves best for their transactions.

It comes from the chapter 18 of Law, Legislation and Liberty (which I have now read), and highlights a significant evolution in Hayek’s thinking since The Constitution of Liberty, in which he had argued in favour of government managing the money supply (but should do it well of course).

Macro-pru, regulation, rule of law and public choice theory

Another rule of law-related post. It might be the anniversary of the Magna Carta that brought this topic back in fashion. Consider it as a follow-up post to my Hayekian legal principles post of a couple of weeks ago.

John Cochrane has a very long post on the rule of law on his blog (which could have been an academic article as the pdf version is 18-page long) titled The Rule of Law in the Regulatory State.

His vision is a little gloomy, but spot on I believe:

This rule of law always has been in danger. But today, the danger is not the tyranny of kings, which motivated the Magna Carta. It is not the tyranny of the majority, which motivated the bill of rights. The threat to freedom and rule of law today comes from the regulatory state. The power of the regulatory state has grown tremendously, and without many of the checks and balances of actual law. We can await ever greater expansion of its political misuse, or we recognize the danger ahead of time and build those checks and balances now.

He believes the rise of the regulatory state does not fit the standard definitions of socialism, regulatory capture or crony capitalism. He believes that we are

headed for an economic system in which many industries have a handful of large, cartelized businesses— think 6 big banks, 5 big health insurance companies, 4 big energy companies, and so on. Sure, they are protected from competition. But the price of protection is that the businesses support the regulator and administration politically, and does their bidding. If the government wants them to hire, or build factory in unprofitable place, they do it. The benefit of cooperation is a good living and a quiet life. The cost of stepping out of line is personal and business ruin, meted out frequently. That’s neither capture nor cronyism.

He thinks the term ‘bureaucratic tyranny’ could be appropriate to describe the situation, and that it is the ‘greatest danger’ to our political freedom. That is, opposing or speaking out against a regulatory agency, a politician or a bureaucrat might prevent you from obtaining the required regulatory approval to run your business.

He takes what seems to be a Public Choice view when he states that “the regulatory state is an ideal tool for the entrenchment of political power was surely not missed by its architects.”

While his post covers all sorts of industries, and while his definition of the rule of law (and its difference with mere legality) isn’t as comprehensive as Hayek’s, it remains pretty interesting. He actually has a lot to say on the current state of banking and financial regulation:

The result [of Dodd-Frank] is immense discretion, both by accident and by design. There is no way one can just read the regulations and know which activities are allowed. Each big bank now has dozens to hundreds of regulators permanently embedded at that bank. The regulators must give their ok on every major decision of the banks.

While he says that, for now, Fed staff involved in bank stress tests are mostly honest people, he is wondering how long it will take before the Fed (pushed by politicians or not) stop resisting the temptation to punish particular banks by designing stress tests (whose methodology is undisclosed) to exploit their weaknesses.

While Cochrane laments the rise of discretionary ruling and its consequences on freedom, The Economist also just published a warning, albeit a less-than-passionate one. Since the crisis, The Economist has always taken a somewhat ambivalent, if not completely contradictory double-stance (for instance, it takes position against rules in monetary policy in the same weekly issue). Here again, the newspaper believes that the crisis made new rules ‘inevitable’, because taxpayers ‘need protection from the risks of failure’. And that, as a result, regulators needed ‘flexible’ rules (MC Klein made a similar point some time ago – see my rebuttal here).

By and large, The Economist has approved that sort of rulemaking, as well as the use of macro-prudential policies (something I have regularly criticised on this blog). Nevertheless, the newspaper also complains about abuse of discretionary decision-making and the effect of regulatory regime uncertainty (a term originally coined by Robert Higgs). It doesn’t seem to have realised that the nature of what it was requesting (i.e. respect of the rule of law and control of the industry and of the monetary system by regulatory agencies) was by nature antithetical. Cochrane’s fears (as well as mine) thus seem justified if such a classical liberal newspaper cannot even realise this simple fact.

Public Choice theory could be used as a strong rebuttal to the regulatory discretion rationale. As Salter points out in a remarkable paper titled The Imprudence of Macroprudential Policy, the economic and political science behind discretionary macro-pru policies taken by bureaucratic agencies suffers from major flaws that regulators or academics haven’t even tried to address.

He highlights the fact that, as Mises and Hayek had already mentioned decades ago during the socialist calculation debate, regulatory agencies lack the information signalling system to figure out what the ‘right’ market price should be and hence act in the dark, possibly making the situation even worse* (and empirical evidences do show that it doesn’t work), and that the assumption of the macro-pru literature that capitalist (and financial) systems are inherently unstable is at best unproven. A typical example is Basel’s capital requirements: as I have long argued on this blog, RWAs incentivise the allocation of credit towards asset classes that regulators deem safe. The fact that they are aware of the allocative power that they have is clearly illustrated by the recent news that EU regulators would lower capital requirements on asset-backed securities to persuade insurance firms to invest in them! Yet they continue to blame banks for over-lending for real estate purposes and not enough ‘to the real economy’. Go figure.

Worse, Salter continues, macro-pru regulation (and his critique also applies to all other regulatory agencies) assumes away all Public Choice-related issues, taking for granted omniscient regulators always acting in the ‘public interest’. Yet proponents of strong regulatory agencies seem to ignore (voluntarily or not – rather voluntarily if we believe Cochrane) that regulatory agencies themselves can fall prey to the private interests of regulators, whether those are power, money, job… If not directly to the regulators, regulatory agencies can fall prey to voters’ irrationality, as Caplan would argue (but also Mises and Bastiat), leading elected politicians to put in place regulators executing the irrational wishes of the voters. The resulting naïve line of thought of the macro-pru and regulatory oversight school is dangerous and goes against the body of knowledge that Western civilization has accumulated since the Enlightenment period.

And such occurrences are not only present in the minds of Public Choice theorists. They are happening now. The case of the head of the British Financial Conduct Authority directly comes to mind: whether or not one agreed with his “shoot first, ask questions later” method (and many didn’t), he was removed from office by the new UK government as he didn’t fit in the new political ‘strategy’.

What can we do? Cochrane proposes a Magna Carta for the regulatory state, in order to introduce the checks and balances that are currently lacking in our system (for instance, appeals are often made with the same regulatory agency that took the decision in the first place). Buchanan would certainly argue for a similar constitutional solution that would attempt a return to the ‘meta-legal’ principles of the rule of law described by Hayek, with an independent judiciary as the main arbitrator.

The wider public certainly isn’t ready to accept such changes given its negative opinion of particular industries (they’d rather see more regulatory oversight). Consequently, the only way to convince them that constitutional constraints on regulatory agencies are necessary seems to me to remind them that regulatory discretion negatively affects them as well (and day-to-day examples of incomprehensible regulatory decisions abound). If broad principles can be agreed upon from the day-to-day experience of millions of people, they should apply more broadly to all types of sectors. As Salter concludes for macro-prudential policies (although it applies to any regulatory agency):

Market stability is ultimately to be found in institutions, not interventions. Institutions that are robust to information and incentive imperfections must be at the heart of the search for stable and well-functioning markets. Robust monetary institutions themselves depend on adherence to the rule of law and the protection of private property rights, which are the cornerstone of any well-functioning market order. Since macroprudential policy relies on unjustifiably heroic assumptions concerning the information and incentives facing private and public agents, its solutions are fragile by construction.

*Cowen and Tabarrok take another angle here by arguing that the problem of ‘asymmetric information’, which underlies most regulatory thinking, almost no longer exists in the information/internet age.

Hayekian legal principles and banking structure

The latest CATO journal contains a truly fascinating article (at least to me) of George Selgin titled Law, Legislation, and the Gold Standard. Selgin roots his arguments in Hayekian legal theory, as developed by Hayek in his books The Constitution of Liberty and Law, Legislation and Liberty*.

Hayek differentiates ‘law’ (that is, general backward-looking ‘meta-legal’ rules that follow the principle of the rule of law) from forward-looking ‘legislation’, which is unfortunately too often described as ‘law’ despite not respecting the very fundamentals of the rule of law. As such, Hayek describes the rule of law as being

a doctrine concerning what the law ought to be, concerning the general attributes that particular laws should possess. This is important because today the conception of the rule of law is sometimes confused with the requirement of mere legality in all government action. The rule of law, of course, presupposes complete legality, but this is not enough: if a law gave the government unlimited power to act as it pleased, all its actions would be legal, but it would certainly not be under the rule of law. The rule of law, therefore, is also more than constitutionalism: it requires that all laws conform to certain principles.

Therefore, the rule of law, according to Hayek, relies on general ‘meta-legal’ rules that have progressively, spontaneously, if not tacitly, been discovered and evolved in a given society to facilitate social interactions and exchanges between individuals (“a government of law and not of men”). Those custom-based rules have certain attributes, namely that they be “known and certain”, apply equally to everyone, define a clear limit to the coercive power of government, require the separation of power and finally only allow the judiciary to exert discretionary rulemaking (within the boundaries of those meta-legal rules). Hayek explains that “under a reign of freedom the free sphere of the individual includes all action not explicitly restricted by a general law.”

Within this framework, Selgin describes the appearance of the gold standard as following the generic principle described by Hayek:

The difference between private or customary law and public law or legislation is, I submit, one of great importance for a proper understanding of the gold standard’s success. For, despite both appearances to the contrary and conventional wisdom, that success depended crucially upon the gold standard’s having been upheld by customary law rather than by legislation. It follows that any scheme for recreating a durable gold standard by means of legislation calling for the Federal Reserve or other public monetary authorities to stand ready to convert their own paper notes into fixed quantities of gold cannot be expected to succeed.

According to him, the gold standard and its definition was mostly a spontaneous monetary arrangement rooted in private commercial customs, and enforced through the private law of contracts. He sums up:

In short, countries abided by the rules of the gold standard game because that game was played by private citizens and firms, not by governments.

Consequently, a gold standard put in place and enforced by governments is unlikely to work. He continues:

Although it may seem paradoxical, our understanding of the classical gold standard suggests that, if that standard had been deliberately set up by governments to enhance their borrowing ability, it is unlikely that it would have worked as intended. This conclusion follows because, once public (or quasi-public) authorities, governed by statute law rather than the private law of contracts, become responsible for enforcing the rules of the gold standard game, the convertibility commitments crucial to that standard’s survival cease to be credible.

He, as a result, doubts about the ability of the gold standard to be ‘forced’ to return through government policy, and demonstrates that post-WW1 attempts to reinstate the gold standard were doomed from the start as states “tragically misunderstood the true legal foundations” of the famous 19th century monetary arrangement. But Selgin also believes that a ‘spontaneous’ return to gold would be unlikely because the public has been ‘locked-into’ a fiat money standard, and that customary law tends to reinforce that trend – by legitimizing the practice over time – rather than providing a way out. Moreover, he concludes, if a new commodity-like standard were to emerge, nothing guarantees that it wouldn’t be based on another sort of medium (including synthetic commodities such as cryptocurrencies).

Now that I have explained the basics of Selgin’s reasoning, I will try to understand what it involves for banking structure and regulation. While free banking systems, such as Scotland’s, have arguably spontaneously evolved following a custom-based legal framework, the structure of the whole of today’s financial system comprises barely anything ‘natural’ left, as Bagehot would point out. Banking, as we know it, is a pure product of decades, if not centuries, of accumulating layers of positive legislation and government discretionary policies. In short, there is now little overlap between banking and the rule of law**.

The inherent instability of banking systems regulated by statute-based law, as opposed to the relative stability of free banking systems (which Larry White referred to as ‘anti-fragile banking and monetary systems’), is therefore unsurprising seen through Hayek’s and Selgin’s lens: governments, even with the best of all possible intentions, could simply not come up with a banking arrangement that could outperform decades or centuries of experience and decentralised knowledge gains that were reflected in rule of law-compliant free banking. Their attempt at centralising and harmonising the “particular circumstances of time and place” were self-defeating.

But the question isn’t what’s wrong about today’s financial system, but can we do anything about it? Can we get back to a rather ‘pure’, rule of law-compliant, free banking system? And my answer is, unfortunately, rather Bagehotian: despite how much I wish to witness the re-emergence of a financial structure based on laissez-faire principles, I believe it’s unlikely to happen… (but wait, there’s a new hope)

Why? For the very reason mentioned by Selgin: regulations have shaped the financial structure for such a long time that innovations and practices have been established that seem now unlikely to disappear. Let me give two examples:

- Money market funds were originally created to bypass the US regulation Q, which has since then been abolished. But MMF are still major financial players and unlikely to disappear any time soon. They have become an established part of the financial structure.

- Mathematical model-based risk frameworks, which existed before the introduction of Basel regulations but were not as widespread, and certainly not as uniform. Basel rules and domestic regulators required common standards that are now used both by analysts and commentators as data, and by bankers for internal risk, capital and liquidity management purposes, despite their limitations and the distortion they insert into the decision-making process. Abolishing Basel and its local implementations (such as CRD4 or Dodd-Frank) are unlikely to remove what is now accepted as market practice. However, less uniformisation in models and uses are likely to appear over time.

What about the very basic component of our modern banking system, the main beneficiary of statutory law, namely the central bank? Bagehot declared that “we are so accustomed to a system of banking, dependent for its cardinal function on a single bank, that we can hardly conceive of any other”, and opposed a radical transformation of the system which, unfortunately, was there to stay. Yet I believe the probability of getting rid of central banks without causing too much disruption is higher than what Bagehot believed. There are a number of countries that do not rely on any central bank, use foreign currencies as medium of exchange, and seem to do perfectly fine (such as Panama). This seems to show that market practices and relationships with central banks aren’t that entrenched and other models currently do exist, and which could spread relatively quickly.

But what is, in my view, our best hope of getting back to a financial system that follows Hayekian legal principles is Fintech. While Fintech firms have to comply with a number of statute-based laws, they nevertheless remain relatively free (for now) of the all intrusive banking rulebooks and discretionary power of regulators. As such, the multiple IT-enabled Fintech firms and decentralised technologies offer us the best hope of reshaping the financial system in a rule of law-based, spontaneously-emerging, manner. Of course, there will be bumps along the road and some business models will fail and other succeed, but this learning process through trial and error is key in shaping a sustainable system along Hayekian decentralised and experience-based principles. For the sake of our future, let’s refrain from the temptation of legislating and regulating at the first bump.

*At the time of my writing, I have only read the first one, although the second one is next on my reading list

**Although I am not an expert, the evolution of accounting standards over time seems to me to have mostly happened along rule of law principles (although Gordon Kerr, and Kevin Dowd and Martin Hutchinson, would perhaps argue otherwise, which is understandable as IFRS comes from statute-based law systems).

Update: See this follow-up post, which includes some Public Choice theory insights

Photo: Bauman Rare Books

Banking supervision and the rule of law

Since the principles outlined in Locke’s Second Treatise of Government or in Montesquieu’s L’Esprit des Lois, the rule of law has been a major driver of Western advancement. It supports time preference (and hence long-term investments) by ensuring that market actors know what rules are they are subject to and plan accordingly. Discretionary policymaking, on the other hand, tends to raise the sentiment of uncertainty, leading to more risk-averse and short-sighted behaviour.

In Freedom and the Economic System, Hayek suggested that the rule of law was akin to

a system of general rules, equally applicable to all people and intended to be permanent, which provides an institutional framework within which the decisions as to what to do and how to earn a living are left to the individuals.

In The Road to Serfdom, he added that the rule of law meant that

government in all its actions is bound by rules fixed and announced beforehand.

In short, the rule of law is a legal framework that benefits economic development by suppressing the legal uncertainty and arbitrariness of discretionary power.

A new, quite interesting (although most of my readers will find it boring), paper published by NY Fed staff Eisenbach, Haughwout, Hirtle et al, and titled Supervising Large, Complex Financial Institutions: What do Supervisors Do?, describes in details what financial regulators and supervisors do and what actions they take.

What do we learn? (my emphasis)

Prudential supervision involves monitoring and oversight of these firms to assess whether they are in compliance with law and regulation and whether they are engaged in unsafe or unsound practices, as well as ensuring that firms are taking corrective actions to address such practices.

Supervisors send so-called MRIA letters (‘matters requiring immediate attention’) when they identify (my emphasis)

matters of significant importance and urgency that the Federal Reserve requires banking organizations to address immediately and include: (1) matters that have the potential to pose significant risks to the safety and soundness of the banking organization; (2) matters that represent significant noncompliance with applicable laws or regulations; [and] (3) repeat criticisms that have escalated in importance due to insufficient attention or inaction by the banking organization.

Essentially, US supervisors can require bankers to modify their business models, strategy, internal policies and controls, as well as the level of risk-taking they are willing to take, without those requirements being included within any banking regulatory framework signed into federal law. Those decisions are purely at the discretion of supervisors.

It doesn’t take long to figure out that such practices do not follow the principles of the rule of law as outlined above. Supervisors have full discretionary powers to address what they see as weaknesses in banks’ strategy, even if banks disagree.

Firstly, if supervisors’ discretionary demands and measures are indeed so important, why haven’t they been directly included within the (officially signed into law) regulatory framework in the first place?

Second, the traditional critique of any discretionary micromanagement and central planning applies: how can supervisors, many of them having no banking experience, know better than private bankers how to deal with the business of banking? How, with their limited market access, can they know what products customers want and at what price? This is all too reminiscent of Hummel’s depiction of central banking as the new central planning:

In the final analysis, central banking has become the new central planning. Under the old central planning—which performed so poorly in the Soviet Union, Communist China, and other command economies—the government attempted to manage production and the supply of goods and services. Under the new central planning, the Fed attempts to manage the financial system as well as the supply and allocation of credit.

Banking regulation (Dodd-Frank in the US, CRD4 in Europe…) has many, many flaws, as I keep highlighting on this blog. But at least it respects the rule of law to a certain extent. If only banking supervision simply was the practice of ensuring that banks comply with official regulations and not the practice of micromanaging and harmonising private institutions. If only.

Why the Austrian business cycle theory needs an update

I have been thinking about this topic for a little while, even though it might be controversial in some circles. By providing me with a recent paper empirically testing the ABCT, Ben Southwood, from ASI, unconsciously forced my hand.

I really do believe that a lot more work must be done on the ABCT to convince the broader public of its validity. This does not necessarily mean proving it empirically, which is always going to be hard given the lack of appropriate disaggregated data and the difficulty of disentangling other variables.

However, what it does mean is that the theoretical foundations of the ABCT must be complemented. The ABCT is an old theory, originally devised by Mises a century ago and to which Hayek provided a major update around two decades later. The ABCT explains how an ‘unnatural’ expansion of credit (and hence the money supply) by the banking system brings about unsustainable distortions in the intertemporal structure of production by lowering the interest rate below its Wicksellian natural level. As a result, the theory is fully reliant on the mechanics of the banking sector.

The theory is fundamentally sound, but its current narrative describes what would happen in a relatively free market with a relatively free banking system. At the time of Mises and Hayek, the banking system indeed was subject to much lighter regulations than it is now and operated differently: banks’ primary credit channel was commercial loans to corporations. The Mises/Hayek narrative of the ABCT perfectly illustrates what happens to the economy in such circumstances. Following WW2, the channel changed: initiative to encourage home building and ownership resulted in banks’ lending approximately split between retail/mortgage lending and commercial lending. Over time, retail lending developed further to include an increasingly larger share of consumer and credit card loans.

Then came Basel. When Basel 1 banking regulations were passed in 1988, lending channels completely changed (see the chart below, which I have now used several times given its significance). Basel encouraged banks’ real estate lending activities and discouraged banks’ commercial lending ones. This has obvious impacts on the flow of loanable funds and on the interest rate charged to various types of customers.

In the meantime, banking regulations have multiplied, affecting almost all sort of banking activities, sometimes fundamentally altering banks’ behaviour. Yet the ABCT narrative has roughly remained the same. Some economists, such as Garrison, have come up with extra details on the traditional ABCT story. Others, such as Horwitz, have mixed the ABCT with Yeager’s monetary disequilibrium theory (which is rejected by some other Austrian economists).

While those pieces of academic work, which make the ABCT a more comprehensive theory, are welcome, I argue here that this is not enough, and that, if the ABCT is to convince outside of Austrian circles, it also needs more practical, down to Earth-type descriptions. Indeed, what happens to the distortions in the structures of production when lending channels are influenced by regulations? This requires one to get their hands dirty in order to tweak the original narrative of the theory to apply it to temporary conditions. Yet this is necessary.

Take the paper mentioned at the beginning of this post. The authors find “little empirical support for the Austrian business cycle theory.” The paper is interesting but misguided and doesn’t disprove anything. Putting aside its other weaknesses (see a critique at the bottom of this post*), the paper observes changes in prices and industrial production following changes in the differential between the market rate of interest and their estimate of the natural rate. The authors find no statistically significant relationship.

Wait a minute. What did we just describe above? That lending channels had been altered by regulation and political incentives over the past decades. What data does the paper rely on? 1972 to 2011 aggregate data. As a result, the paper applies the wrong ABCT narrative to its dataset. Given that lending to corporations has been depressed since the introduction of Basel, it is evident that widening Wicksellian differentials won’t affect industrial structures of production that much. Since regulation favour a mortgage channel of credit and money creation, this is where they should have looked.

But if they did use the traditional ABCT narrative, it is because no real alternative was available. I have tried to introduce an RWA-based ABCT to account for the effects of regulatory capital regulation on the economy. My approach might be flawed or incomplete, but I think it goes in the right direction. Now that the ABCT benefits from a solid story in a mostly unhampered market, one of the current challenges for Austrian academics is to tweak it to account for temporary regulatory-incentivised banking behaviour, from capital and liquidity regulations to collateral rules. This is dirty work. But imperative.

Major update here: new research seems to confirm much of what I’ve been saying about RWAs and the changing nature of financial intermediation.

* I have already described above the issue with the traditional description of the ABCT in this paper, as well as the dataset used. But there are other mistakes (which also concern the paper they rely on, available here):

– It still uses aggregate prices and production data (albeit more granular): the ABCT talks about malinvestments, not necessarily of overinvestment. The (traditional) ABCT does not imply a general increase in demand across all sectors and products. Meaning some lines of production could see demand surge whereas other could see demand fall. Those movements can offset each other and are not necessarily reflected in the data used by this study.

– It seems to consider that aggregate price increases are a necessary feature of the ABCT. But inflation can be hidden. The ABCT relies on changes in relative prices. Moreover, as the structure of production becomes more productive, price per unit should fall, not increase.

Hummel vs. Haldane: the central bank as central planner

Recent speeches and articles from most central bankers are increasingly leaving a bad aftertaste. Take this latest article by Andrew Haldane, Executive Director at the BoE, published in Central Banking. Haldane describes (not entirely accurately…) the history and evolution of central banking since the 19th century and discusses two possible paths for the next 25 years.

His first scenario is that central banks and regulation will step backward and get back to their former, ‘business as usual’, stance, focusing on targeting inflation and leaving most of the capital allocation work to financial markets. He views this scenario as unlikely. He believes that the central banks will more tightly regulate and intervene in all types of asset markets (my emphasis):

In this world, it would be very difficult for monetary, regulatory and operational policy to beat an orderly retreat. It is likely that regulatory policy would need to be in a constant state of alert for risks emerging in the financial shadows, which could trip up regulators and the financial system. In other words, regulatory fine-tuning could become the rule, not the exception.

In this world, macro-prudential policy to lean against the financial cycle could become more, not less, important over time. With more risk residing on non-bank balance sheets that are marked-to-market, it is possible that cycles in financial assets would be amplified, not dampened, relative to the old world. Their transmission to the wider economy may also be more potent and frequent. The demands on macro-prudential policy, to stabilise these financial fluctuations and hence the macro-economy, could thereby grow.

In this world, central banks’ operational policies would be likely to remain expansive. Non-bank counterparties would grow in importance, not shrink. So too, potentially, would more exotic forms of collateral taken in central banks’ operations. Market-making, in a wider class of financial instruments, could become a more standard part of the central bank toolkit, to mitigate the effects of temporary market illiquidity droughts in the non-bank sector.

In this world, central banks’ words and actions would be unlikely to diminish in importance. Their role in shaping the fortunes of financial markets and financial firms more likely would rise. Central banks’ every word would remain forensically scrutinised. And there would be an accompanying demand for ever-greater amounts of central bank transparency. Central banks would rarely be far from the front pages.

He acknowledged that central banks’ actions have already considerably influenced (distorted?…) financial markets over the past few years, though he views it as a relatively good thing (my emphasis):

With monetary, regulatory and operational policies all working in overdrive, central banks have had plenty of explaining to do. During the crisis, their actions have shaped the behaviour of pretty much every financial market and institution on the planet. So central banks’ words resonate as never previously. Rarely a day passes without a forensic media and market dissection of some central bank comment. […]

Where does this leave central banks today? We are not in Kansas any more. On monetary policy, we have gone from setting short safe rates to shaping rates of return on longer-term and wider classes of assets. On regulation, central banks have gone from spectator to player, with some granted micro-prudential as well as macro-prudential regulatory responsibilities. On operational matters, central banks have gone from market-watcher to market-shaper and market-maker across a broad class of assets and counterparties. On transparency, we have gone from blushing introvert to blooming extrovert. In short, central banks are essentially unrecognisable from a quarter of a century ago.

This makes me feel slightly unconfortable and instantly remind me of the – now classic – 2010 article by Jeff Hummel: Ben Bernanke vs. Milton Friedman: The Federal Reserve’s Emergence as the U.S. Economy’s Central Planner. While I believe there are a few inaccuracies and omissions in Hummel’s description of the financial crisis, his article is really good and his conclusion even more valid today than at the time of his writing:

In the final analysis, central banking has become the new central planning. Under the old central planning—which performed so poorly in the Soviet Union, Communist China, and other command economies—the government attempted to manage production and the supply of goods and services. Under the new central planning, the Fed attempts to manage the financial system as well as the supply and allocation of credit. Contrast present-day attitudes with the Keynesian dark ages of the 1950s and 1960s, when almost no one paid much attention to the Fed, whose activities were fairly limited by today’s standard. […]

As the prolonged and incomplete recovery from the recent recession suggests, however, the Fed’s new central planning, like the old central planning, will ultimately prove an unfortunate and possibly disastrous failure.

The contrast between central bankers’ (including Haldane’s) beliefs of a tightly controlled financial sector to those of Hummel couldn’t be starker.

Where it indeed becomes really worrying is that Hummel was only referring to Bernanke’s decision to allocate credit and liquidity facilities to some particular institutions, as well as to the multiplicity of interest rates and tools implemented within the usual central banking framework. At the time of his writing, macro-prudential policies were not as discussed as they are now. Nevertheless, they considerably amplify the central banks’ central planner role: thanks to them, central bankers can decide to reduce or increase the allocation of loanable funds to one particular sector of the economy to correct what they view as financial imbalances.

Moreover, central banks are also increasingly taking over the role of banking regulator. In the UK, for instance, the two new regulatory agencies (FCA and PRA) are now departments of the Bank of England. Consequently, central banks are in charge of monetary policy (through an increasing number of tools), macro-prudential regulation, micro-prudential regulation, and financial conduct and competition. Absolutely all aspects of banking will be defined and shaped at the central bank level. Central banks can decide to ‘increase’ competition in the banking sector as well as favour or bail-out targeted firms. And it doesn’t stop here. Tighter regulatory oversight is also now being considered for insurance firms, investment managers, various shadow banking entities and… crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending.

Hummel was right: there are strong similarities between today’s financial sector planning and post-WW2 economic planning. It remains to be seen how everything will unravel. Given that history seems to point to exogenous origins of financial imbalances (whereas central bankers, on the other hand, believe in endogenous explanations, motivating their policies), this might not end well… Perhaps this is the only solution though: once the whole financial system is under the tight grip of some supposedly-effective central planner, the blame for the next financial crisis cannot fall on laissez-faire…

New research on finance and Austrian capital theories

Two brand new pieces of academic research have been published last month, directly or indirectly related to the Austrian theory of the business cycle (some readers might already know my RWA-based ABCT: here, here, here and here).

The first one, called Roundaboutness is Not a Mysterious Concept: A Financial Application to Capital Theory (Cachanosky and Lewin) attempts to start merging ABCT (or rather, Austrian capital theory) with corporate finance theory. The authors use the finance concepts of economic value added (EVA), modified duration, Macaulay duration and convexity in order to represent the Austrian concepts of ‘roundaboutness’ and ‘average period of production’. The paper provides a welcome and well-defined corporate finance background to the ABCT.

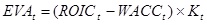

However, finance practitioners still don’t have the option to use a ‘full-Austrian’ alternative financial framework, as this paper still relies on some mainstream concepts. For instance, the EVA calculation for a given period t is as follows:

where ROIC is the return on invested capital, WACC the weighted average cost of capital and K the financial capital invested.

In order to compute the project’s market value added (MVA, i.e. whether or not the project has added value), it is then necessary to discount the expected future EVAs of each period t1, t2…, T, by the WACC of the project:

The WACC represents the minimum return demanded by investors to compensate for the risk of such a project (i.e. the opportunity cost), and is dependent on the interest rate level. The problem arises in the way it is calculated in modern mainstream finance. While the cost of debt capital is relatively straightforward to extract, the cost of equity capital is commonly computed using the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). Unfortunately, the CAPM is based on the Modern Portfolio Theory, itself based on new-classical economics and rational expectations/efficient market hypothesis premises, which are at odds with Austrian approaches.

(And I am not even mentioning some of the very dubious assumptions of the theory, such as “all investors can lend and borrow unlimited amounts at the risk-free rate of interest”…)

While it is easy for researchers to define a cost of equity for a theoretical paper, practitioners do need a method to estimate it from real life data. This is how the CAPM comes in handy, whereas the Austrian approach still has no real alternative to suggest (as far as I know).

Nevertheless, putting the cost of equity problem aside, the authors view the MVA as perfectly adapted to capital theory:

Note that the MVA representation captures the desired characteristics of capital-theory; (1) it is forward looking, (2) it focuses on the length of the EVA cash-flow, and (3) it captures the notion of capital-intensity.

Using the corporate finance framework outlined above, the authors easily show that the more capital intensive investments are the more they are sensitive to variations in interest rates (i.e. they have a larger ‘convexity’). They also show that more ‘roundabout’/longer projects benefit proportionally more from a decline in interest rates than shorter projects. Unsurprisingly, those projects are also the first ones to suffer when interest rates start going up.

The following chart demonstrates the trajectory of the MVA of both long time horizon (high roundabout – HR) and short time horizon (low roundabout – LR) projects as a function of WACC.

Overall, this is a very interesting paper that contains a lot more than what I just described. I wish more research was undertaken on that topic though.

The second paper, pointed by Tyler Cowen, while not directly related to the ABCT, nonetheless has several links to it (I am unsure why Cowen thinks this piece of research actually reflects the ABCT). What’s interesting in this paper is that it seems to confirm the link between credit expansion, financial instability and banks stock prices, as well as the ‘irrationality’ of bank shareholders, who do not demand a higher equity premium when credit expansion occurs (which doesn’t seem to fit the rational expectations framework very well…).

Statism and the ideological war against Bitcoin

While the US Senate provided some support to Bitcoin and other digital alternative ‘currencies’, most of central banks and regulatory authorities around the world seem to have declared war against them. Yesterday, Alan Greenspan, the former Fed Chairman, said that Bitcoin was a bubble and that it had no intrinsic value. Although his track record at spotting bubbles is rather… poor.

China’s central bank, the PBoC, banned financial institutions from doing any kind of business with it. Is it surprising from a country in which citizens are subject to financial repression and capital controls and who as a result see Bitcoin as a step towards financial freedom? It was very unlikely that China would endorse a medium of exchange over which it has no control. This is also true of other central banks. Today, Business Insider reported that the former Dutch central bank president declared that Bitcoin was worse than the 17th century Tulip mania. FT Alphaville continued its recurrent attacks against Bitcoin. The Banque de France also published a very bearish note on the now famous digital currency. The title couldn’t be more explicit: “The dangers related to virtual currencies’ development: the Bitcoin example”. What’s striking with the Banque de France note is that it pretty much sums up all criticisms (misplaced or not) against the virtual currency.

They start with the fact that Bitcoin is “not regulated.” Horror. Well, not only it is the goal guys, but it‘s not even completely true: Bitcoin’s issuance is actually very tightly regulated by its own algorithm, which replaces the discretionary powers of central banks. They add that Bitcoin provides “no guarantee of being paid back” and that its value is volatile. Yes, this is what happens when we invest in any sort of asset. To them, Bitcoin’s limited growth and resulting scarcity was intentionally introduced by its designer to provide it with a speculative nature. Not really… The design was a response to central banks’ lax use of their currency-issuing power. Moreover, Bitcoin’s value is the “exclusive result of supply and demand”! I guess that, for central bankers, this is indeed shocking. For classical liberals like me, or libertarians, this is the way it should be.

I think the ‘best’ argument against Bitcoin is the fact that, as it is anonymous, it can be used in criminal and fraudulent activities and money laundering. Wait… isn’t central bank cash even more anonymous? Hasn’t central bank cash been used in fraudulent activities and money laundering for decades, if not centuries? Are central banks involved in Know Your Customer practices? Finally, another argument of the Bank de France is: there is no authority safeguarding the virtual wallets, exposing them to hackers and other potential threats. True, there is no example in history of ‘authorities’ stealing, debasing or manipulating the reserves of media of exchange they were supposed to ‘safeguard’…* The central bank harshly concludes that Bitcoin’s use “presents no interest to economic agents beyond marketing and advertising, while exposing them to large risks.”

As I have said several times, Bitcoin is surely not perfect. But neither are our current official fiat currencies. I am neither for nor against Bitcoin or any digital currency. I am in favour of letting the markets experiment and pick the currency they judge appropriate. I am against a central authority forcing the use of a certain currency.

Let’s debunk a few other myths.

First, Bitcoin is not money. It is at best a commodity-like asset, such as gold, or a very limited medium of exchange. But it is not a generally accepted medium of exchange, the traditional definition of money. Perhaps someday. But not at the moment. Current institutional frameworks also make it very difficult for it to become generally accepted: legal tender laws, taxation in official currencies, and central banks’ monopoly on the issuance of money severely slow down the process.

As a result, the complaints that we keep hearing that its value is volatile and doesn’t allow for stable prices and economic efficiency through menu costs is completely misplaced. For a simple reason: apart from a few exceptions, there is no price denominated in Bitcoin! When you want to buy a good using Bitcoin, Dollar or Euro (or whatever) prices are converted into Bitcoins. Because Bitcoin has its own FX rate against those various currencies, when its value against another currency fluctuates, the purchasing power of Bitcoin in this currency fluctuates and prices converted into Bitcoins fluctuate! Prices originally denominated in Bitcoin would not fluctuate however.

What happens when you are an American tourist visiting Europe? Your purchasing power is in USD. But you have to buy goods denominated in EUR. As a result, your purchasing power fluctuates every day as you use USD to buy EUR goods. It is the same with Bitcoin. For now Bitcoin effectively involves FX risk. Either the consumer bears the risk of seeing its purchasing power fluctuates, or the seller/producer bears it, knowing that his own input prices were not in Bitcoin. At the moment, in the majority of cases, consumers/buyers bear the risk. Perhaps a bank could step in and start proposing Bitcoin FX derivatives for hedging purposes to its clients? Actually, a Bitcoin trading platform actually already offers an equivalent service.

Something that is really starting to annoy me every time I hear it is that Bitcoin is not like traditional fiat money, as it is not backed by anything and thus has no intrinsic value. Sorry? The very definition of fiat money is that it is not backed by anything! And none of the efforts of some Modern Monetary theorists, chartalists, or FT Alphaville bloggers will manage to convince us of the contrary. They claim that fiat money has intrinsic value as it is backed by “the government’s ability to tax the community which bestows power on it in the first place. This tax base represents the productive capacity of the collective wealth assets of the US community, its land and its resources. The dollar in that sense is backed by the very real wealth and output of the system. It is not just magic paper”, as described by the FT Alphaville blog post mentioned above. Right. This all sounds nice and abstract but can I show up at my local central bank and redeem my note for my share of “the productive capacity of the country”?**

A fiat money isn’t backed by anything at all but by faith. The only thing that gives fiat money its value is economic agents’ trust in it. When this trust disappears the currency collapses. It happened numerous times in history but I guess it is always convenient for some people to forget about those cases. A recent example was the hyperinflation in Zimbabwe: despite legal tenders laws and the fact that taxes were collected in Zimbabwean Dollars, the population lost faith in the currency and turned towards alternatives, mainly USD, EUR and South African Rand. People could well lose faith in advanced economies’ official currencies and start trusting Bitcoin (or any other medium of exchange) more. At that point, Bitcoin would still be fiat but become effectively ‘backed’ by the faith of economic agents and could well trigger a switch in the money we use on a day to day basis.

Another (half) myth is that Bitcoin is only a tool for speculation that diverts real money from real ‘productive purposes’. It is true that, as an asset, Bitcoin will always attract speculators. But it doesn’t necessarily divert money from the real economy: 1. when Bitcoins are sold, they are swapped for real money, money that does not remain idle but then can be used for ‘productive purposes’ by the new holder (or his bank) and 2. as a medium of exchange, Bitcoin can actually facilitate trade and hence ‘productive activities’. Don’t get me wrong: this does not mean that there are no better investment opportunities than Bitcoin. Investors will decide, and if the digital currency is destined to fail, it will, and the markets will learn.

There are other problems with Bitcoin, one of which being that it provides an inelastic currency as its supply is basically fixed. However, in a Bitcoin-standard world (as opposed to a gold-standard), we could probably see the emergence of fractional reserve banks that would lend Bitcoin substitutes and issue various liabilities (notes and deposits mainly) denominated in Bitcoin and redeemable in actual Bitcoin (which would then play the role of high-powered money). This mechanism would then provide some elasticity to the currency (and therefore to the money supply) to respond to increases and decreases in the demand for money.

Bitcoin seems to enrage central bankers, regulators, Keynesians (particularly post-Keynesians), chartalists, Modern Monetary theorists and other statists. Consequently they resort to myths and misconceptions in order to threaten its credibility. As I have already said, my stance is neutral. Alternative currencies will come and go. Some will fail. Others will succeed. Markets will decide. I argue that alternative currencies contribute to the greater good as they all of a sudden introduce monetary competition between emerging private actors and traditional centralised institutions. If alternative currencies can eventually force central banks and states to better manage their own currencies, it would be for the benefit of everyone.

To end this piece, let me quote Hayek:

But why should we not let people choose freely what money they want to use? By ‘people’ I mean the individuals who ought to have the right whether they want to buy or sell for francs, pounds, dollars, D-marks or ounces of gold. I have no objection to governments issuing money, but I believe their claim to a monopoly, or their power to limit the kinds of money in which contracts may be concluded within their territory, or to determine the rates at which monies can be exchanged, to be wholly harmful.

Well said mate.

* This was irony, for those who didn’t get it.

** The spontaneous development of alternative local currencies (such as this one) by individuals lacking balances in the official currency of the country but willing to trade goods or to propose services, is another example of a non-state issued money (and not collected to pay taxes) that facilitate economic output and the generation of wealth, in direct contradiction to the state theory exposed above.

Chart: CNN

Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – A graphical experiment

Today is going to be experimental and theoretical. I have already outlined the principles behind the RWA-based variation of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), which was followed by a quick clarification. I am now attempting to come up with a graphical representation to illustrate its mechanism. In order to do that, I am going to use Roger Garrison’s capital structure-based macroeconomics representations used in his book Time and Money: The Macroeconomics of Capital Structure. I am not saying that what I am about to describe is 100% right. Remember that this remains an experiment that I just wrote down over those last few days and that needs a lot more development. There may well also be other ways of depicting the impacts that Basel regulation’s RWAs have on the capital structure and malinvestments. Completely different analytical frameworks might also do. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

This is what Garrison’s representation of the macroeconomics of capital structure looks like:

It is composed of three elements:

- Bottom right: this is the traditional market for loanable funds, where the supply and demand for loanable funds cross at the natural rate of interest. It represents economic agents’ intertemporal preferences: the higher they value future goods over present goods, the more they save and the lower the interest rate. The x-axis represents the quantity of savings supplied (and investments) and the y-axis represents the interest rate.

- Top right: this is the production-possibility frontier (PPF). In Garrison’s chart, it represents the sustainable trade-off between consumption and gross investment. Only movements along the frontier are sustainable and supposed to reflect economic agents’ preferences. Positive net investments and technological shocks expand the frontier as the economy becomes more productive.

- Top left: this is the Hayekian triangle. It represents the various stages of production (each adding to output) within an industry. See details below:

I don’t have time to come back to the original ABCT and those willing to find out more about it can find plenty of examples online. Today I wish only to try to understand the impact of regulatory-defined risk-weighted assets on this structure. Ironically, it becomes necessary to disaggregate the Austrian capital-based framework to understand the mechanics and distortions leading to a likely banking crisis. In everything that follows, and unlike in the original Austrian theory, we exclude central banks from the picture (i.e. no monetary injection). We instead focus only on monetary redistribution. The story outlined below does not explain the financial crisis by itself. Rather, it outlines a regulatory mechanism that exacerbated the crisis.

I don’t have time to come back to the original ABCT and those willing to find out more about it can find plenty of examples online. Today I wish only to try to understand the impact of regulatory-defined risk-weighted assets on this structure. Ironically, it becomes necessary to disaggregate the Austrian capital-based framework to understand the mechanics and distortions leading to a likely banking crisis. In everything that follows, and unlike in the original Austrian theory, we exclude central banks from the picture (i.e. no monetary injection). We instead focus only on monetary redistribution. The story outlined below does not explain the financial crisis by itself. Rather, it outlines a regulatory mechanism that exacerbated the crisis.

Let’s take a simple example that I have already used earlier. Only two types of lending exist: SME lending and mortgage/real estate lending. Basel regulations force banks to use more capital when lending to SME and as a result, bankers are incentivised to maximise ROE through artificially increasing mortgage lending and artificially restricting SME lending, as described in my first post on the topic.

In equilibrium and in a completely free-market world with no positive net investment, the economy looks like Garrison’s chart above. However, bankers don’t charge the Wicksellian natural rate of interest to all customers: they add a risk premium to the natural rate (effectively a ‘risk-free’ rate) to reflect the risk inherent to each asset class and customer. Those various rates of interest do reflect an equilibrium (‘natural’) state, which factors in the free markets’ perception of risk. Because lending to SME is riskier than mortgage lending, we end up with:

natural (risk free) rate < mortgage rate (natural rate + mortgage risk premium) < SME rate (natural rate + SME risk premium)

What RWAs do is to impose a certain perception of risk for accounting purposes, distorting the normal channelling of loanable funds and therefore each asset class’ respective ‘natural’ rate of interest. Unfortunately, depicting all demand and supply curves, their respective interest rates and the changes when Basel-defined RWAs are applied would be extremely messy in a single chart. We’re going to illustrate each asset class separately with their respective demand and supply curve. Let’s start with mortgage (real estate) lending:

Given the incentives they have to channel lending towards capital-optimising asset classes, bankers artificially increase the supply of loanable funds to all real estate activities, pushing the rate of interest below the natural rate of the sector. As the actual total supply of loanable funds does not change, returns on savings remain the same. In our PPF, this pushes resources towards real estate. Any other industry would interpret the lowered rate of interest as a shift in people’s intertemporal preferences towards the future and increase long-term investments at the expense of short-term production. Indeed, long-term housing projects are started. This is represented by the thin dotted red triangle.

Given the incentives they have to channel lending towards capital-optimising asset classes, bankers artificially increase the supply of loanable funds to all real estate activities, pushing the rate of interest below the natural rate of the sector. As the actual total supply of loanable funds does not change, returns on savings remain the same. In our PPF, this pushes resources towards real estate. Any other industry would interpret the lowered rate of interest as a shift in people’s intertemporal preferences towards the future and increase long-term investments at the expense of short-term production. Indeed, long-term housing projects are started. This is represented by the thin dotted red triangle.

However, the short-term housing supply is inelastic and cannot be reduced. The resulting real estate structure of production is the plain red triangle. Nonetheless, real estate developers have been tricked by the reduced interest rate and the long-term housing projects they started do not match economic agents’ future demand. Meanwhile, savers, adequately rewarded for their savings, do not draw down on them (or don’t have to), but are instead incentivised to leverage as they (indirectly) see profit opportunities from the differential between the natural and the artificially reduced rate. Leverage effectively becomes a function of the interest rate differential:

The increased leverage boosts the demand for existing real estate, bidding up prices, starting a self-reinforcing trend based on expected further price increases. We end up in a temporary situation of both short-term ‘overconsumption’ of real estate and its associated goods, and long-term overinvestments (malinvestments). This situation is depicted by the thick dotted red triangle and represents an unsustainable state beyond the PPF.

On the other hand, bankers artificially restrict the supply of loanable funds to SME, pushing the rate of interest above the natural rate. Tricked by a higher rate of interest, SMEs are led to believe that consumers now value more highly present goods over future goods (as they ‘apparently’ now save less of their income). They temporarily reduce interest rate-sensitive long-term investments to increase the production of late stages consumer goods. This results in an overproduction of consumer goods relative to economic agents’ underlying present demand. Nonetheless, wealth effects from the real estate boom temporarily boost consumption, maintaining prices level. Overconsumption of present goods could also eventually appear if and when savers start leveraging their consumption through low-rate mortgages, as house prices seem to keep increasing. In the long-run, SMEs’ investments aren’t sufficient to satisfy economic agents’ future demand of consumer goods.

With leverage increasing and the economy producing beyond its PPF, the situation is unsustainable. As increasingly more people pile in real estate, demand for real estate loanable funds increases, pushing up the interest rate of the sector. Interest payments – which had taken an increasingly large share of disposable income in line with growing leverage – rise, putting pressure on households’ finances. The economy reaches a Minsky moment and real estate prices start coming down. Real estate developers, who had launched long-term housing projects tricked by the low rates, find out that these are malinvestments that either cannot find buyers or are lacking the financial resources to be completed. Bankruptcies increase among over-leveraged households and companies. Banks start experiencing losses, contract lending and money supply as a result, whereas savers’ demand for money increases. The economy is in monetary disequilibrium. Welcome to the financial crisis designed in the Swiss city of Basel.

This all remains very theoretical and I’ll try to dig up some empirical evidences in another post. Nonetheless, the story seems to match relatively well what happened in some countries during the crisis. Soon after Basel regulations were implemented, household leverage in Spain or Ireland took off and came along with increasing house prices and retail sales, which both collapsed once the crisis struck. Under this framework, the artificially restricted supply of loanable funds to SME and the consequent reduction in long-term investments could also partly explain the rich world manufacturing problems. However, I presented a very simple template. As I mentioned in a previous post, securitisation and other banking regulations (liquidity…) blur the whole picture, and central banks can remain the primary channel through which interest rates are distorted.

RWA-based ABCT Series:

- Banks’ risk-weighted assets as a source of malinvestments, booms and busts

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Update

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – A graphical experiment

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Some recent empirical evidence

- A new regulatory-driven housing bubble?

Recent Comments