150 years of nominal interest rates distortion?

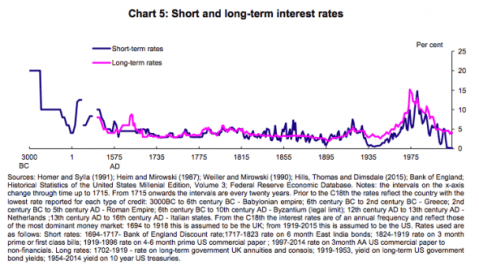

A very useful post was published on the FT Alphaville blog by David Keohane. It shows nominal interest rates levels over the past 5000 years in three different charts.

The first one comes from Andy Haldane, from the BoE:

The second one from Hartnett, from Bank of America Merrill Lynch:

The last one comes from Costa Vayenas, from UBS:

Those charts use different sources so don’t look exactly the same. Nevertheless, they all show the same striking facts. In particular, the 20th and 21st centuries seem to have been huge monetary experiments: nominal rates went both sky high and negative within a few decades… Within a period of barely more than a 100 years, rates fell to the bottom (Great Depression), then jumped ridiculously high to counteract inflationary pressure in the 1970s and 1980s (i.e. the disastrous impact of crude Keynesian macro theory) that resulted from the money multiplier recovering after the Depression, then fell to the bottom again or even negative (Great Recession).

Remember: the 20th century was the period of the generalisation of central banking. It definitely looks like they have been successful at stabilising money markets (and remember this paper by Selgin and White, which shows how successful the Fed has been at stabilising the value of the dollar since its creation). In short, great success for central bankers*.

Another interesting fact is that nominal rates started to wildly fluctuate once the BoE was granted the exclusive right to issue banknotes in the London area in 1844. Unlikely to be a coincidence.

Something that worries me though is the current state of monetary policy throughout most of the Western world. Rates are stuck at the zero bound or even went negative for the first time in history. Perhaps this is justified. But I keep wondering whether our economies currently are in a worse state than at any time in history to justify such low rates (although to be fair, Haldane’s chart does show that long-term nominal rates remain around historical levels – but not Hartnett’s).

Real interest rate charts would also have been interesting for a more comprehensive analysis of the underlying drivers of the rate movements we see here. If ever anyone has access to real interest rate data that go back several hundred years, please let me know (probably hard, or even impossible, to obtain as historical inflation data is likely to be non-existent).

In a parallel world, the BoE recently opened a forum weirdly titled ‘Building real markets for the good of the people’ which, putting aside the slightly communist tone of its chosen name, describes markets are “prone to excess” if “left unattended”**. This is another great example of central banks succeeding in making public opinion believe that economic issues originate, not in central bankers’ failed policies, not in economically distortive banking regulation, but in free markets. Which aren’t actually free. Here again Selgin had a remarkable article reporting how the Fed promotes itself.

One reaches some sort of supreme irony after contrasting those BoE statements with the charts above. Worse, central banks’ power, despite the instability they have brought to the economy for 100+ years, is growing, and their adherence to the rule of law has all but vanished (see Salter here and here arguing that a stable monetary framework such as the gold standard or NGDP targeting would respect the rule of law, unlike current regimes, and that adherence to the rule of law should be the primary consideration for judging monetary regimes).

*Sarcasm, of course

**I’m not sure what’s going on at the BoE, but a culture shift seems to be happening: anti-market rhetoric and rather strange monetary and banking theories are overtaking the institution (see my posts on endogenous money theory)

Blockchain everywhere

Banks are both scared and overexcited. Blockchain has the potential to fundamentally alter their business model, and they know it. Understanding tomorrow’s financial tech has become key to minimise business risks, key to remain relevant. A race that all financiers have joined is now going on, despite mocking Bitcoin just a couple of year ago. And blockchain is all over the news, despite most bankers having little to no understanding of what it is about. Financiers of all sorts now back blockchain-based technologies, from credit card companies to stock exchange and banks.

So a few weeks ago the NYT ironically remarked that:

Nowhere are more money and resources being spent on the technology than on Wall Street — the very industry that Bitcoin was created to circumvent.

Bloomberg reports that Blythe Masters, former MD at JPMorgan who helped kick start the credit default swap market, was now CEO of a blockchain startup, Digital Asset Holdings. Probably not what Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s legendary creator, was expecting indeed. She says that, as I have explained on this blog, banks could massively benefit from blockchain technology if it can simplify back office operations. That is, if banks aren’t completely disintermediated first.

Matt Levin reflects on Masters’ comments and wonders why it is taking so long for the financial sector to eventually implement systems that drastically cut error-prone settlement delays (that can still be longer than 20 days, in the internet era…), and says that blockchain for banks can’t hurt. It’s certainly true, although don’t expect miracles: it’s going to take a few attempts, and perhaps a few failures or even mini-crises, for a blockchain-based system to evolve into something solid. And if it turns out that blockchain cannot offer a lasting, bulletproof solution, it will disappear.

Masters also declared that US banks were rather slow at looking at potential blockchain solutions. And indeed, most banks that seemed very active in that area, at least that I have heard of so far, were not US-based. Many of them were European, perhaps reflecting the fact that they currently are under more profitability pressure than their US peers. UBS, for instance, has been very vocal about its blockchain initiatives. See also this quite complex article on IBTimes on the various technologies behind UBS’ ideas, which include private blockchains, sidechains (transfer of assets between multiple blockchains) and ‘settlement coins’ (essentially a fiat money representation on blockchain that relies on central banks’ settlement processes):

Recently, UBS demonstrated how a bond could be automated on a blockchain, the shared ledger system similar in design to that used by Bitcoin. It also proposed a fiat currency-backed “settlement coin” to fit within the existing regulatory framework. The bank appears to be leading the way in distributed ledger technology at this time.

What’s happening is fascinating. What’s going to finally emerge remains a mystery. While individual institutions can put in place private blockchain-type systems to cut costs or offer more effective dark pool services to a selection of customers, the implementation of a ‘stock-market replacement’ blockchain requires an industry-wide agreement. And it does seem to be happening. A couple of days ago, the FT reported that 9 of the largest banks agreed to cooperate on a blockchain initiative that would define common standards and protocols (I’d just like to add that this is another example of private market actors cooperation; no need for a state to devise that sort of things in most, if not all, cases).

But blockchain technologies don’t only apply to financial services. The NYT mentioned property titles, diamond and gold ownership, airline miles. But also the music industry. And certainly a lot of other ones, as some at the MIT seem to believe with their Enigma project, or some entrepreneurs I met a few months ago at a conference, who believed that entire applications such as Facebook could be transferred onto the blockchain. It’s now ‘blockchain everywhere’.

PS: I’m on holidays abroad so have little time for updates!

Bank accounting standards can worsen recessions

There is a row over the new IFRS 9 standards. Those are new accounting rules supposed to be introduced by 2018 (outside of the US). As this FT article summarises:

Banks were unable to book accounting losses until they were incurred, even though they could see the losses coming. At times the incurred loss rule meant banks overstated profits upfront and did not make prudent provisions against expected losses, particularly in areas such as loans secured against property.

Now, as I said a few weeks ago, accounting rules seem to mostly respect the rule of law as described by Hayek, by experimenting, learning from their mistakes and evolving, step by step. The process can be slow and the experiment can turn wrong in the short run. Whether IFRS standards have respected this process is arguable.

A FT editorial declares that banks should not be able to game the rules, whatever that means. Hence it welcomes the changes. Not everyone agrees. But the FT column is contradictory. It complains that banks were “slow to react to emerging problems when the financial crisis struck” and that “they allowed outright concealment of economic realities” by shifting some assets from fair valued portfolios (i.e. marked to market) to held-to-maturity ones (i.e. reported at amortised cost). This may be right, but I’m not sure.

First, is this really ‘gaming the rules’? No, it is simply applying the rules. Second, I’ve always doubted that mark-to-market accounting really reflected the ‘fair value’ of an asset. It reflects its market price at a given time. Which isn’t the same thing. Markets panic, in particular during financial crises. This tends to temporarily amplify fluctuations in market prices. Volatility increases widely. By holding assets at fair value, you can be bankrupt on Monday and solvent on Friday. When markets have lost all notion of a fair, or equilibrium, price, it is silly to speak about banks’ assets being ‘fair valued’. This can only happen once markets have calmed down and prices only fluctuate marginally around a certain level.

Friedman and Kraus, in their great book Engineering the Financial Crisis, describe how AIG could have survived if it, counterparties and US regulators had waited a few months so that the market price of a number of its trades recovered. It could have then potentially avoided a bail-out. I don’t know the circumstances of Lehman Brothers in detail, but it is certain that its insolvency was partly triggered by short-term price fluctuations that forced short-term asset write-downs.

In fact, mark-to-market accounting can amplify recessions by making banks’ balance sheets look much worse than they really are. The result of which is that banks drastically reduce lending and lay off staff, aggravating the collapse in aggregate demand beyond what would have happened had those accounting rules not been in place. For instance, a lot of structured financial products lost half or more of their market value during the crash, but only a tiny portion actually defaulted! (see here and here) Is it worth penalising financial institutions and, in fine, the economy, for temporary changes in prices? Beware what you wish for.

Apparently, even Milton Friedman blamed mark-to-market accounting for many bank failures during the Great Depression (I don’t have an original source though; perhaps in the Monetary History of the United States, but I can’t recall).

Let’s get back to our provisioning methods. The ‘incurred loss’ model wasn’t perfect: banks under IFRS were not free to provision the amount they wanted when they wanted, the goal being to prevent bankers from ‘managing’ their profits. While this can be a laudable goal, this is also risky: as with the conflict between marked-to-market and amortised cost accounting rules described above, ‘managing’ profits can dampen economic booms and busts, at the expense of short-term financial statement reliability.

Under the new ‘expected loss’ model, banks will have to provision upfront on all loans, although only over the following 12-month period according to my understanding. It still doesn’t give banks much flexibility and only changes the timing of the provisioning. A loan becomes costlier at origination, but not over its lifetime. But as often, the comments on the two FT articles are more interesting than the article itself. And some worry that those new standards have pro-cyclical features, by statistically requiring higher level of provisioning at origination during recessions, thereby mechanically requiring more capital. Which of course would be likely to impair banks’ lending appetite when they already struggle to make decent returns on their existing capital base.

Perhaps the less economically distorting way would be to go back to pre-WW2 loan loss provisioning standards: there were apparently none. It is now well-known that 19th century and early-20th century banks used to hold a lot thicker capital buffers.

While there are many reasons why equity buffers fell (better institutional framework, better access to information, more diversified business models…), accounting standards are another reason: they progressively created loan loss reserve accounts from WW2 onwards, originally for tax reasons (see Walter here). Loan loss reserves’ purpose was to provide a buffer for expected losses, whereas equity mostly became a buffer for unexpected losses. Before that, equity was an all-purpose buffer and loans were not provisioned but directly ‘charged-off’. In the US, only 38% of banks had loan loss reserve accounts in 1948. By 1975, 94% of them did.

So to be fair with banks, the chart above should add provisioning (which is a ‘negative’ asset) to equity. A back of the envelope calculation I made some time ago seemed to show that equity/asset levels would rise by 100/300bp. Still below late 19th century levels, but not as bad as many believe. By letting bankers decide the amount of the buffer (reserves or equity) and the timing of its increase/decrease, some banks would inevitably fail, but it is also likely that, on aggregate, stability could be enhanced as pro-cyclicality is reduced.

I am not saying here that there should not be any accounting rules in place. Those would be necessary to provide investors with relatively accurate information (and there have been discussions and proposals to radically change provisioning methods. See Kerr here). But too much rigidity leading to very accurate statements at a point in time that would then be completely undermined a few months later as a crisis strikes and losses are revealed, is of limited use. And economically damaging. There might be other middle way options that I am missing, but available choices seem to me to be: point-in-time accurate and long-term inaccurate or point-in-time inaccurate and long-term accurate.

PS: See also this interesting BIS paper that reviews the literature on the relationship between accounting rules, regulation and business cycles. It takes a different view on fair value accounting and says that there is no real conclusive evidence that fire sales occurred and damaged banks’ balance sheet as a result. Maybe, but fire sales by banks don’t have to occur to make mark to market losses on assets. It also finds some pro-cyclicality due to provisioning rules, but research is preliminary and sometimes contradictory.

Cash is a vital barbarous relic

The FT recently published a column calling for the retirement of cash, this ‘barbarous relic’ (a reference to Keynes on the gold standard in his Tract on Monetary Reform). The author takes the view that, because “by far the largest amount of money exists and is transacted in electronic form”, cash has become almost irrelevant. Worse, the little amount of cash circulating in society could “cause a lot of distortion to the economic system” and “limits central banks’ ability to stimulate a depressed economy” because people could convert their deposits into cash if the central bank decides to apply negative interest rates far below zero on deposits. And, worst of all, cash is anonymous:

The second feature of cash is that, unlike electronic money, it cannot be tracked. That means cash favours anonymous and often illicit activity; its abolition would make life easier for a government set on squeezing the informal economy out of existence.

The whole article is filled with economic fallacies and what quite a few commenters called ‘fascist’ and ‘authoritarian’ measures. While I wouldn’t go as far as qualifying such views as ‘fascist’ they are surely ‘authoritarian’, and it is frightening to see that some people (including some leading economists) are willing to give up a part of their freedom to allow central authorities (either the state or a supposedly independent central bank) to monitor and control the activities of all their citizens. Here again, as usual with interventionists of all sorts, any notion of Public Choice has been forgotten: governments seem to be well-meaning, omniscient and omnipotent organisations, which would also become omnipresent if such measures were adopted. This would give governments free rein to oppress people in a subtle way or another, whether bureaucrats were right or wrong.

One commenter, in a superb reference to Star Trek (and to the concept of separation of Church and state), summed up my view with the statement that (his emphasis)

The world needs separation of money and state, not a melting consolidation of the double helix into the Borg.

A response letter to this column is also reassuring:

The state can more easily levy a value added tax in order to make tax collection easy. How nice! Here — let me put my cash in the bank in order to make it easier for government to tax it away. Then you conclude your support of the cashless society with the caveat that we minions might, just might, be allowed to carry some cash . . . but at a cost. Our cash could carry an expiration date, for example.

As you state: “The benefits of cash are significant — but they need not be offered for free.” A more Orwellian statement would be hard to find.

But, besides the threat to liberty that a suppression of cash represents, I wish to offer here another economic reason why banning cash is a bad idea.

Cash is a control system on the banking industry. Cash, which represents banks’ reserves and most liquid assets, has been the main control tool that has kept bankers in check for centuries. The threat of deposit (i.e. claims on cash) outflow prevents banks from overexpanding, mostly through the adverse interbank clearing (mostly for individual banks) or outright withdrawal (for the system as a whole, see what happened in Greece, the most extreme version of this being a bank run) mechanisms. This is a pure market discipline effect. The fact that, in normal times, most financial transactions are done electronically is irrelevant. It is because people still have the last resort option to withdraw their deposit that makes cash such a potent control tool.

Of course, some banks are mismanaged and become illiquid from time to time. Liquidity risk is one of the main risks faced by banks and is carefully monitored, despite what some endogenous money theorists, who claim that reserves would always be supplied in case of need (while forgetting the demand side of the equation), seem to imply.

There is one option though: physical cash could be retired, as long as electronic cash could be withdrawn and stored outside of the banking system. This is the Bitcoin-solution: people can keep their Bitcoins in encrypted electronic wallets on their phones or computers, which are not accessible by outsiders (unlike bank deposits).

Retiring cash outright would however unlock a crucial financial stability mechanism, which was already weakened by the introduction of deposit insurance. Several studies have indeed controversially found that deposit insurance, which tends to reduce the pace of deposit outflow, has a detrimental effect on bank stability (see Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache here, Calomiris here, Chu here), despite what Diamond and Dybvig claimed in their famous (but flawed) model in 1983. Far from improving financial stability and allowing central banks to ‘manage the economy’ (as if this was actually possible), the suppression of cash would be a step closer to the ultimate moral hazard.

PS: I’m also curious as to what the impact of the suppression of cash on charity would be (or for tips at restaurants and elsewhere for instance). What would you reply to the question “can you spare a coin”? “What’s your bank account number?”?

Photo: Newport webpage

Natural interest rates are dead, the BIS (indirectly) says

In May (I only found out a couple of weeks ago), the BIS released a big report titled Regulatory change and monetary policy, in which it investigates the effects of the new banking regulatory framework on market interest rates and the implied consequences for the conduct of monetary policy. By the BIS’ own admission, the whole yield curve has nothing ‘natural’ left.

The report is an interesting, though pretty technical read. It is also scary. Scary to see how much banking regulation is affecting interest rates all along the yield curve across most banking products. Scary to see that the suggested remediation by the BIS is more central bank involvement to counteract the effects of those regulations.

Of course, the Basel framework originates from… Basel in Switzerland, where the BIS is located, and where BIS experts have spent years drafting apparently clever rules to make our banking system apparently safer, in spite of all historical evidences and what we’ve learned about the spontaneous order of free markets (remember: “banking is different” they say). So I wasn’t expecting this BIS report to declare that the very rules it put in place was endangering the economy. And indeed it doesn’t. But it does admit that there will be ‘impacts’, which of course will be ‘limited’ and ‘manageable’. They always are.

I won’t replicate here everything that’s in that report. It’s way too long and I’ll let you take a look at it if you’re interested. There is a quite detailed description of the potential effects of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, the Net Stable Funding Ratio, the Leverage Ratio and the Large Exposure Limits on banks’ product pricing and volume and the impact on central bank’s monetary policy operations. And despite its 30+ pages, the report isn’t even comprehensive. It forgets to look at the large distortive effects of risk-weighted assets and credit conversation factors.

What I’m going to show you below is merely the BIS researchers’ own conclusions, which they neatly summarised in handy tables. This is what they view as the potential changes in money market interest rates:

By their own admission, the cumulative effect of those new rules is unclear. And even when they believe they know which way the interest rate will move, it remains a best guess. To this table you can add the hugely distortive effects of RWAs and CCFs, which I have described on this blog a number of times.

The only conclusion is that there is no free market-defined Wicksellian ‘natural’ interest rate anymore in the marketplace. As interest rates are manipulated by regulatory measures in myriads of ways, entire yield curves across the whole spectrum of banking products and asset classes stop reflecting the pricings that market actors would normally agree on in an unhampered market. The result is a large shift in the structure of relative prices in the economy.

The economic consequences are likely to be damaging (and it is clear, at least to me, that RWAs have already done a lot of damages, i.e. the financial crisis), even though the BIS reckons that central banks could potentially offset some of those interest rates movements:

More central bank intermediation: Many of the new regulations will increase the tendency of banks to take recourse to the central bank as an intermediary in financial markets – a trend that the central bank can either accommodate or resist. Weakened incentives for arbitrage and greater difficulty of forecasting the level of reserve balances, for example, may lead central banks to decide to interact with a wider set of counterparties or in a wider set of markets.

In addition, in a number of instances, the regulations treat transactions with the central bank more favourably than those with private counterparties. For example, Liquidity Coverage Ratio rollover rates on a maturing loan from a central bank, depending on the collateral provided, can be much higher than those for loans from private counterparties.

Problem is (and the BIS also admits it): there is no way non-omniscient central bankers know by how much and in what direction rates should be offset. We here get back again to the knowledge problem. There is no way the central bank can act in a timely manner. It is also unlikely that central bankers could act free from any political interference. Finally, even if central banks managed to figure out what the ‘natural’ rate is for a given asset at a given maturity, central banks’ policies are likely to have unintended consequences by altering the rates of other products and maturities.

The effectiveness of the transmission mechanism (banking channel) of monetary policy is more than ever questioned. Rates will move in unexpected ways. And, as the BIS describes, banks could simply opt out of monetary programmes altogether:

The question is whether there are exceptional situations in which banks would refrain from subscribing to fund-supplying operations because concerns over the LR impact of the reserves that would be added to the banking system in aggregate outweigh the financial benefits accrued by participating in the operations. If so, this lack of participation could prevent a central bank whose operating framework entailed increasing the quantity of reserves from meeting its operating target.

The BIS believes that “the changing regulatory environment will, by design, affect banks’ relative demand across various types of assets and liabilities”. It summarises the potential changes in the demand for central bank tools below:

Here again, a lot of uncertainties remain.

Something looks certain however. The involvement of central banks in the financial and economic system is likely to become more intense. As regulations bound banks’ behaviour and prevent an effective allocation of capital, central banks are increasingly going to step in to boost or restrict the supply of credit to certain market actors and asset classes. See what happened with SMEs, starved of credit as Basel makes it too expensive to extend credit to such customers, while central banks attempted to offset this effect by starting specific lending programmes (such as the Funding for Lending scheme in the UK). We are here again back to Jeff Hummel’s arguments of the central bank as central planner.

Nonetheless, I am certain that capitalism and free markets will get blamed for the next round of crisis. It is becoming urgent that we replicate the achievement of academics such as Friedman and Hayek, who managed to overturn the nonsense post-War Keynesian consensus. Sadly, free markets academics seem to have virtually disappeared nowadays or at least cut off from most policymaking positions and public debate.

Financial knowledge dispersion and banking regulation

I have never hidden my admiration for Hayek’s work, in particular over the last few weeks. The name of this blog is itself derived from Hayek’s concept of spontaneous order. I view Mises as having laid the foundations of a lot of Hayek’s and modern Public Choice theory thinking (see Buchanan’s admission that Mises “had come closer to saying what I was trying to say than anybody else”). He was to me a more comprehensive theorist than Hayek, and made us understand through his methodological individualism method that human action was at the heart of economic behaviour. But Hayek’s brilliant contribution is to have built on Mises’ business cycle, market process and entrepreneurship insights to develop a coherent and deep philosophical, legal, political and economic paradigm. While some would argue that he didn’t push his logic far enough (see here or here), it remains that reading the whole body of Hayek’s work is truly fascinating and enlightening. It suddenly feels like everything is connected and that “it now all makes sense”.

Some of Hayek’s insights are verified on a day-to-day basis. He repeatedly emphasised that knowledge was dispersed throughout the economy and that no central authority could ever be aware of all the ‘particular circumstances of time and place’ in real time. This knowledge problem was core to his spontaneous order theory, which describes how market actors set up plans independently of each other according to their needs and coordinated through the price system and respect for the ‘meta-legal’ rules (what he later called ‘rules of just conduct’) of the rule of law.

I have very recently offered a critique of macro-prudential regulation based on Hayek’s and Public Choice’s insights. But his description of the knowledge problem also applies. Zach Fox, on SNL (link gated), reports that the whole of macro-prudential regulatory framework may be useless because the US agency in charge of tracking the data can only access outdated, if not completely wrong, datasets. This agency calculates ‘systemic risk’ scores from a number of data points sent by various banks. Problem: those figures keep being revised by many banks, sometimes radically, leading to large fluctuations in ‘systemic risk’ scores and regulators keep using outdated data:

SNL has only been able to track the movements by scraping each bank’s individual filing periodically over the last year. U.S. banks filed their 2013 systemic risk reports by July 2014, at which point SNL reported on the data. After noticing some differences, SNL followed up Jan. 13, 2015. In total, 12 data points had changed across the filings for eight different banks. Then, in July 2015, SNL noticed yet more revisions to the 2013 filings.

Fox concludes:

When a bank’s derivative exposure shrinks by $314 billion — roughly half the size of Lehman when it filed bankruptcy — it raises questions about the company’s ability to model accurately in real-time. When that change does not come until 16 months after the initial filing, it raises questions about the Fed’s vigilance. And when the government’s office established to track systemic risk uses incorrect, outdated data, it raises questions about the entire theory of macroprudential supervision.

(one could add: “and of micro-prudential supervision”)

In short, due to dispersed nature of financial knowledge (i.e. data) across the whole banking sector and the inherently bureaucratic nature of the data collection and analysis process, regulatory agencies do not have ability to collect accurate data in a timely manner, and hence act when really necessary.

Of course, some banks also seem to struggle to report the required data. But they are much closer to their own ‘particular circumstances of time and place’ and hence can take action way before the data even reach the regulator. Moreover, banks are organisations that comprise several layers of individuals, each of them facing their own particular circumstances. Knowledge is dispersed among bankers who deal with clients on a daily basis and goes up the hierarchical chain if and when necessary. Governmental agencies are at the very end of this chain and informed last, way after the actions have taken place (or the disaster occurred).

Of course, this does not mean that commercial banks are always effective in dealing with data and that all their decisions are taken rationally. But a central regulatory agency would not have the ability to make the bank safer either. Forcing banks to adopt certain standards in advance could help solve the problem to an extent only, as circumstances vary and standards may not be appropriate for all situations or could even exacerbate problems as I keep emphasising on this blog (and are likely to be a harmful and unnecessary drag on economic performance).

PS: The Chinese central bank is about to cut reserve requirements to boost lending according to the WSJ. Clearly China hasn’t been infected by the MMT/endogenous money virus yet.

PPS: Kinda related to this post, but definitely related to this blog, see this Hayek’s quote of the day:

Above all, however, I am bound to stress that in the course of the work on this book I have been, by the confluence of political and economic considerations, led to the firm conviction that a free economic system will never again work satisfactorily and we shall never remove its most serious defects or stop the steady growth of government, unless the monopoly of the issue of money is taken from government. I have found it necessary to develop this argument in a separate book, indeed I fear now that all the safeguards against oppression and other abuses of governmental power which the restructuring of government on the lines suggested in this volume are intended to achieve, would be of little help unless at the same time the control of government over the supply of money is removed. Since I am convinced that there are now no longer any rigid rules possible which would secure a supply of money by government by which at the same time the legitimate demands for money are satisfied and the value of that money kept stable, there appears to me to exist no other way of achieving this than to replace the present national moneys by competing different moneys offered by private enterprise, from which the public would be free to choose which serves best for their transactions.

It comes from the chapter 18 of Law, Legislation and Liberty (which I have now read), and highlights a significant evolution in Hayek’s thinking since The Constitution of Liberty, in which he had argued in favour of government managing the money supply (but should do it well of course).

Leveraged housing bubbles are the most damaging ones

Jordà and his colleagues are quickly becoming some of my favourite economic researchers. Not because we necessarily share the same fundamental economic believes (probably not, at least to my knowledge) but because they keep publishing remarkable pieces of financial data gathering.

In their most recent publication, titled Leveraged Bubbles, they reached a conclusion that could sound relatively obvious to most people versed in Austrian or Minskyite business cycle theories, namely that

what makes some bubbles more dangerous than others is credit. When fueled by credit booms asset price bubbles increase financial crisis risks; upon collapse they tend to be followed by deeper recessions and slower recoveries. Credit-financed house price bubbles have emerged as a particularly dangerous phenomenon.

But, as usual, it’s their dataset that’s the most interesting, and on which further empirical research can be based. They provide a dataset of bank credit, real estate and stock prices across 17 different countries, starting around 1870.

What do they find? That combined housing and equity bubbles leading to financial recession are a characteristic of the post-WW2 world:

Whereas equity price booms play a prominent role in those financial recessions associated with a bubble episode before WW2 (8 out of 12 bubble related financial crisis recessions involve equities alone), after WW2 it appears that most episodes involved bubbles in both equity and house prices—11 out of 21 episodes are linked to bubbles in both asset classes.

And that, this is necessarily linked to the huge mortgage lending growth of the era:

Building on the original data collected by Schularick and Taylor (2012), Jorda, Schularick and Taylor (2014) break-down bank lending into mortgage and non-mortgage lending. While both types of bank lending experienced rapid growth in the post-WW2 era, the share of mortgages relative to other types of lending grew from a low point of less than 20% in the 1920s to the nearly 60% in the Great Recession.

As I have pointed out in a review of their previous research publications, this isn’t surprising at all given that the whole Basel regulatory framework has made it much easier (and more rational) for banks to maximise their lending allocation to the real estate sector. In short, Basel has institutionalised the debt-fuelled housing bubble.

And this made the whole economy more vulnerable. They point out that housing bubbles are

considerably more damaging events. The drag on the economy is nearly twice as big when accompanied by higher than average credit growth. In terms of the path of the recession and recovery, we note that it can sink the economy for several years running so that even by year 5 the economy is still operating below the level at the start of the recession.

In other words (not theirs, but mine), Basel, by attempting to make the financial system safer, has made it (and the whole economy) weaker (and it would actually be better to live in a stock bubble-prone world). And the impact on economic growth is dramatic:

Given that housing prices have been strongly increasing again in many countries since the onset of the crisis, there is nothing reassuring in their results.

The Hayek quote I came across last week is more relevant than ever. Micromanagement of the banking system is bound to disappoint its supporters.

A few things I read elsewhere

Just a quick few points today.

Scott Sumner has a few posts on whether or not growth is inflationary. He says:

If NGDP growth rose by 4%, and both RGDP growth and inflation rose by 2%, it would look like growth was inflationary. But in fact the NGDP growth (i.e. monetary policy) was causing 4% higher inflation, ceteris paribus, and the extra 2% RGDP growth was holding down the inflation rate, limiting the increase in inflation to 2%.

If this is the way the world works then one might expect many cognitive illusions to form. People would think growth was inflationary, whereas in fact it would be deflationary, as the regression in the previous post showed, and as our theoretical model predicts. Procyclical inflation would reflect bad monetary policy (unstable NGDP growth) and inflation would be strongly countercyclical under a sound monetary policy regime (stable NGDP growth.) If the central bank predicts that inflation will pick up during a boom period, they are predicting their own incompetence.

THIS.

I have grown tired over the past few years of economists, analysts and journalists predicting that inflation would be back because RGDP growth was coming back.

I missed another very confusing post by Izabella Kaminska (referring to a blog post by Peter Stella) a few days ago about ‘hyper liquidity’. To make it short, I agree about the term ‘hyper liquid’, but the rest of the post seems to be way off the mark. I say ‘seems’, because I’m really unsure I understand what the h*ll she’s trying to say.

Can someone translate this for me please:

As Stella notes, this is why the common conception that banks lend reserves “out” to non-banks is simply nonsense. Reserves are not for lending. At best they’re part of a penalty system, representing the amount of value/capital that needs to be withheld to protect the system from bad agents. It’s a cover. Insurance.

Indeed, re-lending reserves would defy the point of holding reserves in the first place.

What banks actually lend out is credit.

Credit represents a guarantee that the bearer of a bank’s coupons (who has been vetted) will not squander the assets/goods provided to him, but work to replace them in a meaningful value-adding way which grows the system as a whole rather than contracts it.

That doesn’t mean funding isn’t important! It is hugely important. We simply mustn’t confuse funding for something it isn’t. When a bank’s credit is well funded (so, the new assets it creates through lending), this means the current coupons (liabilities) it issues to the borrower for use in the real economy are guaranteed to square with what the system has available for sale within that timeframe. The funding represents a “store of anything to be drawn upon.” Funding can and is relent. But it’s what a bank doesn’t lend out, but keeps in its own reserve at an opportunity cost to itself, which counts as a bank capital reserve. It’s pre-funding.

When banks issue unfunded liabilities, there is no guarantee that the system is able to service them. Thus, there may be inflationary consequences.

The whole thing doesn’t make any sense to me, from an accounting or an economic point of view. Apparently, funding can be relent, but what is not relent is a capital reserve, which is pre-funding. Wait… what? I really don’t get it. Perhaps I just need holidays.

The assumption in the post that the bank reserve system is ‘closed’ is simply wrong. Reserves leak all the time, at least through deposit withdrawal (you don’t withdraw credit at the ATM. You withdraw high-powered money, deducted from the bank’s reserve account at the central bank). Stella (and possibly Kaminska) also seems to forget that it can take many decades for the money multiplier to recover. Banks don’t really lend out reserves: they extend credit on top of those reserves. Hence the money multiplier. And this funding/pre-funding/re-funding/asset funding/capital funding/ultra funding/turbo funding story is just crazy.

Finally, in light of my fights against Basel’s RWAs, I stumbled upon the following very relevant quote from F.A. Hayek:

The contention often advanced that certain political measures were inevitable has a curious double aspect. With regards to developments that are approved by those who employ this argument, it is readily accepted and used in justification of the actions. But when developments take an undesirable turn, the suggestion that this is not the effect of circumstances beyond our control, but the necessary consequence of our earlier decisions, is rejected with scorn.

This perfectly fits the RWAs example. Well-meaning regulators came up with a system that would reduce the accumulation of risk in our banking system. Events didn’t turn the way they expected, but it wasn’t the fault of the original rules of course (even if they massively favoured real estate lending over corporate lending). But don’t worry citizen: they are working on making those rules even better. See the result on this brand new chart from the WSJ:

We already knew that all residential property markets were cooling down all around the world. Now it looks like the CRE market is also calming down. The new rules are indeed working. Good job folks!*

*I hope you got the irony

Macro-pru, regulation, rule of law and public choice theory

Another rule of law-related post. It might be the anniversary of the Magna Carta that brought this topic back in fashion. Consider it as a follow-up post to my Hayekian legal principles post of a couple of weeks ago.

John Cochrane has a very long post on the rule of law on his blog (which could have been an academic article as the pdf version is 18-page long) titled The Rule of Law in the Regulatory State.

His vision is a little gloomy, but spot on I believe:

This rule of law always has been in danger. But today, the danger is not the tyranny of kings, which motivated the Magna Carta. It is not the tyranny of the majority, which motivated the bill of rights. The threat to freedom and rule of law today comes from the regulatory state. The power of the regulatory state has grown tremendously, and without many of the checks and balances of actual law. We can await ever greater expansion of its political misuse, or we recognize the danger ahead of time and build those checks and balances now.

He believes the rise of the regulatory state does not fit the standard definitions of socialism, regulatory capture or crony capitalism. He believes that we are

headed for an economic system in which many industries have a handful of large, cartelized businesses— think 6 big banks, 5 big health insurance companies, 4 big energy companies, and so on. Sure, they are protected from competition. But the price of protection is that the businesses support the regulator and administration politically, and does their bidding. If the government wants them to hire, or build factory in unprofitable place, they do it. The benefit of cooperation is a good living and a quiet life. The cost of stepping out of line is personal and business ruin, meted out frequently. That’s neither capture nor cronyism.

He thinks the term ‘bureaucratic tyranny’ could be appropriate to describe the situation, and that it is the ‘greatest danger’ to our political freedom. That is, opposing or speaking out against a regulatory agency, a politician or a bureaucrat might prevent you from obtaining the required regulatory approval to run your business.

He takes what seems to be a Public Choice view when he states that “the regulatory state is an ideal tool for the entrenchment of political power was surely not missed by its architects.”

While his post covers all sorts of industries, and while his definition of the rule of law (and its difference with mere legality) isn’t as comprehensive as Hayek’s, it remains pretty interesting. He actually has a lot to say on the current state of banking and financial regulation:

The result [of Dodd-Frank] is immense discretion, both by accident and by design. There is no way one can just read the regulations and know which activities are allowed. Each big bank now has dozens to hundreds of regulators permanently embedded at that bank. The regulators must give their ok on every major decision of the banks.

While he says that, for now, Fed staff involved in bank stress tests are mostly honest people, he is wondering how long it will take before the Fed (pushed by politicians or not) stop resisting the temptation to punish particular banks by designing stress tests (whose methodology is undisclosed) to exploit their weaknesses.

While Cochrane laments the rise of discretionary ruling and its consequences on freedom, The Economist also just published a warning, albeit a less-than-passionate one. Since the crisis, The Economist has always taken a somewhat ambivalent, if not completely contradictory double-stance (for instance, it takes position against rules in monetary policy in the same weekly issue). Here again, the newspaper believes that the crisis made new rules ‘inevitable’, because taxpayers ‘need protection from the risks of failure’. And that, as a result, regulators needed ‘flexible’ rules (MC Klein made a similar point some time ago – see my rebuttal here).

By and large, The Economist has approved that sort of rulemaking, as well as the use of macro-prudential policies (something I have regularly criticised on this blog). Nevertheless, the newspaper also complains about abuse of discretionary decision-making and the effect of regulatory regime uncertainty (a term originally coined by Robert Higgs). It doesn’t seem to have realised that the nature of what it was requesting (i.e. respect of the rule of law and control of the industry and of the monetary system by regulatory agencies) was by nature antithetical. Cochrane’s fears (as well as mine) thus seem justified if such a classical liberal newspaper cannot even realise this simple fact.

Public Choice theory could be used as a strong rebuttal to the regulatory discretion rationale. As Salter points out in a remarkable paper titled The Imprudence of Macroprudential Policy, the economic and political science behind discretionary macro-pru policies taken by bureaucratic agencies suffers from major flaws that regulators or academics haven’t even tried to address.

He highlights the fact that, as Mises and Hayek had already mentioned decades ago during the socialist calculation debate, regulatory agencies lack the information signalling system to figure out what the ‘right’ market price should be and hence act in the dark, possibly making the situation even worse* (and empirical evidences do show that it doesn’t work), and that the assumption of the macro-pru literature that capitalist (and financial) systems are inherently unstable is at best unproven. A typical example is Basel’s capital requirements: as I have long argued on this blog, RWAs incentivise the allocation of credit towards asset classes that regulators deem safe. The fact that they are aware of the allocative power that they have is clearly illustrated by the recent news that EU regulators would lower capital requirements on asset-backed securities to persuade insurance firms to invest in them! Yet they continue to blame banks for over-lending for real estate purposes and not enough ‘to the real economy’. Go figure.

Worse, Salter continues, macro-pru regulation (and his critique also applies to all other regulatory agencies) assumes away all Public Choice-related issues, taking for granted omniscient regulators always acting in the ‘public interest’. Yet proponents of strong regulatory agencies seem to ignore (voluntarily or not – rather voluntarily if we believe Cochrane) that regulatory agencies themselves can fall prey to the private interests of regulators, whether those are power, money, job… If not directly to the regulators, regulatory agencies can fall prey to voters’ irrationality, as Caplan would argue (but also Mises and Bastiat), leading elected politicians to put in place regulators executing the irrational wishes of the voters. The resulting naïve line of thought of the macro-pru and regulatory oversight school is dangerous and goes against the body of knowledge that Western civilization has accumulated since the Enlightenment period.

And such occurrences are not only present in the minds of Public Choice theorists. They are happening now. The case of the head of the British Financial Conduct Authority directly comes to mind: whether or not one agreed with his “shoot first, ask questions later” method (and many didn’t), he was removed from office by the new UK government as he didn’t fit in the new political ‘strategy’.

What can we do? Cochrane proposes a Magna Carta for the regulatory state, in order to introduce the checks and balances that are currently lacking in our system (for instance, appeals are often made with the same regulatory agency that took the decision in the first place). Buchanan would certainly argue for a similar constitutional solution that would attempt a return to the ‘meta-legal’ principles of the rule of law described by Hayek, with an independent judiciary as the main arbitrator.

The wider public certainly isn’t ready to accept such changes given its negative opinion of particular industries (they’d rather see more regulatory oversight). Consequently, the only way to convince them that constitutional constraints on regulatory agencies are necessary seems to me to remind them that regulatory discretion negatively affects them as well (and day-to-day examples of incomprehensible regulatory decisions abound). If broad principles can be agreed upon from the day-to-day experience of millions of people, they should apply more broadly to all types of sectors. As Salter concludes for macro-prudential policies (although it applies to any regulatory agency):

Market stability is ultimately to be found in institutions, not interventions. Institutions that are robust to information and incentive imperfections must be at the heart of the search for stable and well-functioning markets. Robust monetary institutions themselves depend on adherence to the rule of law and the protection of private property rights, which are the cornerstone of any well-functioning market order. Since macroprudential policy relies on unjustifiably heroic assumptions concerning the information and incentives facing private and public agents, its solutions are fragile by construction.

*Cowen and Tabarrok take another angle here by arguing that the problem of ‘asymmetric information’, which underlies most regulatory thinking, almost no longer exists in the information/internet age.

Cryptosolutions and cryptolimitations

Over the past few weeks I’ve read quite a few articles and papers on Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. Some positive, some negative, some providing useful insights as to how finance can evolve in the future. Here is a little summary that illustrates rather well the concept of ‘spontaneous order’ in financial services.

On Coin Center, Juan Llanos argues that Bitcoin and the blockchain could revolutionise financial regulation, by providing real-time accounting information, which would replace than the current invasive, after-the-fact, often paper-based, regulatory oversight. Forget about the ‘information asymmetry’ nonsense (in my view) of the article. But he really has a point: transparency and processing speed and effectiveness would be considerably enhanced. There are limitations to this process however: the valuation of a number of financial instruments (what is often called ‘Level 2’ and ‘Level 3’ fair valued assets in the jargon) remains quite subjective. It remains to be seen how any automated blockchain or IT-based system can solve this subjectivity problem.

On Coin Center again, Chris Smith explains how Bitcoin addresses micropayments, which are regularly subject to transaction fees in store. Bitcoin radically reduces the fee, but does not eliminate it. According to him, Bitcoin offers an alternative solution: micropayment channels. They are “a cryptocurrency specific technology that allows for the aggregation of many small transactions into a single transaction, turning many fees into a single fee.” He goes on to explain the underlying technology and provides examples. Interesting read.

In City AM, Jerry Norton says that the blockchain will help you buy your house. He explains that the blockchain transforms the traditional ‘Delivery versus Payment’ protocol, which could particularly come in handy in the case of real estate transactions:

Today, when you’re buying a house you need to do so within working hours and with your solicitor acting as a mechanism for DVP. When the buyer transfers the money to the seller’s solicitor, his or her own solicitor receives the deeds. This process of ‘exchange and completion’ can take several weeks, and only happens during business hours, usually involving a CHAPS payment made in a branch.

With the blockchain concept of a smart contract, the exchange of the deeds and the funds transfer could be proven, linked together automatically, whilst happening in near real time and theoretically on a 24/7 basis.. The same principles are true for many asset types and purchases, such as buying a second-hand car – a process fraught with risk today.

On Alt-M, Larry White believes that cryptocurrencies don’t need regulation but more competition because innovators “need freedom to discover and pursue the most beneficial technologies.” He also thinks that, in a free society, there is no evidence that people prefer a currency that produces a stable price level and, consequently, Bitcoin could well become widely adopted.

On Coindesk, Stan Higgins reports a survey on blockchain technologies conducted by Greenwich Associates (Blomberg also does here). It is clear that bankers are currently reviewing options to implement blockchain-based solutions. However, Bitcoin itself seems to be of little interest. I unfortunately don’t have access to the report, but it seems full of interesting charts such as this one:

It is clear that blockchain-based technologies have multiple financial applications. I’m a little confused about ‘counterparty risk’ though, which seems to me to rely more on qualitative assessment than on automation and transaction recordings. But I might be missing something.

In the latest Cato journal, Larry White published a paper called The Market for Cryptocurrencies. Interesting paper, in particular the description of the cryptocurrency market and the various alternatives to Bitcoins (and their tech differences). He also repeats what he declared about regulatory intervention in the Alt-M interview above:

The market for cryptocurrencies is still evolving, and (to most economists) is full of surprises. Policymakers should therefore be very humble about the prospects for improving economic welfare by restricting the market. Israel Kirzner’s (1985) warning about the perils of regulation strongly applies here: Interventions that block or divert the path of entrepreneurial discovery will prevent the realization of potential breakthroughs such that we will never know what we are missing.

In the same journal, Kevin Dowd and Martin Hutchinson published a rather negative, but very interesting, view of Bitcoin titled Bitcoin Will Bite the Dust, in which they list of the ‘defects’ (at least in their view) of Bitcoin. In particular, they focus on the flaws of the mining system, which they view as leading to natural monopolies leaving the door open for 51% attacks. They however declare that other cryptocurrencies could be technically more elaborated and secure. They conclude:

we should remember that a recurring theme in the history of innovation is that the pioneers rarely, if ever, survive. This is because early models are always flawed and later entrants are able to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors. There is no reason why Bitcoin should be an exception to this historical rule.

Recent Comments