The BoE’s FLS delusion

The Bank of England reported yesterday the latest statistics of one of its flagship measures, the Funding for Lending Scheme. Unsurprisingly, they are disappointing. No, more than that actually: the FLS has been pretty much useless.

When launched mid-2012, the FLS was supposed to offer cheap funding to British banks in exchange for increased business and mortgage lending (though originally, authorities strongly emphasised SMEs in their PR as you can imagine) in order to ‘stimulate the economy’. The only effect of the scheme was to boost… mortgage lending.

The BoE, unhappy, decided to refocus the scheme on businesses (including SMEs) only, in November last year. Well, as I predicted, it was evidently a great success: in Q114, net lending to businesses was –GBP2.7bn and net lending to SMEs was –GBP700m. Since the inception of the scheme, business lending has pretty much constantly fallen (see chart below).

According to the FT:

Figures from the British Bankers’ Association showed net lending to companies fell by £2.3bn in April to £275bn, the biggest monthly decline since last July.

The BoE argues that we don’t know what would have happened without the scheme. Perhaps lending would have fallen even more? That’s a poor argument for a scheme that was supposed to boost lending, not merely reduce its fall. Not even all large UK banks participated in the scheme (HSBC and Santander didn’t). Moreover, some banks withdrew only modest amounts because they could already access cheaper financial markets by issuing covered bonds and other secured funding instruments, or, if they couldn’t, used the FLS to pay off existing wholesale funding rather than increase lending… The FLS funding that did end up being used to lend was effective in boosting… the mortgage lending supply.

The UK government has also ‘urged’ banks to extend more credit to SMEs. Still, nothing is happening and nobody seems to understand why. For sure, low demand for credit plays a role as businesses rebuild their balance sheet following the pre-crisis binge. Still, nobody seems to understand the role played by current regulatory measures. Central bankers are supposed to understand the banking system. The fact that they seem so oblivious to such concepts is worrying.

On the one hand, you have politicians, regulators and central bankers trying to push bankers to lend to SMEs, which often represent relatively high credit risk. On the other hand, the same politicians, regulators and central bankers are asking the banks to… derisk their business model and increase their capitalisation. You can’t be more contradictory.

The problem is: regulation reflects the derisking point of view. Basel rules require banks to increase their capital buffer relatively to the riskiness of their loan book; riskiness measures (= risk-weighted assets) which are also derived from criteria defined by Basel (and ‘validated’ by local regulators when banks are on an IRB basis, i.e. use their own internal models).

Those criteria require banks to hold much more capital against SME exposures than against mortgage ones. Banks that focus on SMEs end up squeezed: risk-adjusted SME lending return is not enough to generate the RoE that covers the cost of capital on a thicker equity base. Banks’ best option is to reduce interest income but reduce proportionally more their capital base to generate higher RoEs. Apart from lending to sovereigns and sovereign-linked entities, the main way they can currently do that is to lend… secured on retail properties…

(I have already described here how this process creates misallocation of capital and possibly business cycles)

As such, it is unsurprising that mortgage lending never turned negative in the UK (even a single month) throughout the crisis. Even credit card exposures haven’t been cut by banks, as their risk-adjusted returns were more beneficial for their RoE than SMEs’. Furthermore, alternative lenders, who are not subject to those capital requirements, actually see demand for credit by SMEs increase (see also here).

Let’s get back to the 29th of November 2013. At that time, after it was announced that the FLS would be modified, I declared:

RWAs are still in place! Mortgage and household lending will still attract most of lending volume as it is more profitable from a capital point of view.

Well…

As long as those Basel rules, which have been at the root of most real estate cycles around the world since the 1980s, aren’t changed, SMEs are in for a hard time. And economic growth too in turn. Secular stagnation they said?

PS: this topic could easily be linked to my previous one on intragroup funding and regulators “killing banking for nothing”. Speaking of the ‘death of banking’, Izabella Kaminska managed to launch a new series on this very subject without ever saying a word about regulation, which is the single largest driver behind financial innovations and reshaped business models. I sincerely applaud the feat.

PPS: The FT reported how far regulators (here the FCA) are willing to go to reshape banking according to their ideal: equity research in the UK is in for a pretty hard time. This is silly. Let investors decide which researchers they wish to remunerate. Oversight of the financial sector is transforming into paternalism, if not outright regulatory threats and uncertainty.

PPS: I wish to thank Lars Christensen who mentioned my blog yesterday and had some very nice comments about it.

The importance of intragroup funding – 19th century Canada

This is a quick follow-up post on intragroup funding, as promised in the one focusing on the US experience during the 19th century.

The Canadian case is interesting, because Canada is also a ‘recent’ country that experienced its own banking development at the same time as its close, also ‘recent’, neighbour, the US. Though the contrast cannot be starker; while the US was prone to recurrent financial crises during the 19th century, Canada’s financial system remained pretty stable throughout the period, and continued to do so until today.

The main difference between the Canadian and the US banking systems was their fragmentation and regulation. The US, as described earlier, had a very fragmented and highly regulated (though much less than today…) banking system, whereas Canada had a lightly regulated and quite concentrated one (some could argue that it was pretty much an oligopoly). In the US, a multitude of unit banks with no branches and local monopolies prevailed. In Canada, large nationwide banks with multitude of branches prevailed. This was due to the specific political and institutional arrangements in Canada: unlike in the US, where states had most of the powers to charter banks, the Canadian government was the one who decided whether or not to grant a bank charter, not the provinces. In 1890, there were 38 chartered banks in Canada and around 8000 in the US.

It is easy to understand why the Canadian banking system was more stable: nationwide branch network allowed banks to move liquidity around and continue to accept each others’ notes at par, and loan books were much more diversified and less prone to local asset quality deterioration. When branches in the West of the country were experiencing a liquidity shortage, it was easy to provide them with extra liquidity from their cousin in the East in order to avoid contagion as banks tried to protect their name and reputation. Moreover, the fact that only a few banks had large market shares in the country made it a lot easier to coordinate a response in times of financial tension, pretty much like the US clearinghouse system, but on a much larger scale.

The consequences of this design were that banks operated on thinner liquidity and capital buffers than banks in the US, as credit and liquidity risks could be consolidated and diversified away. Furthermore, credit was as available in Canada as in the US and deposit rates were higher, while banks were nonetheless more profitable thanks to centralised back office functions on a nationwide basis (i.e. economies of scale).

In the end, Canada experienced not a single bank failure during the Great Depression, despite having no central bank nor deposit insurance, the two tenets of current banking regulatory ‘good practices’.

What is striking from my series of posts on intragroup funding is that history is crystal clear: it is large, diversified, banking groups that represent a more stable ideal than insulated, but reinforced, smaller local banks. Unfortunately, most regulators and economists don’t seem to know much banking history…

The importance of intragroup funding – 19th century US vs. modern Germany

I recently explained the importance of intragroup liquidity and capital flows to prevent or help solve financial crises and why new regulations are weakening banks, and showed the inherent weakness in the design of the 19th century US banking system. Today I wish to highlight the similarities, and more importantly, the differences, between the 19th century US banking system and the modern German banking system.

As previously described, the peculiar US banking system had a multitude of tiny unit banks that were not allowed to branch, with very little financial flows and support behind them (at least until they started setting up local clearinghouses). By 1880, there were about 3,500 banks in the US, meaning about 1 bank for 14,000 people. Nowadays, there are about 1,800 banks in Germany, meaning one bank for 45,000 people. Germany’s banking system isn’t as fragmented as the 19th century US one, but it is still very fragmented by developed economies’ standards.

By comparison, in the UK, there is one bank for 410,000 people, though most banks have no retail banking market share, meaning this figure is probably way overestimated (my guess is that there is actually one bank for about 3m people). In Germany though, most banks have a retail banking market share: the banking system is divided between the large private banks (which actually don’t account for much of the local retail market share and focus mostly on corporate lending and investment banking), the cooperative banks group (the Volksbanken and Raiffeisenbanken, representing around 1,200 small retail banks), and the savings banks group, the largest banking group in Germany (the Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe, representing slightly less than 450 retail banks).

Those Sparkassen, for instance, cannot compete with each other and cannot branch out of their local area, making both their loan books and funding structures highly undiversified, with restrictions very similar to those that applied to 19th century US banks. Moreover, many of those banks have relatively small capital and liquidity buffers, at least compared to the US banks. Nevertheless, the Sparkassen have demonstrated remarkable resilience over time, experiencing very few failures (all have been bailed out). How to explain this?

First, all Sparkassen depend on local Landesbanks, which, quite similarly to clearinghouses in 19th century US, play the role of local central banks, moving liquidity around according to the needs of their Sparkassen members. This process alleviates acute liquidity crises. But this isn’t enough to avert regional crises or national, systemic ones.

Second, the Sparkassen rely on another mechanism: several regional and interregional support funds that allow healthy banks to recapitalise or provide liquidity to endangered sister Sparkassen. Those support funds can be complemented by extra contributions from healthy Sparkassen if ever needed. This mechanism is akin to some sort of intragroup funds flows*.

Here we go: instead of insulating each bank, raising barriers to allegedly make them more resilient, the Sparkassen allow funds to circulate when needed. They understand that the actual failure of one of their members would have catastrophic ramifications for the rest of the group (and for their shared credit rating). It is in their best interest to mutually support each other. But guess what? Some Sparkassen now fear that European regulators will take action to make such intragroup mutual support flows illegal…

* The Volksbanken have a relatively similar structure and intragroup support mechanism, though there are differences. Both groups are also actively involved in intragroup peer monitoring, which is important to limit moral hazard.

The importance of intragroup funding – The 19th century US experience

This is a follow-up post to my previous one on banks’ intragroup funding.

Financial and banking historians have known for a long time what the BoE believes it has ‘discovered’. A prime example of the importance of being able to move funds around (whether under the form of capital or liquidity) is the experience of US banking in the 19th century.

In the 19th century, the US was plagued by recurrent banking crises. This was mostly due to strict limitations on the development and growth of banks that basically isolated banks from each other. The result was known as ‘unit banking’. I am not going to enter into all the details (and this post mainly refers to the North of the US) but I strongly advise you to check the references at the bottom of this post.

The US’ political arrangements made it very difficult for the federal government to charter banks on a national basis, as the experiments of the First and the Second Banks of the United States demonstrate. States, on the other hand, could charter banks of issue within their borders to help finance the states’ expenditures. They also tended to forbid interstate branching in order not to leak out sources of funds to other states and artificially limit competition within their borders, as banking monopoly rents led to more abundant funding resources for the states (taxes could account for close to a quarter or even a third of total state financing). Many large cities ended up having a single bank at the very beginning of the 19th century.

The race for financing led states to charter increasingly more banks. However, new laws divided states into districts and allowed only a very limited number of banks to be chartered within each of them. Banks also did not have the right to open branches throughout the states. In the end, the whole banking system was completely fragmented in a myriad of small banks that enjoyed local monopolies.

From the 1830s, ‘free banks’ started to appear, a trend that accelerated following the 1837 banking crisis during which many banks failed throughout the country. This prompted a movement to increase competition in banking and access to credit for those who could not access the traditional, restricted, banking system. Free banks could be opened without any approval by state regulators. They still came to the funding need of state governments as the free banking laws required the full-backing of banknotes with high-quality securities, mostly government debt. Crucially, free banks were not allowed to branch. The previous system of larger banks that were constrained in their growth by their inability to open branch in other states, or simply in other districts, was progressively replaced by a system of a multitude of tiny ‘unit’ banks. In the end, the number of banks massively grew but unit banks often retained local monopolies. The federal government eventually tried to find ways to increase the number of nationally-chartered banks, but in the end those banks faced the same legal constraints that prevented free banks to branch.

There was political power behind those unit banks: because they couldn’t expand, unit banks were incentivised to lend to their local community even when times were tough (if they didn’t, they wouldn’t make any money and would fail anyway…). Banks were numerous (there were more than 27,000 banks in the US early-20th century, 95% of which had no branches…) but geographically isolated. As a result, they suffered from high levels of concentration in their loan books and deposit base, and were particularly badly hit by local economic problems. Liquidity risk was high and banks could hardly get hold of extra funds to face bank runs when they occurred.

Some banks tried to organise themselves into holding companies, owning several unit banks. However, the law prevented any financial or operational integration between various banks. The only thing they ended up sharing was a common ownership structure. A partial solution came up with the setup of clearinghouses, which basically settled interbank transactions, but also played the role of coordinator during local crises.

As a result of this poorly-designed banking structure, financial crises were recurrent: there were 11 of them between 1800 and 1914. Post-clearinghouses crises were nonetheless milder as clearinghouses allowed some liquidity to circulate.

Where does this lead us?

I described in my previous post how intragroup funding allows banking systems to remain more stable by allowing liquidity to circulate from stronger entities to weaker ones (this also applies to capital).

The 19th century US is an extreme example of what happens when you prevent this free movement of funds: a few banks fail and indirect contagion weakens even the stronger banks, leading to a systemic collapse. When banking groups are larger and free to move funds around, on the other hand, they have an incentive to reinforce their weaker links. Think about those 19th century ‘bank holdings’, which could not operationally integrate their various unit banks: the collapse of one of their ‘unit bank subsidiaries’ could potentially endanger the existence of all unit banks owned by that holding company through economic and financial contagion. Wouldn’t it be simpler to allow the transfer of funds from one unit bank to another to prevent any failure in the first place and actually reassure depositors that their banks are solid?

Unfortunately, current regulations aims at fragmenting and isolating national banking systems (and types of banks). This is likely to transform our globalised banking system into a mild version of what happened in the US, rather than into the stronger and more resilient systems that regulators hope to build. In the US, each unit bank had to maintain relatively high levels of capital and liquidity given their inherent weakness and lack of diversification. Was it enough to prevent crises? Not at all. This is in contrast with the Canadian experience, whose banking system comprised a few, very large, lightly regulated, branching banks. The Canadian banking system remained very stable throughout the period (and later).

More on 19th century Canada in a subsequent post.

Recommended readings:

- Charles A. Conant, A History of Modern Banks of Issue

- Charles Calomiris and Stephen Haber, Fragile by Design

- Christopher Whalen, Inflated: How Money and Debt Built the American Dream

- Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States

Update: I added one very important and great book to the list…

Is regulation killing banking… for nothing? The importance of intragroup funding

Last week, Barclays, the large UK-based bank, announced massive job cuts and asset reductions in its investment banking division which effectively signal the end of its ambition to compete with Tier 1 US banks. One of the main causes of that withdrawal is clear: regulations now make it a lot more costly to sustain capital market activities as Basel 3 has increased market risk capital requirements. But also, UK-specific rules, which advocate a ring-fencing of retail activities, also played a role in disadvantaging British banks. By ring-fencing retail banks from their sister investment ones, banks have to set up separate funding structures and look for separate funding sources, which makes it more expensive to fund investment banking divisions. Some would say that this is a good thing, as investment banking is “risky and caused the crisis”. This is wrong. In the UK and most of the world, it is mostly retail banks that failed as their asset quality strongly declined following the lending boom*.

This clampdown on investment banking is unfortunate, but wouldn’t undermine the whole banking system by itself. Regrettably, all aspects of banking are now being revisited and harmonised to please ‘out of control’ (in the words of one of my friends) regulators. Often though, the measures they take actually make banks weaker.

A brand new study published last month by the Bank of England itself (does the BoE read its own reports?) highlighted this very contradiction (see summarised post on Vox). What did it find?

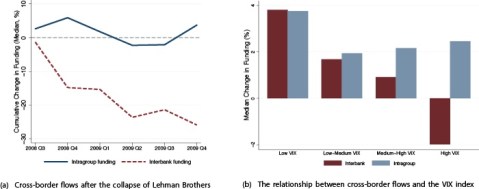

The left-hand side panel of Figure 3 shows that interbank funding fell on average across our sample of BIS reporters by almost 30% between September 2008 and the end of 2009. Yet, in contrast, intragroup funding increased in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of Lehman Brothers and was stable for the remainder of the crisis period.

The contrasting behaviour of interbank and intragroup flows is not limited, however, to the recent global financial crisis. To see this, in the right-hand side panel of Figure 3, we present the distributional relationship across time between cross-border bank-to-bank funding and the VIX index.

We find that on average, between 1998 and 2011, interbank funding contracted by 2% during quarters when the VIX index was at an elevated level (upper-25th percentile), while during the same quarters intragroup funding expanded by over 2%. In the quarters when the VIX index was particularly low (lower-25th percentile), both intragroup and interbank funding expanded by approximately 4%.

This is self-explanatory. Globalisation of banking led to increased stability of funding flows. Local subsidiaries with excess liquidity were able to transfer some reserves to sister subsidiaries in other countries (or within the same country) and parent banks were also able to retrieve some of those excess funds in case they were under pressure at home. Banking system whose interbank funding comprises high share of intragroup experienced much lower drop in funding during the crisis**.

But, wait a minute… What’s the current regulatory logic? In the UK, the goal of ring-fencing is clear: ‘insulation’ (see the UK Commission report on banking reform). Globally, Basel 3 regulations now require each subsidiary of international banking groups to hold high levels of liquid assets and comply with a Net Stable Funding Ratio. By itself, this means that subsidiaries have a limited power to transfer liquidity intragroup even if they don’t need it at a given moment. Only liquidity/funding in excess of those (already high) limits could be transferred. In theory, local regulators can decide to supersede the original Basel framework. In practice, regulators are often reluctant to allow cross-border intragroup support, as they narrowly focus on their own national banking system and actually raise extra barriers, including capital controls. This happened during the crisis and potentially made it worse. This is what a BIS survey reported:

Respondents indicated that in some jurisdictions a banking parent can easily and almost without limit support its subsidiaries provided the parent continues to meet its liquidity standards. However, banking subsidiaries face legal lending limits on the amount of liquidity they can upstream to their parent even when they have excess liquidity.

Certain respondents claimed that these legal lending limits are inefficient when managing the liquidity and funding position of a banking group overall and advised that they expect future banking regulation to further institutionalise these inefficiencies. As such, in their view, subsidiaries will need a liquidity buffer for their own positions that the greater group is not able to use.

Furthermore, since the survey, financial nationalism has increased. As Bloomberg reported in February:

The Federal Reserve approved new standards for foreign banks that will require the biggest to hold more capital in the U.S., joining other countries in erecting walls around domestic financial systems.

In turn, European regulators threatened to retaliate… In short, regulators throughout the world, in an attempt to make their own financial system safer, are raising barriers and fragmenting the global financial system. But as this new research demonstrates, reducing the ability of banking groups to move funds around is weakening both global and domestic financial systems, not strengthening them.

I find bewildering that regulators don’t seem to get that logic. Let’s imagine that Bank X, based in the UK, has a subsidiary that shares the same name in the US. The US authorities believe that by making the US-based subsidiary stronger it will make it less likely to fail. Fair enough. Let’s now imagine that Bank X in the UK is experiencing difficulties and need to recover some funds located in its US sub to ensure its survival. Unfortunately, US rules prevent this transfer and Bank X effectively collapses. Do US regulators really believe that the US sub will remain untouched? Even if looking solid locally, this sub suffers massive reputational and operational damages from the collapse of its parent. This is likely to trigger a downward spiral, if not an outright bank run on those US operations. The original goal of the US authorities was thus self-defeating.

While such regulations can indeed make domestic subsidiaries look stronger, this isn’t the case on a consolidated basis. We have another fallacy of composition example here. None of those regulatory requirements can ever make banks fully crisis-proof. Consequently, when a truly large crisis strikes, healthy banks won’t be able to support their struggling sister banks, which can potentially even endanger their own existence through indirect contagion.

Even during non-crisis times, banks, and in turn economies, get penalised by those measures as banks’ cost of funding rises to reflect the inherent higher riskiness of each subsidiary/parent companies, making credit either more scarce and/or expensive.

Coincidentally, I am currently reading Fragile by Design, a new book by Calomiris and Haber, which argues that nations’ political frameworks influence the design of local banking systems and that some political arrangements (including the one in the US) are more prone to banking collapses. I guess current events are proving them right…

There are other, ‘counterintuitive’, solutions to stability in banking (which, guess what, involve less government intervention in banking, not more). Unfortunately, what we are currently witnessing is the sacrifice of competition in banking on the altar of instability… In the end, everybody loses.

* I should add that a lot of losses in investment banking divisions actually emanated from structured products (RMBS, CDOs) based on… dodgy retail lending. Nonetheless, those losses were marked-to-market and only few structured products outright defaulted (see also here). But mark-to-market losses, even when temporary, are enough to make a bank insolvent, according to current IFRS and US GAAP accounting rules.

** I am however a little curious about the claim of the authors that this result contradicts economic theory. I don’t know what ‘economic theory’ they are referring to, but those results look fully logical to me. Banking groups know what part of the group lacks liquidity. Because of reputational reasons, they have a clear incentive to transfer extra liquidity to struggling subsidiaries/divisions/holding companies. Letting a part of the group collapse is likely to trigger a dangerous chain reaction for the whole group.

Update: I modified the title of this post to more accurately reflect the content and the follow-up posts

A new regulatory-driven housing bubble?

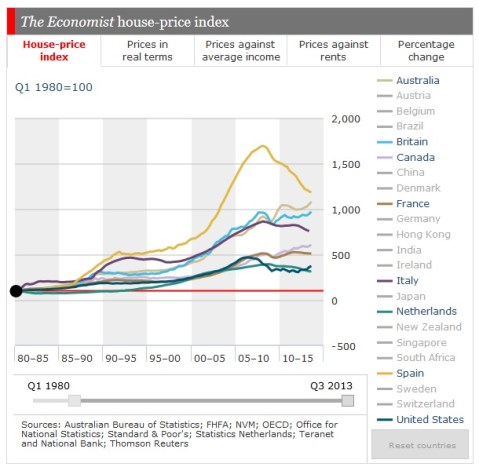

There is nothing surprising at all in what’s happening. As I have already pointed out several times, Basel regulations are still incentivising banks to channel the flow of new lending towards property-related sectors. A repeat of what happened, again and again, since the end of the 1980s, when Basel was first introduced. I cannot be 100% certain, but I think this is the first time in history that so many housing markets in so many different countries experience such coordinated waves of booms and busts.

So far we’ve had two main waves: the first one started when Basel regulations were first implemented in the second half of the 1980s. It busted in the first half of the 1990s before growing so much that it would make too much damage. The second wave started at the very end of the 1990s, this time growing more rapidly thanks to the low interest rate environment, until it reached a tragic end in 2006-2008. It now looks like the third wave has started, mostly in countries where house prices haven’t collapsed ‘too much’ during the crisis.

Sam Bowman was indeed right that lack of supply (through planning restrictions) is a real factor in driving up house prices in the UK. However, this cannot be the only issue at play here. A chronic lack of supply would lead to chronically increasing housing prices, not to wave-like variations, especially when those waves happen to be very well coordinated with those of other countries.

I still have to dig more in details into the data of each country, and I’ll do it in subsequent posts. For sure, some countries seemed to ‘skip’ one wave or to experience a mild one, but banking regulation is only part of the explanation. Local factors such as monetary policy, population growth, building restrictions, etc., are also important in determining local prices.

What’s interesting in the FT article is also the fact that a lot of countries have implemented macro-prudential policies over the last few years. Their effects on house bubbles seemed to have been close to nil… Indeed, low real interest rates compounded by regulatory-boosted mortgage lending supply still make housing an attractive asset class.

As long as this deadly combination remains in place, brace yourself for a recurring pattern of housing bubble cycles.

RWA-based ABCT Series:

- Banks’ risk-weighted assets as a source of malinvestments, booms and busts

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Update

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – A graphical experiment

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Some recent empirical evidence

- A new regulatory-driven housing bubble?

What most people seem to have missed about high-frequency trading

I finished reading Michael Lewis’ new book Flashboys last week. I wasn’t a specialist of high-frequency trading (HFT) at all, so I found the book interesting. Overall, it was an easy read. Perhaps too easy. I am always suspicious of easy-to-read books and articles that supposedly describe complex phenomena and mechanisms. Flashboys partly falls in that trap. Lewis has a real talent to entertain the reader. He unfortunately often slightly exaggerates and attacks the HFT industry without giving them the opportunity to respond. More annoyingly, the whole book reads like a giant advertising campaign for IEX, the new ‘fair’ exchange set up by Brad Katsuyama. In the end, I was left with a slightly strange aftertaste: the book is very partisan. I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised.

The book, as well as HFT, have been the topic of much discussion over the past few weeks*. I won’t come back to most of those comments, but I wish here to highlight what many people seem to have missed. Lewis, as well as many commenters, drew the wrong conclusions from the recent HFT experience. They misinterpret both the role of regulation and the market process itself.

What is most people’s first answer to the potential ‘damage’ caused by HFT? Regulation. I would encourage those people to read the book a second time. Perhaps a third time. This is Lewis:

How was it legal for a handful of insiders to operate at faster speeds than the rest of the market and, in effect, steal from investors? He soon had his answer: Regulation National Market System. Passed by the SEC in 2005 but not implemented until 2007, Reg NMS, as it became known, required brokers to find the best market prices for the investors they represented. The regulation had been inspired by charges of front-running made in 2004 against two dozen specialists on the floor of the old New York Stock Exchange – a charge the specialists settled by paying a $241 million fine.

Bingo.

Until 2007, brokers had discretion over how to handle investors’ trade orders. Despite the few cases of fraud/front-running, most investors didn’t seem to particularly hate that system. In a free market, investors are free to change broker if they are displeased with the service provided by their current one. At the very least, nothing seemed to really justify government’s intervention to institutionalise and regulate the exact way brokers were supposed to handle trade orders. In fact, when government took private discretion away, investors started feeling worse off. This is the very topic of the book (though Lewis didn’t seem to notice): government and regulation created HFT.

Brad Katsuyama sums it up pretty well (emphasis mine):

I hate them [HFT traders] a lot less than before we started. This is not their fault. I think most of them have just rationalized that the market is creating inefficiencies and they are just capitalizing on them. Really, it’s brilliant what they have done within the bound of regulation. They are much less a villain than I thought. The system has let down the investor.

Brad is definitely less naïve than Lewis, who still believed in the power of regulation throughout his book**:

Like a lot of regulations, Reg NMS was well-meaning and sensible. If everyone on Wall Street abided by the rule’s spirit, the rule would have established a new fairness in the U.S. stock market.

Meanwhile, David Glasner questioned the ‘social value’ of HFT on his blog:

Lots of other people have weighed in on both sides, some defending high-frequency trading against Lewis’s accusations, pointing out that high-frequency trading has added liquidity to the market and reduced bid-ask spreads, so that ordinary investors are made better off, not worse off, as Lewis charges, and others backing him up. Still others argue that any problems with high-frequency trading are caused by regulators, not by high-speed trading as such.

I think all of this misses the point. Lots of investors are indeed benefiting from the reduced bid-ask spreads resulting from low-cost high-frequency trading. Does that mean that high-frequency trading is a good thing? Um, not necessarily.

I believe that here it is Glasner who completely misses the point. Should we blame HFT traders from exploiting loopholes created by regulation? Economists are better placed than anyone to know that people respond to economic incentives. The resources ‘wasted’ by HFT on ‘socially useless informational advantages’ emanate from government intervention. It is highly likely that HFT would have never developed under its current form should Reg NMS had not been passed. What we instead witness is another case of regulatory-incentivised spontaneous financial innovation.

The second problem lies in the fact that most people seem to have become particularly impatient and dependent on short-term (and short-sighted) regulatory interventions. They spot a new ‘problem’ in the way markets work (here, HFT) and highlight it as a ‘market inefficiency’. This evidently cannot be tolerated any longer and regulators need to intervene right now to make markets ‘fairer’ (putting aside the fact that they were the ones who created this ‘inefficiency’ in the first place).

This demonstrates a fundamental misinterpretation of the market process. Markets’ and competitive landscapes’ adaptations aren’t instantaneous. This allows first movers to take advantage of consumers/investors demand and/or regulatory loopholes to generate supernormal profits… temporarily. In the medium term, the new economic incentives attract new entrants, which progressively erode the first movers’ advantage.

This occurs in all industries. Financial firms are no different (assuming no government protection or subsidies). And, despite Lewis’ outrage at HFT firms’ super profits, the fact is… that the mechanism I just described has already applied to them. It was reported that the whole industry experienced an 80% fall in profits between 2009 and 2012 (which Tyler Cowen had already ‘predicted’ here).

Besides, the story the book tells is a pure free-market story: a group of entrepreneurs wish to offer an alternative platforms to investors who also decide to follow them. There is no government intervention here. The market, distorted for a little while, is sorting itself out. Even the big banks see the tide turning and start switching sides (Goldman Sachs is depicted in a relatively positive light in the book). Lewis’ book itself is also part of that free-market story: the finger-pointing and informational role it plays is a necessary feature of the market process. To me, this demonstrates the ability of markets to right themselves in the medium-term. Patience is nevertheless required. It unfortunately seems to be an increasingly scarce commodity nowadays.

There was a very good description of HFT and its strategies published by Oliver Wyman at the end of last year (from which the chart below is taken). Surprisingly, they described HFT’s strategies and the effects of Reg NMS before the publication of Lewis’ book, without unleashing such a public outcry…

* See some there: FT’s John Gapper, The Economist, David Glasner, Noah Smith, Zero Hedge, Tyler Cowen (and here), ASI’s Tim Worstall, as well as this new paper by Joseph Stiglitz, who completely misinterprets the market process. See also this older, but very interesting, article by JP Koning on Mises.org on HFT seen through both Walrasian and Mengerian descriptions of the pricing process.

I also wish to congratulate Bob Murphy for this magical tweet:

** This is also despite Lewis reporting this hilarious dialogue between Brad Katsuyama and SEC regulators (emphasis his):

When [Brad, who had just read a document describing how to prevent HFT traders from front-running investors] was finished, an SEC staffer said, What you are doing is not fair to high-frequency traders. You’re not letting them get out of the way.

Excuse me? said Brad

And to continue saying that 200 SEC employees had left their government jobs to go work for HFT and related firms, including some who had played an important role in defining HFT regulation. It reminded me of this recent study that showed that SEC employees benefited from abnormal positive returns on their securities portfolios…

The obsession of stability

One of the outcomes of the financial crisis has been that regulators are now obsessed with instability. Or stability. Or both.

They have been on a crusade to eliminate the evil risks to ‘financial stability’, and nothing seems to be able to stop them (ok, not entirely true). Banks, shadow banking, peer-to-peer lending, crowdfunding, private equity, payday lenders, credit cards…

Their latest target is asset managers. In a new speech at London Business School, Andrew Haldane, a usually ‘wise’ regulator, seems to have now succumbed to the belief that regulators know better and have the powers to control and regulate the whole financial industry (see also here). This is worrying.

Haldane now views every large asset manager as dangerous and many investment strategies as potentially amplifying upward or downward spiral in asset prices, representing ‘flaws’ in financial markets that regulators ought to fix. I believe this is strongly misguided.

In their quest to cure markets from any instability, regulators are annihilating the market process itself. I would argue that some level of instability is not only necessary, but is also desirable.

First, instability reflects human action; the allocation of resources by investors and entrepreneurs. Some succeed, some fail, prices go up, prices go down, everybody adapts. Sometimes many, too many, investors believe that a new trend is emerging, indeed amplifying a market movement and subsequently leading to a crash. But crashes and failures are part of the learning process that is inherent to any capitalist and market-based society. Suppress or postpone this process and don’t be surprised when very large crashes occur. On the other hand, an unhampered market would naturally limit the size of bubbles and their subsequent crashes as market actors continuously learn from their mistakes.

Second, instability enhances risk management. Instability is necessary because it induces fear in markets participants’ behaviour, who then take risks more seriously. By suppressing instability, regulators would suppress risk assessment and encourage risky behaviours: “there is nothing to fear; regulators are making sure markets are stable.” The illusion of safety is one of the most potent risks there is.

Nevertheless, regulators, on their quest for the Holy Grail of stability, want to regulate again and again. On the back of flawed instability or paternalistic consumer protection arguments, and despite seemingly showing poor understanding of financial industries, they are trying to implement regulations that would at best limit, at worst dictate, market actors’ capital allocation decisions. Adam Smith would turn in his grave (along with his invisible hand, who is now buried next to him).

In the end, regulators’ obsession for stability and protection creates even stronger systemic risks. In fact, the only ‘stable’ society is what Mises called the evenly-rotating economy, the one that never experiments. Nothing really attractive.

Funny enough, in his speech, Haldane even acknowledged regulation as one of the reasons underlying some of the current instability:

Risk-based regulatory rules can contribute further to these pro-cyclical tendencies. […]

There have been several incidences over recent years of regulators loosening regulatory constraints to forestall concerns about pro-cyclical behaviour in a downswing. […]

In particular, regulation and accounting appear to have played a significant role.

I guess he didn’t get the irony.

Mobile banking keeps growing, payday lenders perhaps not so much anymore

The Fed published last week a new mobile banking survey in the US. Here are the highlights: 33% of all mobile phone owners have used mobile banking over the past twelve months, up from 28% a year earlier. When only considering smartphones, those figures increased to 51% and 48% respectively, with 12% of mobile users who plan to move on to mobile banking soon. 39% of the ‘underbanked’ population used mobile banking over the period. Checking balances, monitoring transactions and transferring money are the most common activities.

Still more than half of mobile users who do not currently use mobile banking are reluctant to use it in the future though. But usage is correlated with age. 18 to 29yo users represent 39% of all mobile banking users but only 21% of mobile phones users, whereas 45 to 60yo represent 27% of mobile banking users but 53% of mobile users. I am indeed not surprised by those results, and, as I have described in a previous post, as current young people age, the bank branch will slowly disappear and mobile banking become the norm. (Bloomberg published an article on the end of the bank branch yesterday)

That the underbanked naturally benefit from mobile banking isn’t surprising, and isn’t new at all. The widespread use of the M-Pesa system in Kenya rested on the fact that a very large share of the population had no or limited access to banking services. However, some African countries with slightly more developed banking systems are resisting the introduction of mobile money in order not to interfere with the business as usual of the local incumbent banks. Another case of politicians and regulators acting for the greater good of their country. Anyway, mobile money/banking is now instead making its way to… Romania, as almost everyone there owns a mobile phone but more than a third of the population does not have access to conventional banking.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the regulators are doing what they can to clamp down on payday lenders. As I have described in a previous post, the result of this move is only likely to prevent underbanked people from accessing any sort of credit, as other regulations seriously limit mainstream banks’ ability to lend to those higher-risk customers.

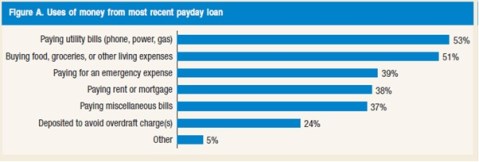

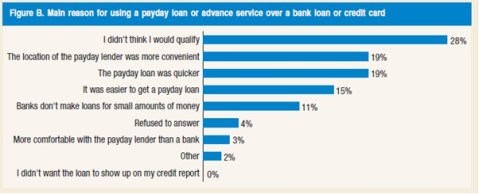

Here again, the Fed mobile banking survey is quite enlightening. They asked underbanked people their reasons for using payday lenders. Here are their answers:

Right… So what are the consequences when you prevent people from temporarily borrowing small amount of cash that their bank aren’t willing to provide and who need it to pay for utility bills or buying some food or for any other emergency expenses? It looks like regulators believe that those families would indeed be better off not being able to pay their water bills.

Of course, over-borrowing is an issue (as are abuse and fraud), but regulators are merely clamping down on symptoms here. Society is confronted with a dilemma: either those households are unable to pay their bills or buy enough food, or they might face over-indebtedness… None of those two options are attractive. But in such a situation, it is customers’ responsibility to choose. If they can avoid payday lenders, so they should. If they really can’t, this option should remain on the table. Sam Bowman from the Adam Smith Institute made very good comments on BBC radio Wales earlier today (see here from 02:05:00) on this topic.

I know I am repeating myself, but you cannot regulate problems away.

A central banker contradiction?

Last week, Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, was at Cass Business School in London for the annual ‘Mais Lecture’. Coincidentally, I am an alumnus of this school. And I forgot to attend… Yes, I regret it.

Carney’s speech was focused on past, current, and future roles of the BoE. In particular, Carney mentioned the now famous monetary and macroprudential policies combination. It’s a classic for central bankers nowadays. They all have to talk about that.

In January, Andrew Haldane, a very wise guy and one my ‘favourite’ regulators, also from the BoE, made a whole speech about the topic. As Jens Weidmann, president of the Bundesbank, did in February.

I am not going to come back to the all the various possible problems caused and faced by macroprudential policies (see here and here). However, there seems to be a recurrent contradiction in their reasoning.

This is Carney:

The transmission channels of monetary and prudential policy overlap, particularly in their impact on banks’ balance sheets and credit supply and demand – and hence the wider economy. Monetary policy affects the resilience of the financial system, and macroprudential policy tools that affect leverage influence credit growth and the wider economy. […]

The use of macroprudential tools can decrease the need for monetary policy to be diverted from managing the business cycle towards managing the credit cycle. […]

That co-ordination, the shared monitoring of risks, and clarity over the FPC’s tools allows monetary policy to keep Bank Rate as low as necessary for as long as appropriate in order to support the recovery and maintain price stability. For example expectations of the future path of interest rates – and hence longer-term borrowing costs – have not risen as the housing market has begun to recover quickly.

First, it is very unclear from Carney’s speech what the respective roles of monetary policy and macroprudential policies are. He starts by saying (above) that “monetary policy affects the resilience of the financial system”, then later declares “macroprudential policy seeks to reduce systemic risks”, which is effectively the same thing. At least, he is right: both policy frameworks overlap. And this is the problem.

This is Haldane:

In the UK, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has been pursuing a policy of extra-ordinary monetary accommodation. Recently, there have been signs of renewed risk-taking in some asset markets, including the housing market. The MPC’s macro-prudential sister committee, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC), has been tasked with countering these risks. Through this dual committee structure, the joint needs of the economy and financial system are hopefully being satisfied.

Some have suggested that having monetary and macro-prudential policy act in opposite directions – one loose, the other tight – somehow puts the two in conflict [De Paoli and Paustian, 2013]. That is odd. The right mix of monetary and macro-prudential measures depends on the state of the economy and the financial system. In the current environment in many advanced economies – sluggish growth but advancing risk-taking – it seems like precisely the right mix. And, of course, it is a mix that is only possible if policy is ambidextrous.

Contrary to Haldane, this does absolutely not look odd to me…

Let’s imagine that the central bank wishes to maintain interest rates at a low level in order to boost economic activity after a crisis. After a little while, some asset markets start looking ‘frothy’ or, as Haldane says, there are “renewed signs of risk-taking.” Discretionary macroprudential policy (such as increased capital requirements) is therefore utilised to counteract the lending growth that drives those asset markets. But there is an inherent contradiction here: one of the goals that low interest rates try to achieve is to boost lending growth to stimulate the economy…whereas macroprudential policy aims at…reducing it. Another contradiction: while low interest rates tries to prevent deflation from occurring by promoting lending and thus money supply growth, macroprudential policy attempts to reduce lending, with evident adverse effects on money supply and inflation…

Central bankers remain very evasive about how to reconcile such goals without entirely micromanaging the banking system.

I guess that the growing power of central bankers and regulators means that, at some point, each bank will have an in-house central bank representative that tells the bank who to lend to. For social benefits of course. All very reminiscent of some regions of the world during the 20th century…

Weidman is slightly more realistic:

We have to acknowledge that in the world we live in, macroprudential policy can never be perfectly effective – for instance because safeguarding financial stability is complicated by having to achieve multiple targets all at the same time.

Indeed.

Photograph: Intermonk

Recent Comments