Research on macro-prudential regulation: barely any effect

I promised last time a new post on macro-prudential regulation. Here it is. I recently reviewed six academic publications and noticed a curious fact: while most, if not all, of those papers conclude that some macro-prudential policies can have some effects on some asset prices or credit growth, they remain quite careful in their conclusions and are often aware of the limitations of their methodology. However, when other papers refer to them (usually in their literature review), they always overemphasise the apparent successes of those policies and avoid mentioning their shortcomings and limitations almost entirely. Consequently, a reader that would only open one of those research papers would only see macropru under an overwhelmingly positive light.

But, don’t be mistaken, it is not what most of those researchers said. Their conclusions are usually much more nuanced than the depiction and oversimplification we hear in the media and in the mouth of other academics and central bankers.

The first paper, published in 2011 by IMF staff, titled Macroprudential Policy: What Instruments and How to Use Them? Lessons from Country Experiences, was an early attempt at looking at the economic effects of macropru. While thick, the paper is clearly not comprehensive and a number of its findings were in opposition with findings of later research.

Running a cross-country regression analysis on data from 49 countries, they found that a number of macropru instruments were effective in dampening procyclicality. Most ‘effective’ instruments were targeting particular products or asset classes (i.e. LTV or DTI caps), although they did find that fluctuating reserve requirements helped, in contradiction with other papers.

Importantly, they stress that there are ‘costs’ involved in using those instruments. That is, potentially lower economic growth or ‘unintended distortions’. They also point out that macropru could be subject to regulatory and cross-border arbitrage and show that discretionary decision-making, rather than rules, dictate the use of those policies. Finally, they also warn against using macropru as an alternative to monetary policy in order to address ‘excess demand’, and subsequent research has indeed shown that macropru is no substitute for monetary instruments. They do not research any of those issues.

Debunking the myth that macropru was a ‘new’ tool for central bankers, they show that many, many countries has already utilised them before the crisis.

My main issue with this paper is that, similarly to another macropru research paper I reviewed in a previous post, it takes correlations way to literally. For instance, it says that macropru was successfully used in China to limit credit and house price growth, and in Spain to help cover the large losses of the financial crisis. Well, it seems to me that, those ‘successes’ have been rather poor given how severely Spanish banks suffered during the crisis and how rapidly credit growth has been since the implementation of those measures in China… I would at best call this a ‘quarter-success’, and this, even without even looking at the potential credit allocation distortions macropru has brought about in those countries.

Moreover, their correlations are not fully convincing: from some of their charts, it seems that the implementation of a macropru measure was sometimes followed by no effect for a while, or in other cases, that the implementation only occurred after a change in credit growth trend (see chart below).

The second paper, published in 2012 also by IMF staff, is titled Macroprudential Policies and Housing Prices – A New Database and Empirical Evidence for Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. This one is more targetted, both in term of geography and in terms of target (housing prices). Here again they show that many countries had been using macropru for quite some time, and that it didn’t help them much preventing crises.

They find that some macropru measures, such as raising minimum regulatory capital ratios, did have an impact on house price growth, while others, such as increasing reserve requirements or dynamic provisioning, did not. However, those effects only slow down the housing cycle rather than stop or reverse it, and more importantly, they are temporary. Growth seems to reaccelerate a few months after their introduction. Their study does not look beyond this short timeframe.

Curiously, and in contradiction with a later study (see below), they find that easing regulatory capital requirements helped dampen the effects of a crisis.

The authors also show that different countries demonstrate different macropru ‘activism’ (see chart below), and that, as expected, a number of measures adopted were procyclical, amplifying the crisis. Clearly, this is a major weakness for macro-prudential policies.

Overall, this paper does not look at whether macropru leaks in a way or another, but does show that its effectiveness is limited and temporary, and that it is clearly subject to usual problems of discretionary policies and central planning.

The third paper, published in 2013 by BIS staff, is titled Can non-interest rate policies stabilise housing markets? Evidence from a panel of 57 economies. Like the previous one, the scope of this paper is limited to housing markets. But at least it allows us to easily compare their results in order to check the consistency of those findings.

The authors used two types of regressions to assess the effects of certain types of macropru tools affecting the supply side (reserve/liquidity requirements, limits on credit growth, risk weighting and provisioning requirements, limits on housing sector exposure) or the demand side (cap on LTV and debt service to income and housing-related taxes).

What did they find? Not much:

From a policy perspective, the negative results are in some respects as important as the positive ones. One such finding is that instruments affecting the supply of credit generally by increasing the cost of providing housing loans (reserve and liquidity requirements and limits on credit growth) have little or no detectable effect on the housing market. Nor do risk weighting and provisioning requirements, which target the supply of housing credit. Exposure limits, which work not by the cost of lending but through the quantity restrictions on banks’ loan supply, may be an exception in this regard, although the small number of documented policy actions makes it hard to draw firm conclusions. Measures aimed at controlling credit supply are therefore likely to be ineffective.

Of the two policies targeted at the demand side of the market, the evidence indicates that reductions in the maximum LTV ratio do less to slow credit growth than lowering the maximum DSTI ratio does. This may be because during housing booms, rising prices increase the amount that can be borrowed, partially or wholly offsetting any tightening of the LTV ratio. None of the policies designed to affect either the supply of or the demand for credit has a discernible impact on house prices. This has implications for the degree to which credit-constrained households are the marginal purchasers of housing or for the importance of housing supply, which is not explicitly considered in this study. Only tax changes affecting the cost of buying a house, which bear directly on the user cost, have any measurable effect on prices.

In other words, apart from increasing taxes on housing (which isn’t really macropru), none of the macro-prudential instruments studied had any actual effect on housing prices. This doesn’t sound very positive. Moreover, due to the narrow scope of the paper, it doesn’t look at potential distortions resulting from the same policies.

Interestingly, the paper provides a quite comprehensive database of macro-pru and tax-related measures taken since the 1980s (see below). After seeing this, I’m really unsure how macropru proponents can still claim this type of regulation is new and effective.

The fourth paper (another IMF staff one) was published in 2014 and is titled Macro-Prudential Policies to Mitigate Financial System Vulnerabilities. Looking at a database of 2,800 banks in 48 countries, they analyse the balance sheet response to various types of macro-prudential tools during the 2000-2010 period. A quick remark first of all: they seem to only use USD balance sheet figures, which I find surprising given that year-on-year FX fluctuations would affect their conclusions. They don’t seem to be controlling for this effect, but I might have misread.

They find

in particular caps on borrower and financial institutions assets and liabilities–based measures to be effective, while buffer-based policies seems to have little impact on asset growth. Overall, there is little evidence that the effectiveness of these tools varies by the intensity of the cycle.

Caps on borrowers (LTV, DTI…) are confirmed to have an effect, in line with some of the studies above (although the end goal remains to control housing price growth, and the previous study seems to show that this was not happening). However, the effect is small to say the least: banks’ asset growth was reduced by 0.44% in average. More surprisingly, they find that countercyclical capital buffers not only have little effects on credit growth, but also

do not help to provide cushions that alleviate crunches during downswings. As such, macro-prudential tools may be less promising to mitigate adverse events.

This is a major issue for regulators as countercyclical buffers and dynamic provisioning have been mostly advertised as helping alleviate a downturn by making banks more solid, thereby providing continuity to the flow of credit to the economy.

Finally, they find that macropru has been mostly used by closed capital countries, which have less liberalised financial systems. This makes sense as there are then fewer opportunities for those measures to ‘leak’. But this has not prevented many of those developping countries to experience crises anyway.

More recently (end-2015), BoE staff published a piece titled Regulatory arbitrage in action: evidence from banking flows and macroprudential policy. The piece is interesting because it demonstrates how regulatory arbitrage within a macro-prudential framework. It is based on a database of banking flows in 37 countries (but not on individual banks data), between 2005 and 2014.

They find that macropru measures that do not apply to all banks within a certain country suffer from leakages. This is possible because, apart from countercyclical buffers, Basel 3 do not impose cross-border regulatory coordination. Consequently, macropru tools that affect capital levels only apply to domestic banks and domestic subsidiaries of foreign banks, but not to branches of foreign ones. The result is an increase in foreign borrowing by domestic corporates when capital constraints are tightened for the domestic banking system.

However, when macropru tools (such as tigthening of lending standards) apply indiscrimenately to all banks within a given jurisdiction, they find no evidence of this cross-border borrowing (the charts they present aren’t as clear cut, even though the effect is clearly weaker – see below). Evidence is mixed when reserve requirements are varied.

More worryingly, their conclusion points to macropru regulation as a major driver of cross-border capital flows through regulatory arbitrage:

This suggests that uneven application of regulation may be a driver of international capital fows. This is over and above the effect, which has been documented extensively in the literature, where banks transfer funds to markets with fewer banking regulations. Our results show a subtle contrast: banks transfer funds to countries which tighten regulatory standards, but transfer these funds when the regulatory tightening does not apply to them, and instead confers upon them a competitive advantage.

Finally, the latest paper I rewiewed, published in January 2016 by BIS staff, is titled Is macroprudential policy instrument blunt?. The paper seems to suffer from a ‘correlation does not imply causation’ issue. It focuses on Japan from the 1970s to the 1990s, as local authorities used a policy instrument called ‘quantitative restriction’ (QR), which requires banks to reduce their real estate lending.

I won’t spend long on this paper as I believe it doesn’t bring much to the literrature given its reliance on what seems to be spurious correlations. We all know the booms that Japan experienced in the 1980s. We also all know that when this boom turned into a burst, the whole economy collapsed. Does this have anything to do with the implementation of QR? Unlikely. Yet this is what the researchers who wrote this paper seem to say, as they write that “QR affected the aggregate economy by damaging the balance sheet of banks and non-financial sectors”. Unless it was the crisis.

In the end, it does look like the evidence that macro-prudential policies are effective is rather inconclusive. Some seem to have minor effects, temporarily, providing one does exclude potential leakages and distortions and believes in the timely implementation of those tools by regulators. Others seem to have no effect whatsoever. And worse, academics seem to reach different conclusions regarding the exact same instruments.

Yet, the literrature review section of many of those papers depicts macropru in rather positively. Take the fourth paper listed above. Referring to the first paper listed in this post, it says that its authors “document evidence of some policie being effective in reducing the procyclicality of credit and leverage.” Well, I had a slightly different reading.

To be fair, they do also report the relatively negative results of some other studies (such as the third one above). This is in stark contrast with most central bankers and regulators, who describe macro-prudential regulation under an overwhelmingly positive light, and who would like us to believe that enlightened policymakers manipulating macropru can solve all the problems that their own misguided monetary policy creates, independently of any Public Choice issue. Let’s not believe.

PS: you can see my take on a few other research reports on macro-prudential instruments, and on the fact that macropru cannot offset the damages of monetary policy, here, here and here.

Dampening crises: cross-border lending and risk-weights

I’ve been reviewing tons of academic papers recently, hence why you see me posting a lot of research reviews. I’ll have a specific post on macro-prudential policy next week hopefully, but today I wish to briefly mention an interesting October 2015 paper from Philippe Bacchetta and Ouarda Merrouche: Countercyclical Foreign Currency Borrowing: Eurozone Firms in 2007-2009.

The piece is interesting because it refers to two topics I have covered at length on this blog: the importance of international financial integration and cross-border lending (implying the importance of not restricting cross-border intragroup capital and liquidity flows), as well as the negative impact of Basel’s risk weights on lending to corporations.

They looked at how a tightening domestic credit supply during a crisis impacted firms that wished to borrow. They found that reduced credit appetite from European banks led riskier corporates to switch to US banks as funding source, which in turn dampened the effects of the crisis on those firms:

We decompose our empirical analysis into three steps. In a first step we verify that foreign credit is countercyclical: when Eurozone banks tighten lending standards, riskier borrowers are more likely to obtain a loan from a foreign bank rather than from a domestic bank. We find that this effect at the intensive margin is attributable to US banks. The willingness of US banks to replace Eurozone banks can be explained by the fact that during this period and until 2012 US lenders operated fully under Basel I. Under the Basel I framework, the risk weight on risky and safe corporate debt is the same. This means that US banks have greater incentive than Eurozone banks to load onto risky corporate debt.

Did you read that? They believe that US banks were more at ease with lending to riskier borrowers because Basel 1’s risk-weights (and therefore capital requirement) were the same for both risky and safe corporates. Regulatory arbitrage at its best. This again demonstrates how Basel’s risk weights distorted the allocation of credit in the economy, as explained literally millions of times on this blog.

They then concluded that transitioning to Basel 2 subsequently made the crisis worse:

The way bank capital is regulated appears to play an important role in the process. The fact that US banks operated under Basel I meant that they had an incentive to shift to riskier corporate loans when Eurozone banks retrenched. Our analysis therefore illustrates how the move from Basel I to Basel II with risk-sensitive capital requirements has contributed to amplify the credit cycle. Basel III goes some way towards addressing the problem through the introduction of mandatory buffers, a capital preservation buffer and a countercyclical buffer, that are built-up in good times and can be released in bad times to avoid a credit crunch.

I wouldn’t agree so much with their statement about Basel 3 however, which relies on the fact that regulatory authorities would be able to foresee and/or correctly assess the economic situation and take the right decisions at the right times; something some of the studies about macro-prudential policies I recently read warned about (more in a following post). A clear knowledge dispersion issue.

Finally, what this paper emphasises is the importance of cross-border lending in dampening the effects of a credit crunch. As I described in my series on intragroup funding, regulators have been trying to silo liquidity and capital in each separate banking groups’ legal entity. I believe this is misguided as it will limit or prevent cross-border funding flows and therefore the ability of subsidiaries to extend credit in foreign countries when necessary. And by attempting to strengthen each separate subsidiary, regulators are likely to make groups as a whole weaker.

PS: I spent a couple of hours earlier this week drafting a post warning against over-interpreting temporary market movements, following a few posts on the topic written by Scott Sumner (see here, here and here). I eventually decided against, as I have written about the topic before and I just couldn’t bother (perhaps I’ll change my mind later). Let’s just say that seeing market movements in the seconds or minutes following an announcement as an indicator of how markets perceived this announcement is a massive misinterpretation of the way financial markets and trading (and even worse now: HFT) work. No market actor has the ability to instantaneously process and analyse complex new information (that is why there are economists, analysts, and other commentators to enlighten market makers and investors). If EMH is valid, it is certainly not within a few minutes timeframe.

In the comment section of one of his posts, he even mentioned the wisdom of crowds as a benefit of democracy. As if Public Choice theory had never existed. No don’t get me started. Please.

Political connection and bank performance

This is a short post about a curious, but interesting, paper I recently read. Titled The dark side of political connection: Exchange easy loans for the political career of bank CEOs, and written by Chen, Hasan, Lin and Yen (CHLY thereafter), the paper demonstrates that banks with political connections underperformed ‘independent’ ones during the crisis.

This probably won’t come as a surprise to many of you. A quick read through Calomiris and Haber’s Fragile by Design shows the critical and disastrous influence of politics on banking and economic performance. Still, the paper is worth a look as it provides further empirical evidence.

CHLY define ‘government banks’ as banks with at least 20% state ownership. They then subdivide this group into two: those with CEOs that served as politicians are called ‘political banks’ and the other ones are ‘non-political banks’. A first comment: I believe their sample underestimate political connections. They probably only pick banks that have the strongest connections. There are non-state-owned banks whose CEOs used to be or have subsequently become politicians, or have been to school with current government officials and have very close links with them. Their sample doesn’t capture such cases. Weirdly, their sample seems to exclude countries such as the US, UK or Germany. No reason is provided.

Based on this admittedly limited dataset, they analyse the evolution of the asset quality, as well as a number of performance indicators (return on equity and assets, cost/income…), of those banks during the crisis. They find that

Political banks significantly approve more low-quality loans than non-political banks, such that they are confronted with a higher ratio of nonperforming loans to gross loans during the crisis. This ratio indicates that politically connected banks become increasingly inefficient and pursue a more risky lending behavior. Further, these lower quality loans cause significant underperformance as measured by the return on assets, return on equities, net interest income to total assets, and the cost to income ratio during the crisis years.

CHLY also find that institutional framework, low corruption, strong governance, and institutional ownership mitigate the impact of political connection on the agency problem. ‘Non-political government banks’ also seem to be partly protected from most of the bad effects that plague ‘political banks’.

Moreover, they find that politically-connected CEOs grant more low quality loans for their own benefit, and that many of those CEOs (almost 30%) were offered political jobs after the crisis. They conclude that

the politically connected CEOs, who have poor operating performance, are less likely to be penalized by the bank or politics. They even have a bright future political career after the crisis. This evidence is consistent with our political connection hypothesis that these CEOs use their power and influence to relax lending standards and reap private benefits.

And some people still question the conclusions of the Public Choice school… Worse, many others want to nationalise the money creation framework (see Positive Money), falsely believing in a fully independent central bank that would always act for the greater good. Others want to nationalise the whole banking system, as if this recipe had never been tried before. Go figure.

Basel capital requirements, labour reallocation and productivity

Last week I wrote two posts about recent research on the impact of Basel’s capital requirements on mortgage pricing and sovereign bond demand, which I believed were evidence of Basel enabling an ‘Austrian-type’ business cycle. Today, this is the last post of this mini-series, and it covers another great research report published by Claudio Borio and his team: Labour reallocation and productivity dynamics: financial causes, real consequences.

As often with Borio, this is a great paper. And it does seem to provide further evidence of Basel allowing distorted allocation of credit with dramatic economic consequences. However, I do need to point out that the paper does not explicitely point at Basel as the cause of the misallocation (but instead supposes that collateral availability plays a role). Rather, this is my own interpretation of it. The correlation looks pretty strong.

The paper looks at forty years of credit and productivity data across 20 advanced economies. It finds that

the decline in the allocation component during credit booms overwhelmingly reflects shifts in employment towards low productivity growth sectors. […] In other words, credit booms do not appear to affect the sectoral distribution of productivity gains, turning potentially high productivity growth sectors into low productivity growth ones. Rather, they induce labour shifts into lower productivity growth sectors. Productivity in industries with rapid long-run productivity growth does not grow any more slowly during credit booms, but these industries attract relatively fewer workers.

So credit booms and/or change in the allocation of credit do not alter the inherent productivity of each sector but rather shift labour between sectors. They also find that “labour reallocation is quantitatively the main channel through which credit booms affect productivity.” The key question being: which sectors benefit, and at the expense of which ones?

And here, the answer couldn’t be clearer (my emphasis):

The results suggest that manufacturing and construction are the two sectors primarily responsible for the slowdown. When either sector is withdrawn, the negative correlation goes away or at least weakens compared with the benchmark case. Interestingly, removing the financial sector does not affect our results.

Combining this result with the previous one, the conclusion is clear. Aggregate productivity slows down during credit booms primarily because employment expands more rapidly in the construction sector, which structurally features low productivity growth. And employment expands more slowly or contracts in manufacturing, which is structurally a high productivity growth sector.

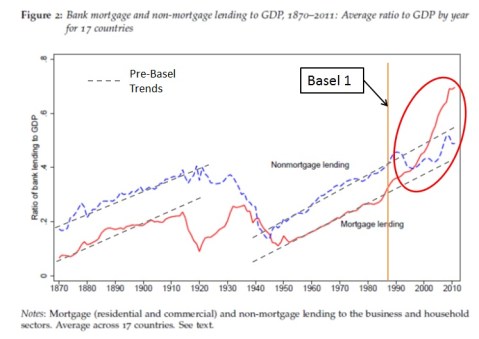

This is in line with what I would expect given that Basel’s capital requirements favour real estate lending over other types. Remember this chart from Jorda et al, which I modified:

Coincidence? Highly unlikely I believe. Although it still isn’t fully clear why manufacturing suffers more than other non-real estate sectors, and this deserves further investigation.

Moreover, they find that once a crisis hits, this misallocation of capital and labour leads to a painfully slow recovery as post-crisis productivity growth is reduced.

They reached a few, but highly important, conclusions, which I have already mentioned on this blog a number of times.

First, they believe that the ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis should be seen under a different light:

Our findings suggest a different mechanism, in which the slow recovery after the Great Financial Crisis is the result of a major financial boom and bust, which has left long-lasting scars on the economic tissue (eg BIS (2014), Rogoff (2015)). More specifically, they suggest that what some see as a comparatively disappointing US growth performance in the pre-crisis years, despite a strong financial boom, was actually disappointing, in part, precisely because of the boom. And so has been the post-crisis weak productivity growth.

They also warn about the effects of monetary policy in such a world, which could amplify the misallocation:

Nor is it surprising if monetary policy may not be particularly effective in addressing financial busts. This is not just because its force is dampened by debt overhangs and a broken banking system – the usual “pushing-on-a-string” argument. It may also be because loose monetary policy is a blunt tool to correct the resource misallocations that developed during the previous expansion, as it was a factor contributing to them in the first place.

While a number of economists would argue that current monetary policy isn’t loose, the argument still stands. Loose or not, the allocation of credit still occurs through Basel’s lens. And Borio ends this paper by highlighting that there may be a mechanism that distorts credit allocation that he hasn’t yet uncovered. Well, perhaps banking regulation would be a good starting point for further research. Unfortunately, Borio works for the BIS, which devised our whole bank regulatory framework…

Basel capital requirements and sovereign bond demand

This is the second post of this short series reviewing recent research on the distortions introduced by the Basel banking framework, in light of the ‘RWA-based ABCT’. Two days ago I focused on the influence of capital requirements on mortgage pricing. Today I’m going to focus on a new quite interesting (albeit predictable?) piece of research that looks at the influence of the Basel framework on the demand for government bonds (see Preferential Regulatory Treatment and Banks’ Demand for Government Bonds by Clemens Bonner, see also Voxeu summary article here).

Bonner not only analyses the effects of capital requirements, but also of liquidity requirements, mostly introduced by the post-crisis Basel 3 accords. His dataset comprises Dutch banks (which were subject to a Dutch equivalent to Basel 3’s Liquidity Coverage Ratio, the ‘DLCR’). To identify whether banks’ demand for government bonds is caused by regulatory or internal risk management effects, he hypothesises that a change in demand around reporting date is likely to imply that regulatory reporting is the main driver.

He first looks at the impact of liquidity rules (the x-axis represents days of the month, and increased demand for the asset is represented by a descending curve):

If a bank’s regulatory liquidity position affects its net purchases of government bonds over the entire month, it cannot be established whether this effect comes from regulation or from internal risk management targets. With the DLCR affecting banks’ net purchases only from day 18 onwards, it can be concluded that there is limited evidence of an internal effect incentivizing banks with lower liquidity holdings to purchase more government bonds or sell more other bonds. The combined evidence of the DLCR affecting banks’ demand only towards the end of the month and the slopes presented in Figure 5 show clear signs of a regulatory effect, suggesting that the DLCR incentivizes banks to substitute government bonds for other bonds.

He then applies the same logic to capital ratios:

Similar to liquidity, Figure 6 shows that the regulatory capital position is an important determinant of banks’ net purchases of government bonds. One can see that a lower regulatory capital ratio in the previous month causes banks to buy considerably more government bonds and sell more other bonds.

He concludes:

Our results suggest that preferential treatment in microprudential capital and liquidity regulation increases banks’ demand for government bonds. On top of that, it seems to cause a substitution effect, with banks buying more government bonds while selling more other bonds. Further, we find suggestive evidence that this “regulatory reaction” reduces banks’ lending.

As expected, it’s pretty clear that sovereign bonds, thanks to their preferential regulatory treatment (no capital required and quasi-obligation to hold them as part of your high-quality liquid assets portfolio) boosted the demand for them. This, in turn, should have depressed their yields and allowed governments to benefit from lower interest rate than in an unhampered market. Low yields are always good for debt binges.

Worse, and also as expected, the increase in demand for those bonds led to a decrease in demand for corporate bonds, which is likely to have had the opposite effects on yields and on the profitability and investments of those firms.

PS: I think I should rename the ‘RWA-based ABCT’ into ‘Basel ABCT’. The RWA name was mostly valid in pre-Basel 3 times but now that Basel 3 has introduced extra ways of distorting demand, supply and yields, ‘Basel ABCT’ sounds more appropriate.

Basel capital requirements and mortgage pricing

Do we still need evidence that Basel’s capital requirements distort interest rates and capital allocation in the economy? Yes we do. We need as much evidence as we can in order to present a bulletproof case against current banking regulation.

I have argued since this blog’s inception that the pricing distortions hardwired in Basel’s framework led to fundamental misallocations that could trigger economic crises (the ‘RWA-based ABCT’) and progressively provided empirical evidence in support of this case. Just a few weeks ago, I reported that recent (and not so recent) pieces of research were (unsurprisingly in my opinion) attacking Basel on the ground that it unnecessarily penalised SME lending.

This post is the first of a series of three new short posts covering research papers published over the past few months which, you guessed it, seem to add to this growing body of evidence.

The first one, titled Higher Bank Capital Requirements and Mortgage Pricing: Evidence from the Countercyclical Buffer (CCB), is also the first paper I read that shows that macro-prudential regulation could have some effect! Although this effect is limited and it is unclear (and uncontrolled) if credit growth cannot happen through other channels.

But what I’m interested in is the impact of the countercyclical buffer (CCB), a macro-prudential tool that allows policymakers to adjust capital requirements according to where in the economic cycle they believe we stand. It’s all discretionary and they will often get it wrong (assuming they are not influenced by politics) of course, but at least it allows us to live test the reactions of private actors to this exogenous constraint and measure the resulting distortion in credit supply and pricing.

In this case, Switzerland raised the CCB for mortgage lending only, leaving other sorts of lending untouched, which effectively tightened the spread between mortgage capital requirements and the rest. Remember that mortgage (or sovereign) lending benefited from much lower capital requirements than corporate lending, making it more profitable at equal levels of risk to extend credit for real estate purposes. In theory, and given a fixed money supply, this incentive should lead to increased mortgage supply and lowered interest rates on mortgage products. Hence, a reduction in the capital differential would likely reduce the supply of mortgage and/or raise interest rates.

So what did the paper find? That the CCB was changing the composition of mortgage supply and raising mortgage interest rates:

Results […] point out that capital-constrained banks raise their rates relatively more after the CCB’s regulatory shock than do their unconstrained peers. In line with the joint estimation, these constrained banks now charge on average 2.72 bp more which reflects their tradeoff between approaching the now even closer intervention threshold and additional profits. The constrained indicator is not statistically significant in either estimation.

Results […] reveal that banks that specialize in the mortgage business increase their mortgage rates after the CCB activation by on average 5.57bp relative to non-specialized competitors. Higher capital requirements force banks to hold more equity capital for each mortgage already on their balance sheets. Some of that additional cost on their existing portfolio is passed on to new customers. Again, the specialized indicator is insignificant in both regressions

This is encouraging evidence, although not comprehensive. It would have been interesting to find out whether or not other sorts of lending benefited from changes in their supply and/or pricing.

Regarding the conclusion that the CCB might be an effective macro-pru tool, the paper did not control for domestic or international leakage (i.e. credit growth through other channels) and it remains to be seen whether or not banks are not willing to go down the risk scale in order to extract higher rates for the same amount of capital (which would come at the expense of financial stability down the line).

A few thoughts for JPK on negative rates and AD

Following my post on negative rates and banking instability, JP Koning commented and left a very interesting question:

Are you of the opinion that a rate cut into negative territory would reduce aggregate demand?

First, I’d like to apologise to JP for the very late reply. I had a crazy past week (for those who don’t know, I compete in powerlifting)…

While drafting an answer, I came to the conclusion that I should actually write a very short post as this might be of interest to a number of my readers. Here are some of my thoughts:

I think it’s tricky to answer. It will vary a lot depending on local factors and local culture.

But I believe that, if ever negative rates provide a boost to demand, it will be minimal and not worth the risk of extra financial instability it creates.

But quantitatively it’s really hard to say.

Some of the factors involved are (I’m surely missing a few other ones):

– Are banks going to charge retail customers or not?

– If they do, what is the local propensity to save more/spend more/withdraw cash/change nothing in response, and in which amplitude?

– Also, how will this affect the turnover on banks’ deposit base, and hence their funding stability, as deposits have traditionally been among the most stable funding sources. In line with the theory of my previous post, empirical evidences show that banks with less stable funding structures tend to contract their lending more (or at least grow their loan book more slowly) in periods of stress (see this very interesting paper by Ivashina and Scharfstein for instance). And less lending implies less demand.

– If not, how are banks going to deal with the decline in profitability while having to implement seriously disrupting banking reforms and generate extra capital to comply with regulatory requirements, while still retaining their shareholder base? Banks without shareholders just disappear. And an economy without banks usually doesn’t perform very well.

– Also, in order to prevent their RoE from evaporating, what is going to be the propensity of profitability-constrained banks to start hunting for extra yield by lowering underwriting standards, potentially endangering medium to long-term financial stability? And I fear that, in such case, banks would once again get blamed for the resulting crisis, leading to even more government intervention in the financial system. This can’t be good.

So there cannot be a definitive answer to JP’s question, with local culture and banking characteristics being determinant factors.

Negative interest rates and banking instability

Negative interest rates are back in the news as they seem to be generalising. This is a topic I have covered several times over the past couple of years.

Back in June 2014 in particular, I wrote two posts about negative interest rates on ECB deposits. Here, I explained the negative impacts of this policy on banks, from an accounting and profitability perspective. I concluded:

Many European banks aren’t currently lending because they are trying to implement new regulatory requirements (which makes them less profitable) in the middle of an economic crisis (which… also makes them less profitable). As a result, the ECB measures seem counterproductive: in order to lend more, banks need to be economically profitable. Healthy banks lend, dying ones don’t.

The ECB is effectively increasing the pressure on banks’ bottom line, hardly a move that will provide a boost to lending. The only option for banks will be to cut costs even further. And when a bank cut costs, it effectively reduces its ability to expand as it has less staff to monitor lending opportunities, and consequently needs to deleverage. Once profitability is re-established, hiring and lending could start growing again.

Subsequently, I wrote about the fact that some German banks had started charging their non-retail customers for holding deposits with them. I started with the following bank’s (basic) economic profit equation introduced in the post mentioned above:

Economic Profit = II – IE – OC – Q

where II represents interest expense, IE interest income, OC operating costs (which include impairment charges on bad debt), and Q liquidity cost.

From this equation, I showed how banks attempted to pass negative deposit interest expenses onto some customers, thereby neutralising the effect the ECB was expecting, that is: lending growth.

But of course, ECB economists aren’t that clueless, and knew that this could happen. So they hoped that a second effect could ‘stimulate’ aggregate demand: that customers believe themselves to be better off spending their money (pushing inflation up) rather than getting effectively taxed.

Unfortunately, this relies on

- a simplistic and very mechanical view of human beings, and

- a flawed understanding of banking mechanics.

I addressed point 2 in several posts. In a banking system relatively free of regulatory constraints, as banks’ customers attempt to spend as quickly as possible after getting their salary paid in, the velocity of the money supply increases, but so does banks’ liquidity cost (Q in the equation above). Why? Because banks’ funding structure becomes more unstable, leading them to accumulate more low-risk, liquid assets as a share of total assets in order to face possible adverse clearing and in order to reduce the liquidity mismatch between the growing turnover of their deposit base and their longer-term investments.

Worse, if customers do not spend but instead merely decide to withdraw their deposits and keep their cash under their mattress, not only is bank’s funding structure more unstable, but it also shrinks, leaving banks with fewer funds to ‘lend out’.

In both case, credit supply (particularly long-term) is likely to get affected and bank shareholders/bondholders are likely to require higher returns to offset what they perceive as higher liquidity risk. Given that returns are already pretty depressed, no wonder I recently said that banks were bleeding shareholders.

Moreover, recent banking regulation amplifies this phenomenon. Basel 3 introduced the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) and the net stable funding ratio (NSFR), which require banks to hold a certain type and amount of liquid assets and ‘stable’ funding on their balance sheet to face short-term withdrawals. From the instability and increased deposit turnover I described above, it seems obvious that those rules would further constraint banks’ ability to freely decide how to allocate credit (and how much).

Those are conclusions I reached already two years ago. Am I the only one to hold such view? Apparently not, given what a number of analysts have recently said. According to The Telegraph:

Sub-zero rates would discourage banks from expanding their operations, crimp cross-border lending in the eurozone and result in higher credit costs in the beleaguered currency bloc, according to Morgan Stanley.

“This is all contrary to the ECB’s desire to ease credit conditions and support financial stability,” said Mr van Steenis.

“It is an unnecessary and dangerous experiment to take in case there are non-linear impacts on deposit stability and financials stability writ large.

“The ECB’s action is flipping from a positive to a negative for European banks,” he added.

What about point 1 above? Well, a recent survey by ING provides some colour as to how people would react if nominal rates on their saving accounts turned negative (real rates have often been negative but, you know, money illusion).

Those are some of the results:

The chart doesn’t show the percentage who responded ‘spending more’. So here is the answer (my emphasis):

No less than 77% said that they would take their money out of their savings accounts if rates went negative. But only 12% would spend more, with most suggesting that they would either switch into riskier investments or hoard cash ‘in a safe place’.

So much for raising inflation…

Of course, once effectively facing negative rates, those respondents might behave differently, but the survey highlights that the effects of the policy on aggregate demand may not end up as positive as central banks expect, while harming the banking system and hence making it less able to lend for productive purposes.

PS: However, and as usual, I strongly disagree with Frances Coppola’s assertion (about excess reserves) that:

But of course the reserves do not disappear from the system. They simply move to another bank, which then incurs the tax. The banking system AS A WHOLE cannot avoid negative rates on reserves.

No, as I and George Selgin recently described, if the whole system extends credit, excess reserves gets converted into required ones. Hence the tax disappears. Nevertheless, this is a lengthy process, as operationally, it is almost impossible for banks to increase their loan book/buy assets quickly enough to offset the recent extremely rapid growth in the monetary base, in particular at a time of new regulatory implementation. (please note that this reasoning only applies to policies that only charge negative rates on excess reserves)

PPS: I also wrote about whether or not a free banking system would ever apply negative rates here.

Banking and social justice don’t mix very well

I recently came across the following piece from Tony Greenham on the RSA website: “Banks should serve the real economy – How?”

It’s something I have often read in the media, most of the time written by people who don’t really understand the purpose of banking in the economy. It often comes from a certain part of the political spectrum, and seems to be a cover for ‘social justice’ applied to banking. And it’s a recipe for disaster.

The argument is typical: banking should be ‘fair’ and ‘serve the real economy’. Yet, as with social justice in general, no definition is ever provided of what ‘fair’ banking is and how it can more adequately help the real economy. As with ‘social justice’, all criteria of fairness inevitably remain very subjective and variable in time, place and individual mood. Moreover, what a number of people view as ‘fair’ is often in direct contradiction with the rule of law.

All this logic comes down to the view that banking is another type of ‘utility’. That it should provide services for all that need them. No, it isn’t. Banks do not have a duty to provide credit on demand. Forcing them to do so would inevitably lead to bad lending decisions and hence large losses, and politicians and the public would once again blame those ‘greedy’ bankers who took senseless risks (despite encouraging them in the first place). This is what happened in the US with subprime mortgages (and the Community Reinvestment Act Greenham seems to find useful). See Calomiris and Haber’s Fragile by Design to understand the serious implications that ‘fairness’ had on the US banking system before the crisis.

Greenham’s post falls into the same trap. Let’s leave aside the fact that his post is technologically quite backward-looking (branches and transactions are now increasingly replaced by mobile phones and technologies like blockchain, and the shrinking number of customers using branches can continue to do so) and also avoid any discussion of modern constraints on banking; that is: regulation (branches are great if you can cover the cost of operating them).

He blames banks, free markets and ‘co-ordination failure’ for the disappearance of branches whereas he should have focused on ballooning regulatory and compliance bills that accelerate that change beyond the pace justified by technological transformation.

But where I am really worried is when I read this:

But bank deposits are underwritten by the state. Their acceptability depends on the state. They are arguably therefore a public good. Certainly, how much money is created in total, and to which economic sectors it is lent, are matters of the highest public interest. So here is the problem – there is no guarantee that if you add up all the individual lending decisions of banks that you will arrive at the optimal level of credit growth and allocation for the economy.

In fact, theoretical and empirical evidence suggests the opposite. We see too much credit creation during booms, and too little during recessions. Too much credit flowing to real estate and financial asset speculation, and too little to SMEs and infrastructure investment.

Individual banks cannot solve this problem. More competition cannot solve this problem. Rigid free-market ideology cannot solve this problem.

This is the sort of superficial thinking that I have tried to fight since I started writing on this blog. Typically, this sort of ‘social justice’ reasoning never tries to dig a little deeper below the surface. This would lead to dreadful conclusions: that the proposed solution (i.e. often government intervention) would actually target outcomes of previous government intervention. So better avoid digging altogether and coming to terms with unpleasant findings, and continue to believe that banking is ‘inherently unstable’ and doesn’t know how to efficiently allocate capital in the economy without the guiding hand of government officials.

The usual Public Choice and Hayekian critiques also apply. The information fragmentation and political incentives prevent policymakers from taking the right decisions in a timely fashion. Moreover, the highly subjective and fluctuating ‘social justice’ criteria lead to discretionary decision-making and regulatory uncertainty. This does not represent a recipe for economic success.

So what to do? Set banking free. The ‘invisible hand’ behind bankers’ lending decision will, on aggregate, allocate credit in more effective manner than any central authority and its distorted and ever changing incentives ever can. There is a reason behind the financial and real estate booms of the last few decades. And it lies in artificial rules designed by a number of ‘great minds’. Not in a ‘rigid free-market ideology’ that never was.

PS: we could say a lot about his assertion that deposits are a public good, but it isn’t the topic of this post.

Banks are bleeding shareholders

There has been a lot of discussion about the bank stock sell-off in the media. A lot of analysts and journalists have been wondering what’s going on in face of what looks like an overreaction. I don’t have an answer to that question, as I’m not sure that fundamentals justify that sell-off. Perhaps some hedge funds and speculators have been temporarily amplifying the fluctuations. But I’m not omniscient and it is possible markets have noticed something that I missed.

What I believe though, is that this sell-off has been artificially exacerbated by traditional bank shareholders, who can’t stand that situation anymore, in particular in Europe. What I mean by ‘that situation’ is everything that’s been happening to the banking sector since the crisis.

Imagine that you’re a bank shareholder. The bank you invested in survived the crisis but stopped paying dividends to you and left you with a deep negative return on your portfolio of shares. In order to start growing again and comply with new regulatory requirements, the bank asks you to invest more capital, promising a return to profitability soon. You are glad the institution survived the crisis, which may signal its superior risk management relative to competitors, so you provide that extra capital.

Unfortunately, regulation tightens further and central banks push interest rates down, sometimes into negative territory, compressing the bank’s net interest margin and depressing its profitability. To cope with this temporary pressure, the bank asks you to invest a little bit more capital, possibly in one of those new fancy hybrid capital instruments that pay high coupons without diluting the equity holder base. Fine you think, it’s for a good reason: this will be a temporary pain to bear in order to stimulate the economy and make the financial system safer, which should soon lead to prospects of higher and more stable return.

Unfortunately, authorities and regulators in a multitude of countries believe this time to be appropriate to fine banks, including yours, for past and current misbehaviour, leading to your bank’s capitalisation weakening again. A little bit annoyed, you tell yourself that it is the last time you inject extra capital into that bank. And anyway, what else could happen? You’ve pretty much lived through everything now.

Unfortunately, far from improving under all the central bank stimulus, the economy of a number of countries start declining, leading to fears for the world economy. In case of a global, or multi-country, recession, the banking sector is likely to make some losses, prompting some investors to sell their shares. As a result, the bank you invested in is likely to ask you for some extra capital sooner or later. No gain on your portfolio is in sight. “I’m out” you say, fed up.

The past eight years have been so badly managed by policymakers, central bankers and regulators, that I hope it’s going to enter history books as a good example of what not to do following a large systemic financial crisis.

Whether or not one wishes to increase the regulatory oversight of the financial sector, the worst possible time to do it is while surviving banks’ health remains extremely weak. Bankers, not only have to deal with legacy issues on their own balance sheet, but also have to implement fundamental and very disruptive changes to the same balance sheet.

Add in very low internal capital generation due to depressed profitability in a low interest rate environment (and amid the exit of a number of now unprofitable businesses), as well as huge fines that literally disintegrate capital*, and you end up with a banking sector that cannot comply with regulators’ constant demands without continuously raising capital from their existing (or new) shareholders without ever rewarding them.

Policymakers seem not to have understood one of the main tenets of capitalism: opportunity cost. There is no point, as an investor, to become a shareholder in an institution that cannot generate even close to its cost of capital in the long run. And, relative to 2008, the long run is now.

As I have repeatedly said on this blog, you can’t get a healthy economy without a healthy banking system. And a healthy banking system implies generating return around the cost of capital. It does not imply bashing banks and trying to transform them regardless of the consequences over a fifteen-year period.

In an effort to strengthen the banking system’s balance sheet and punish bankers for their alleged past behaviour, policymakers have forgotten the most important component of the system, without which there is no bank in the first place: the shareholder.

Without shareholder, no private enterprise. And banks are starting to bleed shareholders.

*To be fair, a few regulators have been complaining about the lack of coordination between regulatory agencies:

I am trying to build capital in firms, and it is draining out down the other side.

Recent Comments