MC Klein and central bankers struggle to understand banking mechanics

I recently pointed out that many central bankers actually did not understand banks’ internal mechanics. We now have further evidence. In an FT Alphaville blog post, Matthew Klein quoted a recent report from the Reserve Bank of Australia, which usefully compared banking metrics across countries.

MCK points out that Australian banks have some of the lowest cost/income ratios in the world, whereas Swiss, German and British banks have some of the highest ones. According to the report, the difference mostly comes from the lower income paid to Australian bankers, which (apparently) originates in the ‘simplicity’ of Australian banks, whose investment banking activities are relatively small.

Indeed, as the following chart demonstrates, Australian banks do generate a larger share of their revenues from net interest income than banks in other countries. MCK concludes:

In other words, the more a bank focuses on taking in deposits and making loans to households and businesses, the cheaper it is to run and the less money its employees make.

And he then quotes the Australian central bank:

The Australian major banks’ focus on commercial banking – that is, lending to households and businesses – appears to be a contributor to their relatively low CI ratio. In 2013, those large banks that earned a greater share of their income from net interest income (a proxy for a bank’s focus on lending activities) tended to have lower CI ratios than ‘universal’ banks, which earned a larger share of their income through non-interest sources such as investment banking or wealth management.

The above analysis suggests that there may be diseconomies of scope for some large banks – that is, average costs increase as they diversify outside of commercial banking services. This is consistent with some literature which points to negative returns to scope when banks move into market-based activities. While market-based activities can provide a more diversified revenue stream for banks, they are typically a more volatile source of income and can expose banks to additional risks and complexity.

As simple as that.

But… wait. Are things really that simple?

Let’s take a look at some of the largest banks’ reported segmental cost/income ratios in 2013*. The segments in bold are the ones that include ‘simple’ retail banking:

- UBS: its reported segmental cost/income ratios were the following in 2013: Wealth Management 70%, Wealth Management Americas 87%, Retail & Corporate 61%, Global Asset Management 70%, Investment Bank 73%

- Credit Suisse: Wealth Management 75%, Corporate & Institutionals 51%, Asset Management 69%, Investment Banking 71%

- Deutsche Bank: Corporate Banking & Securities 76%, Global Transaction Banking 65%, Asset & Wealth Management 83%, Private & Business Clients 76%

- Commerzbank: Private Customers 90%, Mittlestandbank 46%, Central & Eastern Europe 54%, Corporates & Markets 65%, Non-Core Assets 98%

- Barclays: UK RBB 67%, Barclaycard 43%, Africa RBB 71%, Europe RBB 126%, Wealth 87%, Investment Bank 72%, Corporate 58%

It is really not clear that straightforward retail banking boasts low cost/incomes. And if one thing is clear, it is that, even in their retail banking divisions, banks in Europe do not boast the same sort of cost/income as in Australia, far from that. Around 20 percentage points higher in fact. Small, retail-only, European banks’ cost/income ratios also reach the 60 to 75% level.

Perhaps the complexity/simple story isn’t that straightforward after all.

While it is true that investment banking, in theory, can lead to higher cost/income ratios (as can private banking), and that banking systems that rely on such activities inherently have bigger cost bases, this does not mean that those banking systems are necessarily unprofitable. Switzerland for instance has a very large number of private banks. The private banking business model leads to high level of costs… and low level of risk. In a bank’s income statement, loan impairment charges follow operating costs. A bank whose asset quality is low needs the financial flexibility to absorb losses on its loan portfolio. Hence the importance of a low cost/income. Many emerging markets banks indeed have low cost/income ratios.

That was the first point: cost/income by itself doesn’t mean much.

Second point is… by focusing on the cost side of the equation, both MCK and the Australian central bankers forgot the income side.

The income side comprises net interest income. This net interest income is partly dependent on the level of interest rates. When rates are set at a low level by central banks, margin compression appears. I have already described this phenomenon here. Unfortunately this concept seems to be foreign to most people.

Banks in the UK and Europe have been suffering from margin compression for many years, as interest rates have dropped near their zero lower bound, leading lending rates to fall while (deposit) funding rates were already stuck at the bottom. Many banks in the UK and the Eurozone now only have net interest margins of 1% or less. When margins are low, net interest income suffers and accounts for a lower share of total income.

What happened in Australia in the meantime? Well, interest rates are now at a record low of…2.5%. What are banks’ net interest margins? 2% to 2.25%… Given how strong those margins are, it is natural that Australian banks will also boast higher net interest incomes, and in turn higher incomes and lower cost/income ratios…

We now have a more comprehensive answer than the ‘simple’ (if not simplistic) explanation offered in this FT Alphaville column: low rates are partly responsible for European and American banks’ high cost/income ratio. ‘Complexity’, on the other hand, is an easy and convenient target for regulators. It fits the story they’ve been trying to sell since the crisis. Facts, unfortunately, are a little more stubborn.

* Segments aren’t fully comparable. Some include corporate/SME lending or wealth management, others not. Some one-offs could distort some of the figures somewhat. I didn’t correct for that. Some banks already exclude them from their reported segmental cost/income or include them in ‘non-core’ or ‘non-strategic’ units.

Why the Austrian business cycle theory needs an update

I have been thinking about this topic for a little while, even though it might be controversial in some circles. By providing me with a recent paper empirically testing the ABCT, Ben Southwood, from ASI, unconsciously forced my hand.

I really do believe that a lot more work must be done on the ABCT to convince the broader public of its validity. This does not necessarily mean proving it empirically, which is always going to be hard given the lack of appropriate disaggregated data and the difficulty of disentangling other variables.

However, what it does mean is that the theoretical foundations of the ABCT must be complemented. The ABCT is an old theory, originally devised by Mises a century ago and to which Hayek provided a major update around two decades later. The ABCT explains how an ‘unnatural’ expansion of credit (and hence the money supply) by the banking system brings about unsustainable distortions in the intertemporal structure of production by lowering the interest rate below its Wicksellian natural level. As a result, the theory is fully reliant on the mechanics of the banking sector.

The theory is fundamentally sound, but its current narrative describes what would happen in a relatively free market with a relatively free banking system. At the time of Mises and Hayek, the banking system indeed was subject to much lighter regulations than it is now and operated differently: banks’ primary credit channel was commercial loans to corporations. The Mises/Hayek narrative of the ABCT perfectly illustrates what happens to the economy in such circumstances. Following WW2, the channel changed: initiative to encourage home building and ownership resulted in banks’ lending approximately split between retail/mortgage lending and commercial lending. Over time, retail lending developed further to include an increasingly larger share of consumer and credit card loans.

Then came Basel. When Basel 1 banking regulations were passed in 1988, lending channels completely changed (see the chart below, which I have now used several times given its significance). Basel encouraged banks’ real estate lending activities and discouraged banks’ commercial lending ones. This has obvious impacts on the flow of loanable funds and on the interest rate charged to various types of customers.

In the meantime, banking regulations have multiplied, affecting almost all sort of banking activities, sometimes fundamentally altering banks’ behaviour. Yet the ABCT narrative has roughly remained the same. Some economists, such as Garrison, have come up with extra details on the traditional ABCT story. Others, such as Horwitz, have mixed the ABCT with Yeager’s monetary disequilibrium theory (which is rejected by some other Austrian economists).

While those pieces of academic work, which make the ABCT a more comprehensive theory, are welcome, I argue here that this is not enough, and that, if the ABCT is to convince outside of Austrian circles, it also needs more practical, down to Earth-type descriptions. Indeed, what happens to the distortions in the structures of production when lending channels are influenced by regulations? This requires one to get their hands dirty in order to tweak the original narrative of the theory to apply it to temporary conditions. Yet this is necessary.

Take the paper mentioned at the beginning of this post. The authors find “little empirical support for the Austrian business cycle theory.” The paper is interesting but misguided and doesn’t disprove anything. Putting aside its other weaknesses (see a critique at the bottom of this post*), the paper observes changes in prices and industrial production following changes in the differential between the market rate of interest and their estimate of the natural rate. The authors find no statistically significant relationship.

Wait a minute. What did we just describe above? That lending channels had been altered by regulation and political incentives over the past decades. What data does the paper rely on? 1972 to 2011 aggregate data. As a result, the paper applies the wrong ABCT narrative to its dataset. Given that lending to corporations has been depressed since the introduction of Basel, it is evident that widening Wicksellian differentials won’t affect industrial structures of production that much. Since regulation favour a mortgage channel of credit and money creation, this is where they should have looked.

But if they did use the traditional ABCT narrative, it is because no real alternative was available. I have tried to introduce an RWA-based ABCT to account for the effects of regulatory capital regulation on the economy. My approach might be flawed or incomplete, but I think it goes in the right direction. Now that the ABCT benefits from a solid story in a mostly unhampered market, one of the current challenges for Austrian academics is to tweak it to account for temporary regulatory-incentivised banking behaviour, from capital and liquidity regulations to collateral rules. This is dirty work. But imperative.

Major update here: new research seems to confirm much of what I’ve been saying about RWAs and the changing nature of financial intermediation.

* I have already described above the issue with the traditional description of the ABCT in this paper, as well as the dataset used. But there are other mistakes (which also concern the paper they rely on, available here):

– It still uses aggregate prices and production data (albeit more granular): the ABCT talks about malinvestments, not necessarily of overinvestment. The (traditional) ABCT does not imply a general increase in demand across all sectors and products. Meaning some lines of production could see demand surge whereas other could see demand fall. Those movements can offset each other and are not necessarily reflected in the data used by this study.

– It seems to consider that aggregate price increases are a necessary feature of the ABCT. But inflation can be hidden. The ABCT relies on changes in relative prices. Moreover, as the structure of production becomes more productive, price per unit should fall, not increase.

Kupiec on central banking/planning

In the WSJ a couple of days ago, Paul Kupiec wrote an article that looks so similar to my blog that I had to quote it here.

Macroprudential regulation, macro-pru for short, is the newest regulatory fad. It refers to policies that raise and lower regulatory requirements for financial institutions in an attempt to control their lending to prevent financial bubbles. […]

There is also the very real risk that macroprudential regulators will misjudge the market. Banks must cover their costs to stay in business, and in the end bank customers will pay the cost banks incur to comply with regulatory adjustments, regardless of their merit. By the way, when was the last time regulators correctly saw a coming crisis?

He concludes with:

With Mr. Fischer now heading the Fed’s new financial stability committee, might we soon see regulations requiring product-specific minimum interest rates? Or maybe rules that single out new loan products and set maximum loan maturities and debt-to-income limits to stop banks from lending on activities the Fed decides are too “risky”? None of these worries is an unimaginable stretch.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, U.S. bank regulators have put in place new supervisory rules that limit banks’ ability to make specific types of loans in the so-called leverage-lending market—loans to lower-rated corporations—and for home mortgages. Since there is no scientific means to definitively identify bubbles before they break, the list of specific lending activities that could be construed as “potentially systemic” is only limited by the imagination of financial regulators.

Few if any centrally planned economies have provided their citizens with a standard of living equal to the standard achieved in market economies. Unfortunately the financial crisis has shaken belief in the benefits of allowing markets to work. Instead we seem to have adopted a blind faith in the risk-management and credit-allocation skills of a few central bank officials.

Government regulators are no better than private investors at predicting which individual investments are justified and which are folly. The cost of macroprudential regulation in the name of financial stability is almost certainly even slower economic growth than the anemic recovery has so far yielded.

This is very good, and I can’t agree more.

He points to his own research on macro-prudential policies. In a paper published in June 2014, Kupiec, Lee and Rosenfeld declare that

Compared to the magnitude of loan growth effects attributable to [increase in supervisory scrutiny or losses on loan/securities], the strength of macroprudential capital and liquidity effects are weak. This data suggest that traditional monetary policy (lowering banks’ cost of funding) is likely to be a much more potent tool for stimulating bank loan growth following widespread bank losses than modifying regulatory capital or liquidity requirements.

(note: they also say that the opposite logic applies)

While it doesn’t mean that they are wrong, I am not fully convinced by their arguments, especially given the dataset they base their analysis on (an economic and credit boom period, with less than tight monetary policy and many variables that could have been distorted as a result). In another paper, Aiyar, Calomiris and Wieladek point to the fact that macro-prudential policy can be effective at reducing banks’ lending, but that alternative sources of credit (i.e. shadow banking) grow as a result (they say that macro-prudential policies ‘leak’).

What is clear is that the effects of macro-prudential policies are unclear. What is also clear is that, whatever the effects of those policies, none are necessarily desirable. If macropru is indeed effective, then the resulting distorted capital allocation may be harmful. If macropru isn’t effective, then it may lead central bankers to (wrongly) believe they can maintain interest rates below/above their natural level while controlling the collateral damages this creates. In both cases the economy ends up suffering.

ECB policies: from flop to flop… to flop?

Even central bankers seem to be acknowledging that their measures aren’t necessarily effective…

ECB’s Benoit Coeuré made some interesting comments on negative deposit rates in a speech early September. Surprisingly, he and I agree on several points he makes on the mechanics of negative rates (he and I usually have opposite views). Which is odd. Given the very cautious tone of his speech, why is he even supporting ECB policies?

Here is Coeuré:

Will the transmission of lower short-term rates to a lower cost of credit for the real economy be as smooth? While bank lending rates have come down in the past in line with lower policy rates, there is a limit to how cheap bank lending can be. The mark-up that banks add to the cost of obtaining funding from the central bank compensates for credit risk, term premia and the cost of originating, screening and monitoring loans. The need for such compensation does not necessarily fall when policy rates are lowered. If anything, a central bank lowers rates when the economy needs stimulus, which is precisely when it is difficult for banks to find good loan making opportunities. It remains to be seen whether and to what extent the recent monetary policy accommodation translates into cheaper bank lending.

This is a point I’ve made many times when referring to margin compression: banks are limited in their ability to lower the interest rate they charge customers as, absent any other revenue sources, their net interest income necessarily need to cover their operating costs (at least; as in reality it needs to be higher to cover their cost of capital in the long run). Banks’ only solution to lower rates is to charge customers more for complimentary products (it has been reported that this is in effect what has been happening in the US recently).

Negative rates are similar to a tax on excess reserves, which evidently doesn’t make it easier for a bank to improve its profitability, and as a result its internal capital generation. And Coeuré agrees:

A negative deposit rate can, however, also have adverse consequences. For a start, it imposes a cost on banks with excess reserves and could therefore reduce their profitability. Note, however, that this applies to any reduction of the deposit rate and not just to those that make the rate negative. For sure, lower bank profitability could hamper economic recovery, especially in times when banks have to deleverage owning to stricter regulation and enhanced market scrutiny. But whether bank profitability really falls when policy rates are lowered depends more generally on the slope of the yield curve (as banks’ funding costs may also fall), on banks’ investment policies (as there is scope for them to diversify their cash investment both along the curve and across the credit universe) and on factors driving non-interest income.

Coeuré clearly understands the issue: central banks are making it difficult for banks to grow their capital base, while regulators (often the same central bankers) are asking banks to improve their capitalisation as fast as possible. Still, he supports the policy…

Other regulators are aware of the problem, and not all are happy about it… Andrew Bailey, from the Bank of England’s PRA, said last week that regulatory agencies should co-ordinate:

I am trying to build capital in firms, and it is draining out down the other side.

This says it all.

Meanwhile, and as I expected, the ECB’s TLTRO is unlikely to have much effect on the Eurozone economy… Banks only took up EUR83m of TLTRO money, much below what the central bank expected. It is also likely that a large share of this take up will only be used for temporary liquidity purposes, or even for temporary profitability boosting effects (through the carry trade, by purchasing capital requirement-free sovereign debt), until banks have to pay it off after two years (as required by the ECB, and without penalty, if they don’t lend the money to businesses).

Fitch also commented negatively on TLTRO, with an unsurprising title: “TLTROs Unlikely to Kick-Start Lending in Southern Europe”.

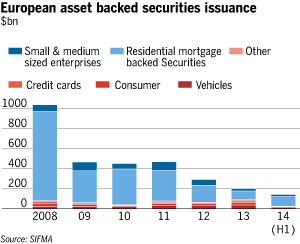

Finally, the ECB also announced its intention to purchase asset-backed securities (which effectively represents a version of QE). While we don’t know the details yet, the scheme has fundamentally a higher probability to have an effect on banks’ behaviour. There is a catch though: ABS issuance volume has been more than subdued in Europe since the crisis struck (see chart below, from the FT). The ECB might struggle to buy the quantity of assets it wishes. Perhaps this is why central bankers started to encourage European banks to issue such structured products, just a few years after blaming banks for using such products.

Oh, actually, there is another catch. ABSs are usually designed in tranches. Equity and mezzanine tranches absorb losses first and are more lowly rated than senior tranches, which usually benefit from a high rating. Consequently, equity and mezzanine tranches are capital intensive (their regulatory risk-weight is higher), whereas senior tranches aren’t. To help banks consolidate their regulatory capital ratios and prevent them from deleveraging, the ECB needs to buy the riskier tranches. But political constraints may prevent it to do so… Will this new ECB scheme also fail? As long as central bankers (and politicians) continue to push for schemes and policies without properly understanding their effects on banks’ internal ‘mechanics’, they will be doomed to fail.

PS: I have been busy recently so few updates. I have a number of posts in the pipeline… I just need to find the time to write them!

One year of blogging

Here we go; this blog was created exactly a year ago. This whole year, I have tried to defend and justify laissez-faire policies in banking and finance. This blog, as well as all the debates to which I have participated through it, have required me to question, or even revise, my views on banking and economics. I was forced to read and think about certain topics much more in depth that I would ever have done without it. My worldview and my knowledge have evolved.

I wish to thank all followers and guests, as well as all people who provided me with information and even those who have challenged me. Not only your views and comments persuaded me to continue, but you also made me a better person.

There is still a lot of work to do though. And I will continue to defend a classical liberal point of view in finance for the foreseeable future. Please don’t forget to share!

Here are some of the major series of posts that have defined this year of blogging:

Stable rules, macro-prudential policies and regulatory uncertainty (plenty of other posts build on those ones):

- Macro(un)prudential regulation

- The case for stable rules

- A few complementary notes on regime uncertainty

Bagehot’s writings:

- BoE’s Mark Carney is burying Walter Bagehot a second time

- What Walter Bagehot really said in Lombard Street (and it’s not nice for central bankers and regulators)

The RWA-based Austrian business cycle theory (the distortive effects of RWAs is a recurrent theme):

- Banks’ risk-weighted assets as a source of malinvestments, booms and busts

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Update

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – A graphical experiment

- Banks’ RWAs as a source of malinvestments – Some recent empirical evidence

- A new regulatory-driven housing bubble?

- Is the US dissociating from Basel banking rules?

- A tale of two US lending curves

- Basel vs. ECB’s TLTRO: The fight

- Sovereign debt crisis: another Basel creature?

- New research at last asks the right questions on RWAs

The endogenous money and MMT banking theory debates:

- The problems with the MMT-derived banking theory

- A response to Scott Fullwiler on MMT banking theory

- The central bank funding stigma

- Banks don’t lend out reserves. Or do they?

- The BoE says that money is endo, exo… or something

- Tobin vs. Yeager, my view

- More inside/outside money endogeneity confusion

Does the central bank control interest rates and implications:

- Mortgage rates are still determined by the BoE

- A clarification on mortgage rates for ASI’s Ben Southwood

- Is the zero lower bound actually a ‘2%-lower bound’?

- Could P2P Lending help monetary policy break through the ‘2%-lower bound’?

The importance of banks’ intragroup funding and free liquidity and capital flows:

- Balkanise or globalise banking, there is no middle way

- Is regulation killing banking… for nothing? The importance of intragroup funding

- The importance of intragroup funding – The 19th century US experience

- The importance of intragroup funding – 19th century US vs. modern Germany

- The importance of intragroup funding – 19th century Canada

Book reviews:

- Felix Martin and the credit theory of money

- Calomiris and Haber are pretty much spot on

- A brief comment on Piketty

- A couple of comments on ‘House of Debt’

Guest posts:

- Endogenous Money vs. the Money Multiplier (guest post by Justin Merrill)

- Greenspan put, Draghi call? (guest post by Vaidas Urba)

- Macroprudential policy tools: a primer (guest post by Justin Merrill)

And of course, plenty of other, more independent, posts (about financial history misinterpretation, financial innovation, central bankers as new central planners, etc.).

Two kinds of financial innovation

Paul Volcker famously said that the only meaningful financial innovation of the past decades was the ATM. Not only do I believe that his comment was strongly misguided, but he also seemed to misunderstand the very essence of innovation in the financial services sector.

Financial innovations are essentially driven by:

- Technological shocks: new technologies (information-based mostly) allow banks to adapt existing financial products and risk management techniques to new technological paradigms. Without tech shocks, innovations in banking and finance are relatively slow to appear.

- Regulatory arbitrage: financiers develop financial products and techniques that bypass or use loopholes in existing regulations. Some of those regulatory-driven innovations also benefit from the appearance of new technological and theoretical paradigms. Those innovations are typically quick to appear.

I usually view regulatory-driven innovations as the ‘bad’ ones. Those are the ones that add extra layers of complexity and opacity to the financial system, hiding risks and misleading investors in the process.

It took a little while, but financial innovations are currently catching up with the IT revolution. Expect to change the way you make or receive payments or even invest in the near future.

See below some of the examples of financial innovation in recent news. Can you spot the one(s) that is(are) the most likely to lead to a crisis, and its underlying driver?

- Bank branches: I have several times written about this, but a new report by CACI and estimates by Deutsche Bank forecasted that between 50% and 75% of all UK branches will have disappeared over the next decade. Following the growing branch networks of the 19th and 20th centuries, which were seen as compulsory to develop a retail banking presence, this looks like a major step back. Except that this is actually now a good thing as the IT and mobile revolution is enabling such a restructuring of the banking sector. SNL lists 10,000 branches for the top 6 UK bank and 16,000 in Italy. Cutting half of that would sharply improve banks’ cost efficiency (it would, however, also be painful for banks’ employees). It is widely reported that banks’ branches use has plunged over the past three years due to the introduction of digital and mobile banking.

- In China, regulators have introduced new rules to try to make it harder for mainstream banks to deal with shadow banks in order to slow the growth of the Chinese shadow banking system, which has grown to USD4.9 trillion from almost nothing just a few years ago. The Economist reports that, by using a simple accounting trick, banks got around the new rules. Moreover, while Chinese regulators are attempting to constrain investments in so-called trust and asset management companies, investors and banks have now simply moved the new funds to new products in securities brokerage companies.

- In London, underground travellers can now pay for their journey by simply using their contactless bank card. No need of a specific underground card anymore. NFC-enabled smartphones will be able to do the same in the near future.

- Barclays is experimenting contactless wristband that would effectively replace your contactless card for payments (or, for Londoners, your underground Oyster Card).

- Apple announced Apple Pay, a contactless payment system managed by Apple through its new iPhones and Watch devices. Apple will store your bank card details and charge your account later on. This allows users to bypass banks’ contactless payments devices entirely. Vodafone also just released a similar IT wallet-contactless chip system (why not using the phone’s NFC system though? I don’t know. Perhaps they were also targeting customers that did not own NFC-enabled devices).

- Lending Club, the large US-based P2P lending firm, has announced its IPO. This is a signal that such firms are now becoming mainstream, as well as growing competitors to banks.

Of course, a lot more is going on in the financial innovation area at the moment, and I only highlighted the most recent news. Identifying the regulatory arbitrage-driven innovations will help us find out where the next crisis is most likely to appear.

PS: the growth of cashless IT wallets has interesting repercussions on banks’ liquidity management and ability to extend credit (endogenous inside money creation), by reducing the drain of physical cash on the whole banking system’s reserves (outside money). If African economies are any guide to the future (see below, from The Economist), cash will progressively disappear from circulation without governments even outlawing it.

Some finance artefacts

I am back from my trip in North America, which led me to New York, where I saw some interesting finance artefacts in various locations. Here is a sample (click to enlarge):

World War finance propaganda

The very first US Treasury warrant

Private bank notes

Great Depression local government currencies printed to alleviate the lack of Fed money

US Treasury notes redeemable in gold

Various old bond certificates

A share certificate owned by… Bernard Madoff

And the most curious of them all: a Disney-decorated US Treasury WW2 bond… Slightly strange mix

The mystery of collateral

Collateral has been the new fashionable area of finance and capital markets research over the past few years. Collateral and its associated transactions have been blamed for all the ills of the crisis, from runs on banks’ short-term wholesale funding to a scarcity of safe assets preventing an appropriate recovery. Some financial journalists have jumped on the bandwagon: everything is now seen through a ‘collateral lens’. The words ‘assets’, and, to a lesser extent ‘liquidity’ and ‘money’ themselves, have lost their meaning: all are now being replaced by ‘collateral’, or used interchangeably, by people who don’t seem to understand the differences.

A few researchers are the root cause. The work of Singh keeps referring to any sort of asset transfer between two parties as ‘collateral transfer’. This is wrong. Assets are assets. Securities are securities, a subset of assets. Collateral can be any type of assets, if designated and pledged as such to secure a lending or derivative transaction. Real estate, commodities and Treasuries can all be used as collateral. Money too. Unlike what Singh and his followers claim, a securities lender lends a security not a collateral. Whether or not this security is used as collateral in further transactions is an independent event.

This unfortunate vocabulary problem has led to perverse ramifications: all liquid assets, or, as they often say, collateral, are now seen as new forms of money (see chart below, from this paper). Specifically, collateral becomes “the money of the shadow banking system”. I believe this is incorrect. Collateral is used by shadow banks to get hold of money proper. Building on this line of reasoning, people like Pozsar assert that repo transactions are money… This makes even less sense. Repos simply are collateralised lending transactions. Nobody exchanges repos. The assets swapped through a repo (money and securities) could however be exchanged further. Depressingly, this view is taken increasingly seriously. As this recent post by Frances Coppola demonstrates, all assets seem now to be considered as money. This view is wrong in many ways, but I am ready to reconsider my position if ever Treasuries or RMBSs start being accepted as media of exchange at Walmart, or between Aston Martin and its suppliers. Others have completely misunderstood the differences between loan collateralisation and loan funding, which is at the heart of the issue: you don’t fund a loan, whether in the light or the dark side of the banking system, with collateral! The monetary base/high-powered money/cash/currency, is the only medium of settlement, the only asset that qualifies as a generally-accepted medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account (the traditional definition of money).

There is one exception though. Some particular transactions involve, not a non-money asset for money swap, but non-money asset for another non-money asset swap. This is almost a barter-like transaction, which does occur from time to time in securities lending activities (the lender lends a security for a given maturity, and the borrower pledges another security as collateral). Nonetheless, the accounting (including haircuts and interest calculations) in such circumstances is still being made through the use of market prices defined in terms of the monetary base.

Still, collateral seems to have some mysterious properties and Singh’s work offers some interesting insights into this peculiar world. The evolution of the collateral market might well have very deep effects on the economy. The facilitation of collateral use and rehypothecation, as well as the requirements to use them, either through specific regulatory and contractual frameworks, through the spread of new technology, new accounting rules or simply through the increased abundance of ‘safe assets’ (i.e. increased sovereign debt issuance), might well play a role in business cycles, via the interest rate channel. Indeed, by facilitating or requiring the use of increasingly abundant collateral, interest rates tend to fall. The concept of collateral velocity is in itself valuable: when velocity increases, interest rates tend to fall further as more transactions are executed on a secured basis. Still, are those transactions, and the resulting fall in interest rates, legitimate from an economic point of view? What are the possible effects on the generation of malinvestments?

An example: let’s imagine that a legal framework clarification or modification, and/or regulatory change, increases the use and velocity of safe collateral (government debt). New technological improvements also facilitate the accounting, transfer, and controlling processes of collateral. This increases the demand for government debt, which depresses its yield. Motivated by lower yield, the government indeed issues more debt that flow through financial markets. As the newly-enabled average velocity of collateral increases substantially, more leveraged secured transactions take place and at lower interest rates. While banks still have exogenous limits to credit expansion (as the monetary base is controlled by the central bank), the price of credit (i.e. endogenous money creation) has therefore decreased as a result of a mere regulatory/legal/technological change.

I have been wondering for a while whether or not such a change in the regulatory paradigm of collateral use could actually trigger an Austrian-type business cycle. I do not yet have an answer. Implications seem to be both economic and philosophical. What are the limits to property rights transfer? How would a fully laisse-faire market deal with collateral and react to such technological changes? Perhaps collateral has no real influence on business fluctuations after all. There is nevertheless merit in investigating further. I am likely to explore the collateral topic over the next few months.

PS: I will be travelling in North America over the next 10 days, so might not update this blog much.

* There are many many flaws in Frances’ piece. See this one:

But suppose that instead of a sterling bank account, a smartcard or a smartphone app enabled me to pay a bill in Euros directly from my holdings of UK gilts? This is not as unlikely as it sounds. It would actually be two transactions – a sale of gilts for sterling and a GBPEUR exchange. This pair of transactions in today’s liquid markets could be done instantaneously. I would in effect have paid for my meal with UK government debt.

She fails to see that she would have paid for her mean with Sterling, not with government debt! Government debt must be converted into currency as it is not a medium of exchange/settlement.

Breaking banks won’t help economic recovery

In contrast with the bank-bashing environment of the post-crisis period, voices are increasingly being raised to moderate regulatory, political and judiciary risks on the banking system.

Last week, Gillian Tett wrote an article in the FT tittled “Regulatory revenge risks scaring investors away”. She says:

Last month [Roger McCornick’s] project team published its second report on post-crisis penalties, which showed that by late 2013 the top 10 banks had paid an astonishing £100bn in fines since 2008, for misbehaviour such as money laundering, rate-rigging, sanctions-busting and mis-selling subprime mortgages and bonds during the credit bubble. Bank of America headed this league of shame: it had paid £39bn by the end of 2013 for its transgressions. When the 2014 data are compiled, the total penalties will probably have risen towards £200bn.

She argues that “legal risk is now replacing credit risk.” This is a key issue. Banks have already been hit hard by new regulatory requirements, which sometimes require a fundamental restructuring of their business model. The consequences of this framework shift is that profitability, and hence internal capital generation, remain subdued, weakening the system as a whole. Banks now reporting double digit RoEs are more the exceptions than the rule. Moreover, low profitability also reduces the banks’ ability to generate capital externally (i.e. capital raising) because they do not cover their cost of capital. This scares investors away, as they have access to better risk-adjusted investment opportunities elsewhere.

The enormous amounts raised through litigation procedures make such a situation even worse. Admittedly, banks that purposely bypassed laws or committed frauds should be punished. But, as The Economist argues this week in a series of articles called “The criminalisation of American business” (see follow-up article here), the “legal system has become an extortion racket”, whose “most destructive part of it all is the secrecy and opacity” as “the public never finds out the full facts of the case” and “since the cases never go to court, precedent is not established, so it is unclear what exactly is illegal”:

This undermines the predictability and clarity that serve as the foundations for the rule of law, and risks the prospect of a selective—and potentially corrupt—system of justice in which everybody is guilty of something and punishment is determined by political deals. America can hardly tut-tut at the way China’s justice system applies the law to companies in such an arbitrary manner when at times it seems almost as bad itself.

Estimates of capital shortfall at European banks vary between EUR84bn and as much as EUR300bn (another firm, PwC, estimates the shortfall at EUR280bn). Compare those amounts with the hundreds of billions Euros paid or about to be paid by banks as litigation settlements, and it is no surprise that banks have to deleverage to comply with regulatory capital ratio deadlines and upcoming stress tests… Such high amounts, if justified, could probably have been raised by prosecutors at a slower pace in the post-crisis period without endangering the economic recovery (banks’ balance sheets would have been more solid more quickly, which would have facilitated the lending channel of the monetary transmission mechanism).

In the end, regulatory regime uncertainty strikes banks twice: financial regulations keep changing (and new ones are designed), and opaque litigation risk is at an all-time high. Banks are now very risk-averse, depressing lending and international transactions. This seems to me to replicate some of the mistakes made by Roosevelt during the Great Depression. Despite all the central banks’ money injection programmes, this may not be the best way out of an economic crisis…

PS: Commenting on the forthcoming P2P lender Lending Club IPO, Matt Levine argues that:

But Lending Club can grow its balance sheet all it wants. Lending Club is not a bank. So it’s not subject to banking regulation, which means that it can do a core function of banking much more efficiently than an actual bank can.

He is (at least) partly right. By killing banks, regulatory constraints are likely to trigger the emergence of new types of lenders.

Wait… Isn’t it what’s already happened (MMF and other shadow banking entities…)?

A couple of comments on ‘House of Debt’

I just read House of Debt, the latest book by Mian and Sufi, which got a relatively wide coverage in the media, so I thought I should write a quick post about it.

Overall, it’s a good book, accessible for those who do not have a background in economics or finance. What I particularly liked about the book is its emphasis on leverage. The boom in household and business leverage over the past two decades inevitably fuelled an unsustainable boom in aggregate spending. Bringing indebtedness back to more ‘normal’ values also inevitably reduces spending power*. Yet, too many economists seem to take this pre-crisis trend as normal.

They are also right to advocate letting banks fail, as well as question the non-monetary banking intermediation channel (as proposed by Bernanke in his famous article Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression) and the effectiveness of monetary policy following a debt boom.

However, the authors never explain the underlying causes of the leverage boom and the crisis. It seems to be assumed that financial innovations (i.e. securitization mostly) appear all of a sudden, enabling an unsustainable boom to take place. What role did monetary policy play during the period? Or banking regulation? Those questions remain unanswered. Yet, as I’ve been explaining for now close to a year, the combination of those two factors was critical in triggering the boom in financial innovation, leverage, and malinvestments. I wish Mian and Sufi had provided their thoughts on that topic in their book.

They provide evidence that house prices increased the most in counties with inelastic housing supply. Still, they also strongly increased in those with elastic housing supply… They focus on the Asian ‘savings glut’, which would have flowed into the US. Perhaps, but it doesn’t mean that the Fed rate wasn’t too low, and many countries all around the world also experienced booming housing markets. Moreover, mortgage delinquencies started when the Fed increased its base rate… Despite being a US-centric book, there is also no discussion of the particular populist political framework at play in designing both the peculiar US banking system and the crisis, as described by Calomiris and Haber.

As a result, they seem to identify the rise in securitization as a fraud. I believe this is not the case. Banks started holding securitized assets on their balance sheet because of their beneficial capital treatment. There is little sign that they tried to originate bad assets to defraud naïve investors. Indeed, take a look at the chart below (from a recent post): banks also invested in such products and self-retained tranches of those they had originated throughout the boom period, and continue to do so. This points to ignorance of the risks. Not fraud.

I encourage you to read the book for its very good data gathering. Despite some of its (relatively minor) flaws, the book does much to debunk some myths through the appropriate use of empirical evidence.

* This doesn’t mean that there wasn’t also an excess demand for money at that time. Just that a decreased money supply through debt deflation exacerbated the problem.

Recent Comments